Tthe first thing visitors to Paragraf’s laboratory, in the Cambridgeshire town of Somersham, are shown is a thin disc made of synthetic sapphire with a piece of graphene stuck to it. It was the first graphene product the company made, and it quickly evolved into a small wafer of 64 tiny graphene devices arranged in a grid. Today, the company produces six-inch wafers containing 9,000 chips.

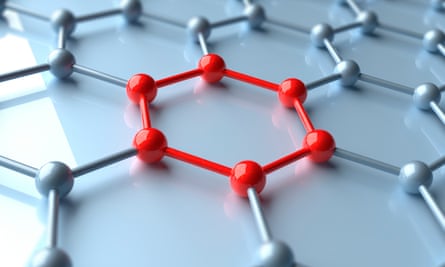

Graphene, a 2D form of carbon with the atoms arranged in a hexagonal structure, is mainly used to reinforce concrete and paint, but is now being touted as a replacement for silicon in semiconductors. China started using it to appear in the global microchip wars.

The UK must do everything it can to avoid China and the US losing out in the race to crack the technology, says Simon Thomas. He founded Paragraph in 2017 with Prof Sir Colin Humphreys and technical director Ivor Guiney, who all worked together at the University of Cambridge, as a university spinout.

Graphene, hailed as a “super material”, is extracted from graphite, the crystalline form of carbon used to make pencils, and comes as a lattice sheet just one atom thick. Thomas believes it will “fundamentally change the world” and will change the way everything from mobile phones and computers to electric cars, healthcare and military equipment is manufactured.

Smartphones made with the material can be worn on your wrist, and graphene tablets can be rolled up like a newspaper, according to the University of Manchester, where, in 2004, graphene was first produced.

Thomas, wearing a blue suit with matching shoes and a flowered shirt, says: “Graphene and other 2D materials will change the status quo to provide technology we’ve never seen before and levels of performance we’ve never seen before didn’t see In electronics, this will have a major effect on reducing energy consumption and creating faster semiconductors.”

Potential uses include quantum computing, magnetic sensors in a new generation of MRI scanners, and consumer technology such as delivery drones.

Graphene is one of the strongest and thinnest materials in existence, much tougher than steel but lighter than paper, harder than a diamond but more elastic than rubber. It is also highly effective at conducting heat and electricity.

Paragraph is one of the first companies in the world to mass-produce graphene-based devices, including sensors for electric cars.

In his Somersham lab, two reactors – large boxes whose main part is shaped like a pizza oven – produce enough graphene to make 150,000 sensors a day. Paragraph uses the material in two ways: to measure magnetic fields, and to convert microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses into electrical signals by combining graphene with a wet layer of chemistry as a biosensor.

Paragraph has thrown its weight behind biosensors, which can detect the difference between viral and bacterial infections to determine whether a person needs antibiotics. It can also reveal the presence of conditions such as Covid-19, or detect infectious diseases in plants or animals.

To expand its capacity in this area, Paragraph acquired a biosensor firm, San Diego’s Cardea Bio, in April. The devices will be manufactured at a new site a few kilometers away in Huntingdon.

Thomas spent 11 years working on semiconductors and composite materials for the German engineering company Aixtron, including spells in Asia. When he returned to the UK in 2015, Humphreys asked if they could work together, creating graphene on a larger scale.

Things could easily have been very different. Thomas was interested in science from an early age, but he also loved drawing and painting. He considered doing a degree in fine art, but a teacher advised against it, and he did aeronautical engineering at the University of Liverpool instead.

Thomas calls his background “working class”: his father was a colored patient in a factory, his mother a teaching assistant. “We didn’t have that many, but in the back of the dictionary they had was a periodic table,” Thomas remembers. He knew most of the table of chemical elements by heart by the age of six.

At Liverpool, Thomas went on to do a PhD in materials engineering.

More than a decade later, he joined Humphreys’ research team at Cambridge University, and later they set up Paragraph: the name is short for Paradigm Graphene.

The firm has attracted around £70m in funding so far and plans to list on the stock market in the next four or five years. “I would absolutely love to grow a manufacturing company here, grow it into a profitable business and list in the UK,” says Thomas, although he does not rule out a Nasdaq listing.

Investors include the British Treasury and In-Q-Tel, a venture capital firm linked to the CIA, which will help Paragraph expand in the US. Among his early supporters were Hermann Hauser, which helped set up the Cambridge chip designer Arm. His investment firm Amadeus Capital Partners holds a 6.7% stake in Paragraph.

Paragraph made a pre-tax loss of £11m in 2022, following a loss of £6.4m the year before, as an increase in staff and material costs fueled an almost sevenfold rise in revenue to almost £230,000 exceeded

Such growth attracted takeover interest from China, but Thomas and the board rejected the approaches, which would have required moving into the country. “It was a very attractive offer,” he says. “The problem with taking money out of China is that it doesn’t come without government interference.”

China has tried to corner the market in graphene. An estimated 5,000 companies are now working on graphene products there, says Ron Mertens, owner of the website Graphene-Info.

Chinese manufacturer Huawei uses graphene in its Pocket S clamshell phone, and Apple is reportedly testing graphene films for the iPhone 16 to prevent overheating.

A few months ago, China even declared that it would mass-produce microchips using graphene instead of silicon, making a complete transition by 2025, although the claim was met with skepticism in the west.

Thomas is encouraged by the Asian country’s ambition: “They have already seen the light. They saw the fact that this material is going to be a big future material, and they are committed.”

However, many graphene companies struggle to generate revenue and raise funding, and some have gone under. One of the first specialists, Applied Graphene Materials in Durham, sold its main business to a Canadian firm and liquidated the rest. Versarin in Gloucestershire has downsized its research team to cut costs.

In May the government announced a £1bn investment in the British semiconductor industry over the next decade, an amount dwarfed by the $52 billion spent by the US.

“If we want to be at the forefront, we have to have the support,” says Thomas. “Cash is always good, but it means commitments from the government to help us thrive in the UK. Commitments about how they will help us get talent, how they will help us put in infrastructure, and how they will help us trade with other countries.”

CV

Age 46

Family Single.

Education MEng in aerospace engineering, and PhD in materials science and engineering, from the University of Liverpool.

Last holiday Tenerife.

Best advice he was given “Always stand up for what’s right and what you believe in, even if you’re standing alone.”

Biggest career mistake”Getting too comfortable in a job and realizing that I should have moved on many years ago.”

Word he overuses”Integrable – not even a real word, but so important to get new materials into the semiconductor world.”

How he relaxes “When possible, run and sleep.”