To the casual observer, the preparations underway at Cape Canaveral in Florida indicate nothing more than a routine launch of yet another spacecraft to the latest destination in the solar system.

But the mission, which is scheduled for takeoff on Christmas Eve, is a turning point in space exploration. Rather than running the program, Nasa hands over control: he paid a private company, Astrobotic, to design a spacecraft and handle its launch and landing.

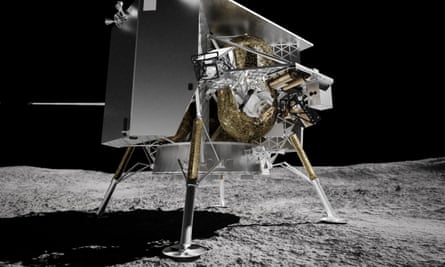

Save for the last minute, Peregrine Mission 1 – named after the fastest animal on Earth – will blast off at 6.50am UK time on a weeks-long journey to the moon. It will thunder into space on the maiden flight of the new Vulcan rocket to become the first American lander sent to the moon in more than half a century.

The mission is the first in a fleet of private spacecraft headed to the moon in the next few years. Under Nasa’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative, the agency funds companies to build spacecraft and deliver cargo – along with payloads from other paying organizations – to various sites on the lunar surface.

The arrangement is a way to transport equipment to the moon before astronauts return there later this decade. With that in mind, the Peregrine mission will carry five NASA payloads to measure radiation, surface and subsurface water, and the thin layer of lunar gas called the exosphere.

Among Peregrine’s 15 other payloads are Japan’s moon dream capsule, containing messages from more than 80,000 children, one bitcoin from the Seychelles, and cremated human remains, courtesy of Elysium Space’s lunar memorial.

But this new era of lunar missions has some scientists scrambling. Future landers aim to drill for ice and other materials, possibly iron and rare earths, that are of interest to mining companies.

And this is where the conflict lies. Although scientists are generally enthusiastic about the lunar armada, they have other plans for the moon’s surface. They want radio telescopes on the far side of the moon because they are shielded from Earth’s electromagnetic noise. They want infrared telescopes in lunar craters hidden from the sun’s hot rays. There are even hopes of building gravitational wave detectors on the moon’s surface.

“There are all these legitimate activities on the moon that are completely incompatible with each other,” said Richard Green, an astronomer at the University of Arizona. “Mining is completely incompatible with an undisturbed scientific site, and likewise, when you land and take off, it kicks up a lot of debris.”

In addition to building moon-based observatories, scientists want to study the pristine moon ice and other materials before they are disturbed or polluted. It may hold the secrets to how volatile and organic compounds reached Earth, and show how space radiation can drive reactions relevant to life.

The problem is that no one is coordinating plans. And as more landlubbers touch land, and more companies invest, it will become more difficult to implement a fair and reliable process through which all countries and all sectors can pursue their goals without confusing things for others.

At the end of November, Green chaired the International Astronomical Union’s first working group on astronomy from the moon. He contacts teams around the world to identify lunar sites of special scientific interest, where conditions seem ripe for future telescopes or gravitational wave detectors.

But even if scientists can agree on a list of lunar sites to be fenced off, there is no global, authoritative body that can consider requests and grant protection. “If you have no regulations, there’s nothing stopping a company from landing in the same crater where you build a detector and dig things up and create a lot of dust and vibration,” says Ian Crawford, professor of planetary science at Birkbeck , University of London. “That’s what’s missing.”

One idea is to designate some craters at the lunar south pole as Sites of Special Scientific Interest, to preserve them for research. Crawford is in favor of the move, advocating that the entire north pole of the moon be declared off-limits to everyone until the extent of pollution caused by operations in the south becomes clear.

As for who should make the decisions, there are several groups, Crawford said. The Committee for Space Research (Cospar) has established planetary protection policy and can cover activities on the moon. The International Space Exploration Coordination Group (Isecg) should also be involved. And Nasa’s Artemis agreements, which outline principles for civilian exploration and use of outer space, could be updated to address conflicting activities on the moon, although China and Russia are unlikely to sign on.

We don’t have much time, says Green. “This is the latest space race,” he said. “We are currently at the stage where people are still establishing their abilities. But once there are prototypes on the moon and people set foot again, things will move pretty quickly. There are big commercial interests.”