The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – the federal agency that monitors disease and establishes guidelines to protect human health – published a paper last month showing that cases of Lyme disease jumped nearly 70 percent nationwide in 2022. But what looked like an alarming increase in disease was actually the result of smarter disease surveillance that better reflects what’s happening on the ground.

The CDC revised its Lyme reporting requirements in 2022, making it easier for states with high infection rates to report those cases. The report, the first published analysis of the new data collection guidelines, shows the critical role that effective surveillance plays in better understanding the scope of infectious disease in the U.S. — and what more needs to be done to protect public health, as climate change the spread of ticks.

“Disease surveillance that is interpretable and standardized is integral to being able to understand how disease frequency is changing, and whether it is changing,” said Kiersten Kugeler, a CDC epidemiologist and lead author of the paper. She noted that climate change will complicate the already difficult task of monitoring and controlling diseases like Lyme. Cases in some areas will continue to rise while declining in others as parts of the US become more susceptible, or hostile, to ticks. “It’s not going to be straightforward,” Kugeler said. “It’s going to be incredibly important to have good surveillance to be able to understand how climate affects the risk of disease.”

Studies have significant shifts documented in Lyme trends across the country. The disease is caused by the bite of a black-legged tick and causes symptoms that range from flu-like and mild to neurological and debilitating, depending on how quickly the disease is diagnosed. Incidents doubled in the three decades between 1990 and 2020. Many researchers, including CDC employees, say climate change is one factor behind that sharp rise. Environmental changes such as urban sprawl and swelling populations of white-tailed deer, among other drivers, also play a role.

Warmer winter temperatures have attracted black-legged ticks to areas historically too harsh for the blood-sucking arachnids. Meanwhile, milder spring and fall seasons have given the pests more time to breed. Lyme is a sign of climate driven diseases to come. But as it spread to new areas and infected more people, the CDC struggled to capture the full impact.

In 2022, the agency redoubled its disease surveillance efforts, with a special emphasis on vector-borne diseases. As part of that push, the CDC relaxed its Lyme disease reporting requirements in the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic and Upper Midwest, where cases are high. Public health departments in those areas no longer have to track the clinical details of each positive Lyme test, such as a patient’s symptoms and when they started, and doctors can skip the labor-intensive process of recording and reporting them . Now a positive laboratory test is sufficient. Eliminating these steps takes the burden off doctors and local public health authorities and places it on state health departments, which are typically better equipped to handle them.

“We have a lot of behind-the-scenes data management that is new with this Lyme disease surveillance system,” Rebecca Osborn, a vector-borne disease epidemiologist at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. But overall, she said, “it’s gotten a little less bothersome.”

The new system risks including information about people who no longer show symptoms but still test positive for the bacteria, which can remain in the blood for years after the infection has cleared. But those cases likely comprise a small fraction of the overall data, the CDC said. In areas where Lyme remains rare, providers must continue to report clinical information for each case.

These relatively modest changes to the case definition requirements unearthed 62,551 cases of Lyme nationwide. This is 1.7 times the annual average reported from 2017 to 2019.

