A super hurricane is brewing in the Atlantic Ocean in the opening pages of The displacements, a novel by Bruce Holsinger published in 2022. “This is the one climatologists have been warning us about for twenty years,” one character declares. Forty pages in, the so-called Hurricane Luna takes a surprising turn for Miami and ends up pummeling South Florida with a wall of water, toppling skyscrapers, leveling wastewater plants, and filling the Everglades with contaminated silt. With 215 mph winds, faster than a violent tornado, the fictional Luna is the world’s first Category 6 hurricane.

In the real world, Category 5 is synonymous with the biggest and worst storms. But some American scientists make the case that it no longer captures the intensity of recent hurricanes. A paper published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences lays out a framework for expanding the current hurricane rating system, the Saffir-Simpson scale, with a new category for storms packing winds of 192 miles per hour. hour has According to the study, the world has already seen storms that would qualify as Category 6s.

“We expected that climate change would make the winds of the most intense storms stronger,” said Michael Wehner, a co-author of the paper and an extreme weather researcher at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “What we have demonstrated here is that, yes, it is already happening. We tried to give figures on how much worse it will get.”

There is a reason why books last The displacements appeal Category 6: It grabs your attention, warning of a threat that is like nothing you’ve ever encountered. The concept could help the public grapple with the dangers of climate change, such as more intense storms. But some experts aren’t convinced that incorporating “Category 6” into our hurricane vocabulary will be helpful.

What storms would count as a category 6?

The idea of adding a category 6 has popped up various times in the last few decades, while storms such as Hurricane Dorian in 2019 produced some of the highest wind speeds on record (185 miles per hour) and whole villages flattened in the Bahamas. The current Category 5 designation refers to any tropical cyclone with wind speeds greater than 157 miles per hour.

