Naomi Davis will not lose her faith in the earth. At a recent community meeting on Chicago’s South Side, she wanted to drive home the point — that the city’s Black community will not be left out of the new, emerging green economy.

To do this, she is betting on energy trapped deep below the earth’s surface, known as geothermal, which could be an answer to heating and cooling homes more efficiently and a path to building decarbonisation.

Davis heads Chicago Blacks in Greenan environmental justice group that has devoted the past 17 years to figuring out the blueprint for self-sustaining, climate-resilient black communities everywhere.

“We get hit first and worst, the least and last, and we contribute the least to global warming,” Davis said.

David McDuffie

Last year, the group won the support of the Biden administration with the Environmental Protection Agency granting a five-year $10 million grant. The money will enable Blacks in Green to work with other environmental justice communities in the Midwest to take advantage of historic funding made available by the Inflation Reduction Act.

The Chicago organization is already starting to work on sustainability projects Cleveland.

At home, Davis is focused on carbon-free energy: how to generate it, how to make it affordable and how to get it out of the ground. Her goal is to ensure that her community is not left behind as the rest of the city becomes sustainable.

“We’re not going to be the ones left on the gas bills with the rising costs and the technology that continues to pollute us,” she said, adding for emphasis, “No.”

In 2023, Blacks in Green was one of 11 community partners across the country selected by the US Department of Energy to design and develop a common geothermal heating and cooling district. That would mean building out a shared geothermal network across four city blocks containing more than 100 multi-family and single-family homes.

The aim is to decarbonise buildings and reduce energy costs for families. To get there, Blacks in Green almost received $750,000 to kick off the initial phase of the pilot, which includes hosting community meetings and determining household needs.

Davis said Chicago’s West Woodlawn neighborhood — located about 9 miles south of the city’s downtown — is poised to experiment with geothermal energy.

But at the Blacks in Green community meeting, neighbors like Debra Gay and her mother Retta Ford have questions about what exactly it will take to bring geothermal energy to the South Side.

“Given that our city lots are so closely spaced, how would you do that for an existing house and would it cause some disruption?” asked Gay.

Ford, Gay’s mother, was concerned that the project could destabilize the foundations of older homes.

Not necessarily, according to Andrew Barbeau, president of the Accelerate Group, a clean energy consulting firm working with Blacks in Green to design and deploy the geothermal pilot project.

The key to geothermal in these old neighborhoods: the alleys.

“Up front you have water, you have gas, you have sewer, and other things are alleys,” Barbeau said. “There is nothing under that soil.”

