It’s almost that magical time of year that the Humane Society of America likens to a “natural disaster.” Kitten season.

“The level of emotions for months on end is so exhausting,” said Ann Dunn, director of Oakland Animal Services, a city-run shelter in the San Francisco Bay Area. “And every year we just know it’s going to get harder.”

Across the United States, summer is the height of “kitten season,” typically defined as the warm weather months between spring and fall during which the cat becomes most fertile. For more than a decade, animal shelters across the country have noticed kitten season starting earlier and lasting longer. Some experts say the effects of climate change, such as milder winters and an earlier start to springcan blame for the increase in cat birth rates.

This past February, Dunn’s shelter held a clinic to spay and neuter outdoor cats. Although kitten season in Northern California doesn’t usually start until May, organizers found that more than half of the female cats were already pregnant. “It’s scary,” Dunn said. “It just gets earlier and goes later.”

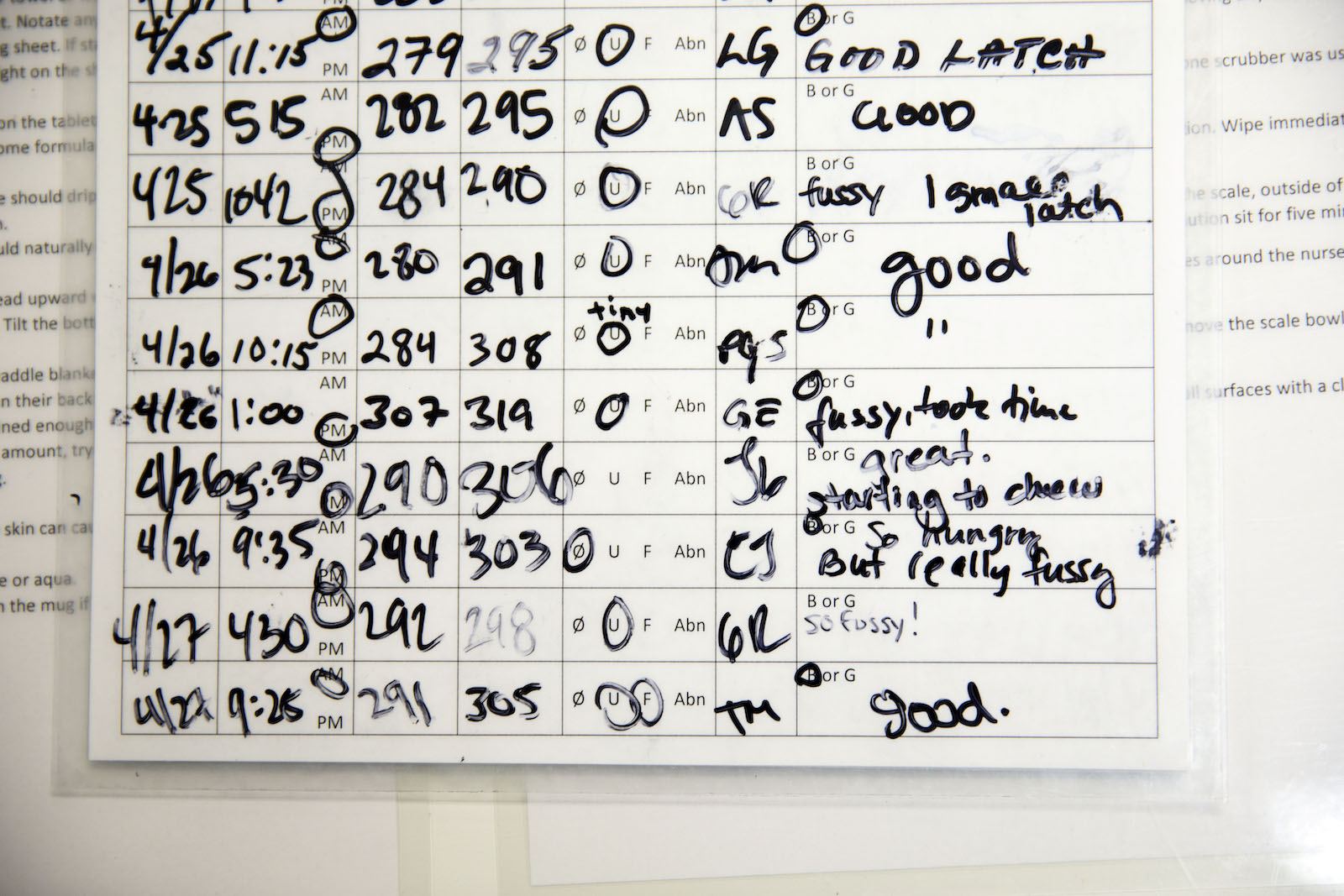

Unweaned kittens rest in terraria at the Best Friends Animal Society shelter in April 2017 in Mission Hills, California. A chart helps workers keep track of their behavior, weight and care schedule. Patrick T. Fallon / The Washington Post

Cats reproduce when females begin estrus, more commonly known as “going into heat,” during which hormones and behavioral changes signal that she is ready to mate. Cats can go into heat several times a year, with each cycle lasting up to two weeks. But births usually rise between April and October. While it is well established that lengthen the daylight induces a cat’s estrus, the effect of rising temperatures on the kittening season is not yet understood.

One theory is that milder winters may mean cats have the resources to start mating sooner. “No animal is going to breed unless they can survive,” said Christopher Lepczyk, an ecologist at Auburn University and prominent researcher of free-ranging cats. Outdoor cats’ food supply may also increase as some prey, such as small rodents, may experience population growth warmer weather themselves. Kittens may also be more likely to survive as winters become less harsh. “I would argue that temperature really matters,” he said.

Others, such as Peter J. Wolf, a senior strategist at the Best Friends Animal Society, believe the increase comes down to visibility rather than anything biological. As the weather warms, Wolf said people may be getting out more and spotting kittens earlier in the year than before. Then they bring them to shelters, leading to rescue groups feeling like kitten season is starting earlier.

Regardless of the exact mechanism, having a large number of feral cats around means trouble for more than just animal shelters. Cats are top predators that can wreak havoc on local biodiversity. Research shows that outdoor cats on islands have already caused or contributed to the extinction of an estimated 33 species. Feral cats pose a major threat to birds, which make up half of their diet. In Hawaii`i, known as a bird extinction capital of the worldcats are the most destructive predators of wildlife. “We know that cats are an invasive, environmental threat,” said Lepczyk, who has published articles proposing management policies for outdoor cats.

Scientists, conservationists and cat advocates all agree that uncontrolled outdoor cat populations are a problem, but they remain deeply divided over solutions. While some conservationists advocate the targeted killing of cats, known as culling, cat populations have been observed to jump back quicklyand a single female cat and her offspring can produce at least 100 descendants, if not thousands, in just seven years.

Although sterilization protocols such as “capture, neuter and release” are favored by many cat rescue organizations, Lepczyk said they are nearly impossible to do effectively, in part because of how freely the animals roam and how quickly they reproduce. Without homes or sanctuaries after sterilization, the return of cats outside means they can have a low quality of life, spread disease and continue to harm wildlife. “No matter what technique you use, if you don’t stop the flow of new cats into the landscape, it’s not going to matter,” Lepczyk said.

Rescue shelters, already under pressure from resource and veterinary shortages, are scrambling to confront their new reality. While some release material to help the community identify when outdoor kittens need intervention, others focus on recruitment for foster volunteer programs, which become essential care for kittens that need day and night care.

“As the population continues to explode, how do we address all these little lives that need our help?” Dunn said. “We’re giving it everything we’ve got.”