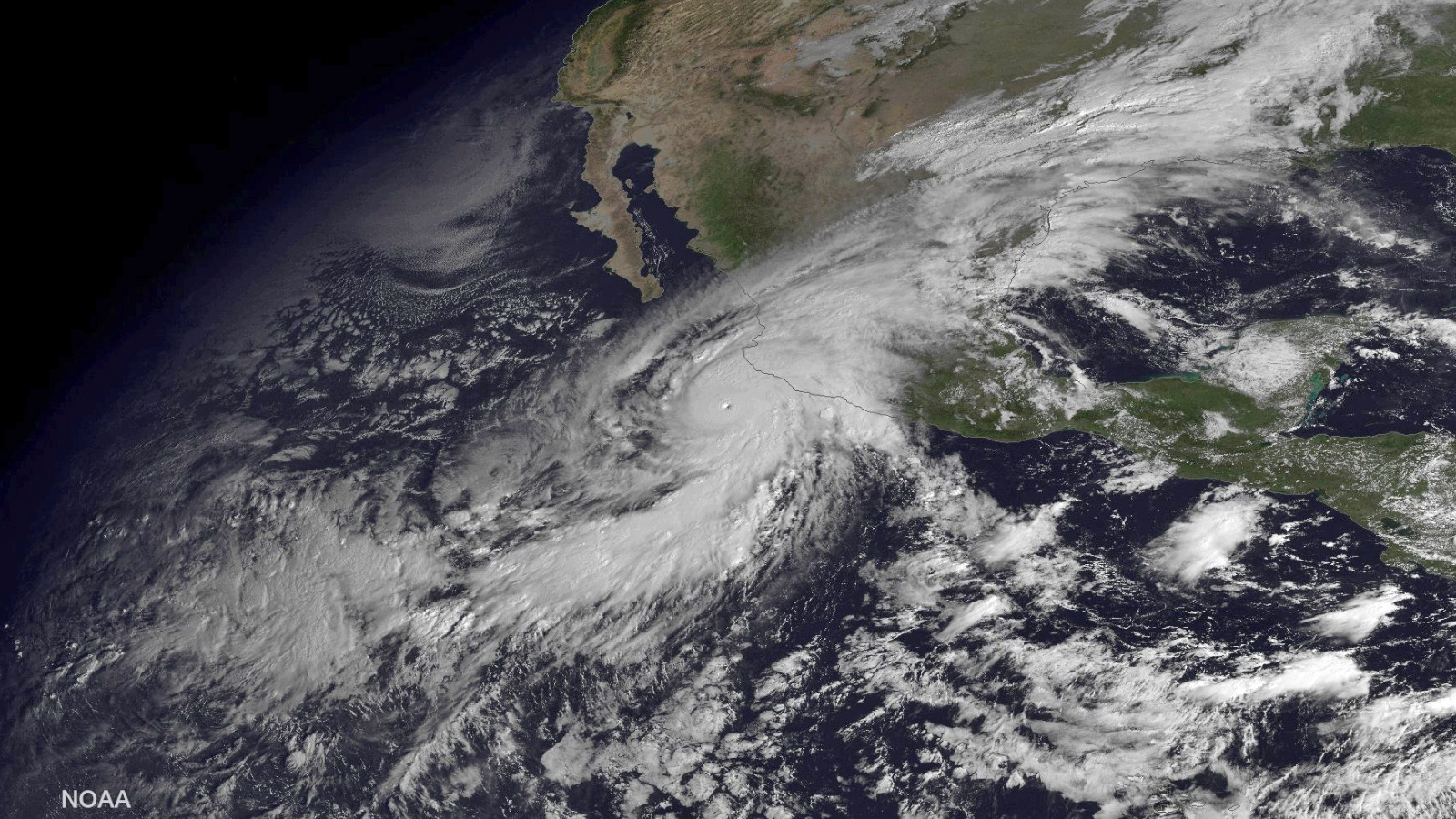

The new threshold of 192 mph for a Category 6 would have captured some of the strongest storms ever observed. Wehner and his co-author James Kossin, a scientist at the climate nonprofit First Street Foundation, found that at least five storms have already reached this level, and that they all occurred in the past decade, a sign that a warm world more monster creates storms. The most powerful of these storms, Hurricane Patricia, slammed into Mexico’s Pacific coast in 2015 with winds that peaked at 215 miles per hour. By good luck, the storm hit a relatively unpopulated region and caused only six deaths. When another of the most powerful storms, Typhoon Haiyan, hit the Philippines in 2013 with winds of 195 miles per hour, it killed more than 6,000 people, making it one of the deadliest disasters in modern history.

The Gulf of Mexico has not seen a storm with such strong winds in the modern era, but the authors found that conditions in the region are already ripe for a Category 6. That’s because climate change is warming the ocean and atmosphere , which provides for fuel for more intense hurricanes. Undertaking an analysis of atmospheric conditions in the Atlantic Ocean, Wehner and Kossin found that there were several occasions when the Gulf was warm enough to support a storm with winds in excess of 190 miles per hour—that’s just ‘ A dumb luck that one t still happened. As the world warms, the chances of us seeing such a storm increase: The authors find that 2 degrees Celsius of warming would increase the risk of a Category 6 storm forming in the Atlantic in any given year triple.

The pitfalls of adding a new category

It is becoming clear that flooding is the deadliest aspect of a hurricane. Storm surges account for about half of deaths from hurricanes in the United States, and flooding from heavy rain accounts for more than a quarter, according to the study. By contrast, high winds are behind just 8 percent of deaths. Since the Saffir-Simpson scale is based solely on the speed of their winds, it doesn’t communicate the risks people should be most concerned about, but it’s the most important thing people usually know about an approaching storm.

“The bottom line is that adding a Category 6 just reinforces the miscommunication of the greatest hurricane risks,” said Marshall Shepherd, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Georgia.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

The public is already confused by the jargon in hurricane forecasts, such as the “cone of uncertainty” showing a storm’s projected path, or the difference between a “watch” and a “warning.” Shepherd believes adding a new category could make it worse.

“You know, people are habits,” he said. “They have been conditioned to believe that Cat 5 is the strongest hurricane. “OK, now, well, what are the categories?” For me, it creates a lot more communication inconsistencies and confusion for the public.”

People often base their evacuation decisions on a storm’s Saffir-Simpson category, according to Jennifer Collins, a professor of geoscience at the University of South Florida. When Hurricane Florence was downgraded from a Category 4 to a Category 1 before landfall in the Carolinas in 2018, people who evacuated actually turned around and came back and experienced severe flooding as a result, Collins said.