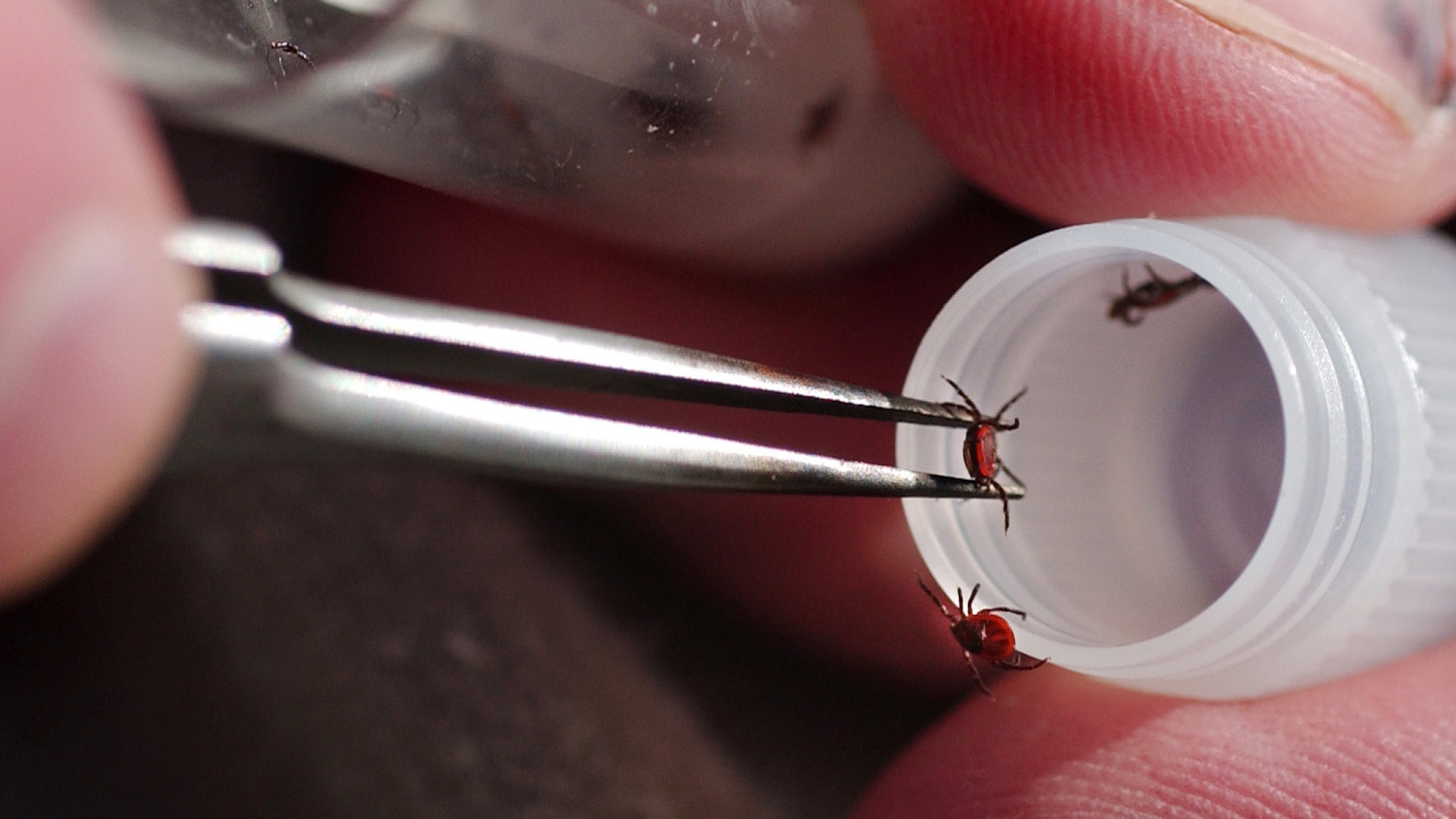

John Ewing/Portland Press Herald/Getty Images

Yet most cases of Lyme disease in the US go unreported. Studies based on health insurance records estimates that approximately 500,000 cases are diagnosed each year. Those reported by states to the CDC in 2022 accounted for less than one-fifth of that. Elizabeth Schiffman, an epidemiologist with the Vector Borne Diseases Unit at the Minnesota Department of Health, said figuring out how to catch every case is nearly impossible and perhaps beside the point.

“No system is ever perfect,” she said, “we’re always going to miss something, we’re always going to count something that probably shouldn’t be counted.” If the CDC can use the data it collects each year under its new system to measure the overall impact of Lyme, Schiffman said, then the number of cases it already knows about may be enough.

“If what we can capture can give us an idea of where things are happening, how things are changing, and inform good public health actions, it could be argued that we don’t need to count every case.”

The data shortage and lack of standardization among states becomes more of a problem when researchers try to pinpoint the impact of climate change on the disease. The CDC argues that in regions where Lyme incidence is still relatively rare, the updated surveillance system does not make sense. Doctors and local health departments in those areas still need to collect clinical information about every potential Lyme patient, because each case is a revealing data point rather than a statistic in a larger trend. But the onerous requirements in low-incidence areas are muddying efforts to trace the role of climate change in how black-legged ticks can migrate, said Richard Ostfeld, a senior scientist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies who researches tick-borne diseases.

The incidence of Lyme disease typically falls along geographic lines. States in the upper Midwest and Northeast report tens of thousands of cases each year, while those in the Southeast and South report hundreds. Although the CDC’s revised reporting guidelines more accurately revealed the extent of Lyme disease in high-incidence areas, implementing the system over time may mask growth of the disease elsewhere. The new guidelines “will tend to bias your estimate of geographic trends toward more growth in incidence in northern parts of the country, as opposed to southern parts of the country where you’re still very conservative,” Ostfeld said. “This complicates matters for those trying to understand the role of climate change.”

North Carolina, for example, a state long classified as low-incidence, was among five states with the highest number of Lyme disease-related insurance claims in 2016, according to one analysis. But the disease reporting there, says Noah Johnston, director of the Lyme awareness group Project Lyme, is still not where it needs to be. “There is an expectation that the tick populations in North Carolina are not as high as in the Northeast,” he said.

The advantages and disadvantages of the CDC’s updated surveillance highlight the difficulties of detecting and controlling infectious diseases under climate conditions that rapidly shift the distribution of disease vectors. Incremental adjustments to the status quo may not be enough to keep pace with the growing magnitude of disease risk. “We’re probably going to see more and more cases of these diseases and more and more diseases that are going to affect not only our population in the U.S., but globally,” Osborn said. “Public health in general needs to become a little more proactive in our responses. We’re still working on that as a field.”