He is known for discovering elements of the periodic table, for the invention of a lamp in 1815 which would save the lives of hundreds of thousands of miners and as an electrochemical pioneer.

But it is the unpublished poetry of the British chemist Sir Humphry Davy – and the intriguing connections between his poems and scientific breakthroughs – that are now electrifying academics.

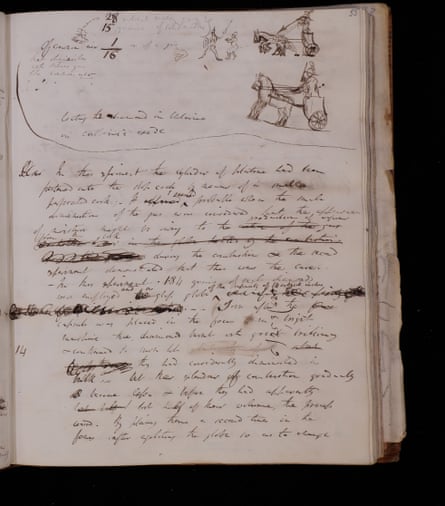

Researchers at Lancaster University have discovered that Davy secretly wrote down hundreds of poems in the same notebooks he used to record his ground-breaking electrochemical experiments, discoveries and revelations.

Almost all of these poems – including the one that appeared on Sunday in the Observer for the first time – has never been read before and offers fascinating insights into the inner workings of one of the most extraordinary scientific minds of the 19th century.

“The poetry is just everywhere,” says Sharon Ruston, an English professor at Lancaster University, who, with the help of nine other academics and nearly 3,500 volunteers worldwide, has spent the past four years sorting through 11,417 pages of Davy’s many 200 -year- old notebooks.

“You get a real sense of the man himself and his thought processes as he works through things.”

A friend of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the poet laureate Robert Southey, Davy was born, Ruston said, “before we had the idea that there was a dividing line between the arts and sciences”, and has only a few poems in his published lifetime, because he was praised by his famous friends.

But the notebooks reveal that his devotion to his craft was so strong that poems “sometimes drift into space, with stories of chemical discoveries”, and are found on “pages where you can see, from the condition of the page, that he is doing chemical experiments”.

These pages, which are torn, burnt or have “several stains on them from what he was wearing”, suggest that Davy wrote poems even in his laboratory, where he pioneered the field of electrolysis.

Ruston said, “He writes over nitrogen oxide or galvanism. But then there are also poems. These two things happen to him simultaneously. He tries to find out what the world is and how to understand the world.”

One of the most exciting finds is a poem written by Davy about the ruins he saw in Greece and Rome while on a continental tour between 1813 and 1815, which is interspersed with scientific notes about the material found in the ruins. and sculptures were used.

“This tour is quite an important moment in Davy’s life,” said Ruston.

It was during this tour of Europe with his protégé Michael Faraday, who would go on to invent the first electric generator, that Davy proved the elemental nature of iodine and that diamonds are made of carbon.

She said: “It blew their minds because you start to realize that one substance can take many different forms. So Davy has this real worldview, that there is nothing in the world that can be created or destroyed. All the matter we have is all around us, but it is constantly changing, very slowly, into new forms.” Ruston sees a “symbiotic relationship” between Davy’s science and his poetry. “They work with each other.”

For example, he would write about the chemical reasons why leaves change color and then a few pages later compose a poem about the color of leaves. He thought and wrote about his ideas, Ruston said, “in both ways: poetry and science. And in his poetry you can see his scientific knowledge, and in his science you can see poetic language and persuasive rhetoric, and his facility to express himself.”

Mark Miodownik, professor of materials and society at University College London, said the discovery of Davy’s poems was significant because it demonstrated that “you can’t be a great scientist and you can’t be a creative person. The idea that the creative industries are exclusively for the arts and humanities is a modern fallacy.”

Poetry was a private part of Davy’s creative process. “I think he couldn’t help himself. He’s so full of wonder and awe that he had to do that — things were going around in his head and he had to get them out,” Miodownik said.

The notebooks also contain doodle-like sketches of landscapes and faces, and notes about buying candlesticks and other everyday matters. “We have the pages where he actually isolates potassium with electrolysis. But in the middle of it, he mentioned this person and their address,” Ruston said.

Her team discovered it was a reference to a tailor. “We think he’s been thinking about how he’s going to announce his amazing discovery at the Royal Society and he’ll need a new suit to do that,” she said.

One of the poems found in Davy’s notebooks, published for the first time

You great memorials of the fate of man;

This is a moral lesson for our eyes

Stronger and more impressive than the leather

Which envelops the wiser learning and heavy tomes.

to newsletter promotion

To erect a temple and satisfy

Imperial pride and luxury. The world

Was ruined as a million slaves were taught to lift the pole

Suitable for barbaric sports. In which the blood

Some of the man was dumped. The master of the world

The image of eternal majesty

Torn by the fangs of the relentless beast

The rack was brought from Egypt.

Ancient Greece was robbed of all her gods

Her temples are spoiled.

And the deities that Phidias fashioned

Was brought to the capital in slavery

What remains now, pillars & broken shafts

A pile of ruins. Witness those massive walls

Where once a hundred thousand votes were cast

The Dying Gladiator; silence reigns

And terrible loneliness – yet a spirit dwells

Within these ruins.