“When they hear Category 5, I think people will respond to that,” Collins said. “It’s really when we use those lower categories that people don’t respond when they should.” National Hurricane Center experts have said in the past that adding a new category will not do much good, as a Category 5 is already considered catastrophic. Since the National Hurricane Center is in charge of the Saffir-Simpson scale, Category 6 will not happen unless those experts are convinced it is necessary.

The authors of the new paper do not think that expanding the category system would solve these hurricane communication problems. “We’re not trying to address these other inadequacies,” Wehner said. “We’re trying to raise awareness that climate change is increasing the risk of intense storms, and not just category 6, but category 4 and 5 as well.”

While it’s hard to predict exactly how people will react to a Category 6 storm, Jennifer Marlon, a research scientist at the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, thinks the designation will be helpful. “This will send a clear signal to coastal residents that your past experience with storms is not a good measure of future impact,” Marlon said in an email. “Storms are no longer ‘all natural’, and they are getting stronger.”

A better way to communicate hurricane risks?

These days, when a hurricane heads ashore, Shepherd doesn’t talk much about his category at all. Instead, he focuses on explaining threats from storm surges and flooding, sharing visuals that show the risks.

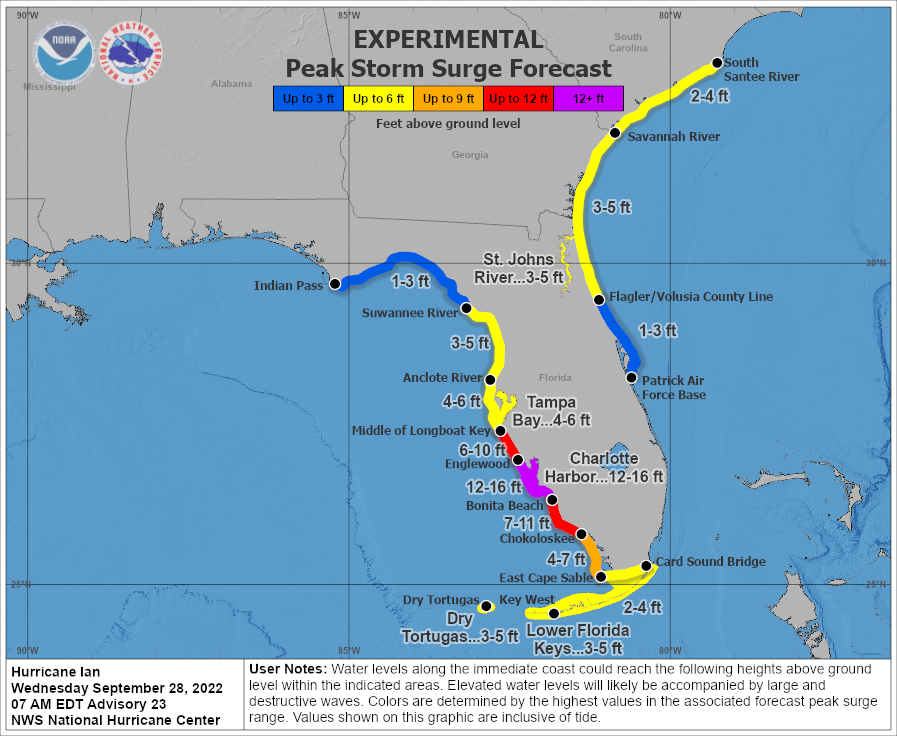

Over the past decade, the National Hurricane Center has experimented new storm surge maps highlighting the risk of inland flooding rather than the wind speed of a storm. In the run-up to hurricanes like Ian in 2022, for example, the agency new maps published every few hours which showed how many feet of flooding would hit each segment of the coast. These maps are simple and easy to understand, and they have become a more central part of the NHC’s efforts to communicate storm risk in recent years.

“We’ve probably entered a new generation of hurricanes, in terms of intensity and rapid intensification,” Shepherd said. “I don’t want to play it down or play it down because it is critical. So instead of worrying about characterizing a new category, my broader message is, ‘OK, what are we going to do, from an adaptation and a resilience standpoint, about this new generation of hurricanes?’