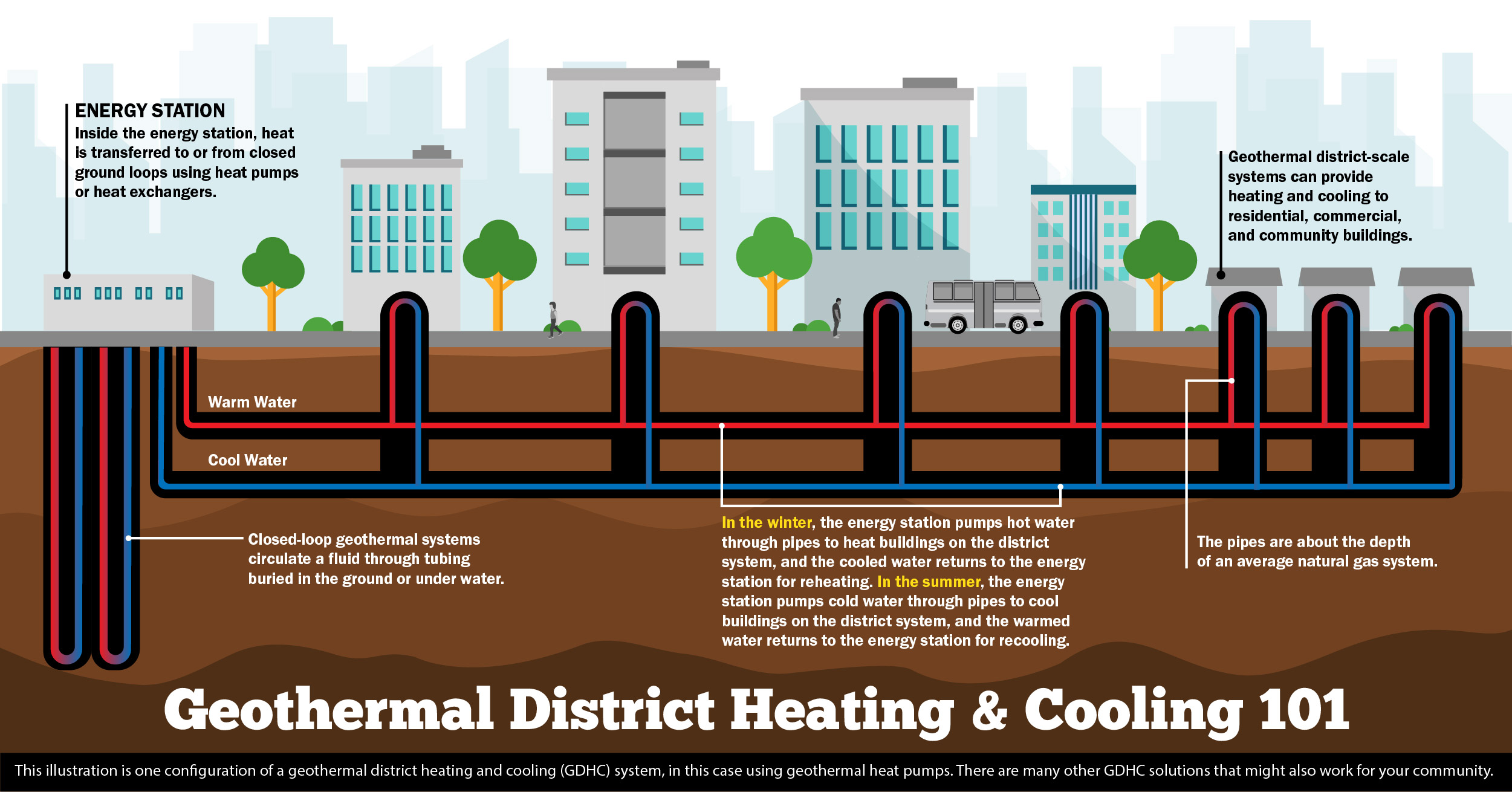

The plan is to utilize the earth under the alleys behind homes and businesses to build out a communal geothermal system. This would mean a series of 400-foot deep holes that would pipe water into the ground, absorb the temperature of the earth, and bring it back to the surface for use.

By building the community heating system under the alleys, the project sidesteps the major challenge facing large American cities like Chicago: lack of open, workable space. Once installed, buildings along the alley can connect to the underground heating system at their own convenience.

This all works because the earth functions as a kind of thermal battery. The sun strikes the earth, and it absorbs some of that energy. So much so that between 20 and 40 feet below the surface of the earth, the temperature consistently hovers around 12.8 degrees C (55 degrees F) year-round, according to Andrew Stumpf, a geologist at the Prairie Research Institute at the University of Illinois Urbana -Campaign.

“So you circulate water in a pipe, and you exchange the heat from the pipe into the water, and you extract that temperature,” Stumpf said.

Experts call geothermal energy an almost inexhaustible source of energy, and it’s not limited to just Chicago. It can be brought online almost anywhere. Back in 2019, the DOE issued a study charting the path to massive scale geothermal across the country. It found significant economic opportunities for geothermal district systems throughout the Midwest and Northeast, with Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, New York and Pennsylvania leading the pack.

With 23 geothermal districts across the country, the US lags behind Europe, where nearly 400 is in effect.

While the DOE is investing in geothermal districts that rely on Earth’s near-surface temperatures, they’re also betting big on a larger scale improved geothermal systems, which usually requires miles of underground drilling. Improved geothermal works by pumping fluid deep into the earth, which is then recovered as steam and put to work to generate electricity.

Earlier this month, the Biden administration announced $60 million for three enhanced geothermal system pilots in California, Oregon and Utah. A DOE analysis last year found that by promoting improved geothermal energy, the US could be on track to generate 90 gigawatts electricity, or enough to power 65 million homes by 2050.

Geothermal in West Woodlawn is a long way out. Once the community engagement phase is completed, Blacks in Green will have the opportunity to be selected for up to $4 million in grants to actually go out and build the system.

But big questions remain. Who owns the geothermal network? Who decides the rates? West Woodlawn could develop public benefit corporations or local cooperatives that share benefits with residents.

The hope is not only to break ground in geothermal, but to explore new ownership models that center equity along the way.

Back at the Blacks in Green meeting, resident Rosazlia Grillier said she thinks a lot about what people sacrifice when they can’t pay their energy bills. She said the more people know about geothermal sources, the more likely they will be on board.

“Prices around energy costs are skyrocketing,” Grillier said. “And so we can either just complain about it, or we can educate ourselves about it and make the change that we know needs to happen.”