This story was originally published by Capital letter B.

Almost 45 years ago, the Acres Homes area north of Houston was the largest unincorporated Black community in the South, a flourishing area of 9 square miles where home ownership was the norm. That was until the city of Houston annexed it, and the Interstate 45 highway was built through its heart.

In the aftermath, the community’s poverty rate jumped to nearly double the city’s average, and health problems from pollution increased.

President Joe Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure bill, one of the nation’s most important investments in combating climate change, was supposed to consider the history of areas like Acres Homes in an effort to make communities whole again.

By creating a path to build the clean energy economy, from expanding electric school bus fleets to subways and mass transit options, it will also serve as a way to reverse the well-documented history of how the nation’s highways serve black communities. tore apart, to reverse. As residents were displaced, opportunities for home ownership were hampered, leaving black people exposed to pollution from cars and trucks and will probably die in car accidents.

Instead, the law actually increases pollution and contributes to the continued disruption and displacement of Black communities, according to a new report by the climate policy group Transportation for America.

According to the new report, what has mainly happened is a repeat of that history: freeways, freeways and more roads. Of the more than 55,000 projects totaling approximately $130 billion implemented by the $1.2 trillion spending package, nearly half of the spending was allocated to highway expansion.

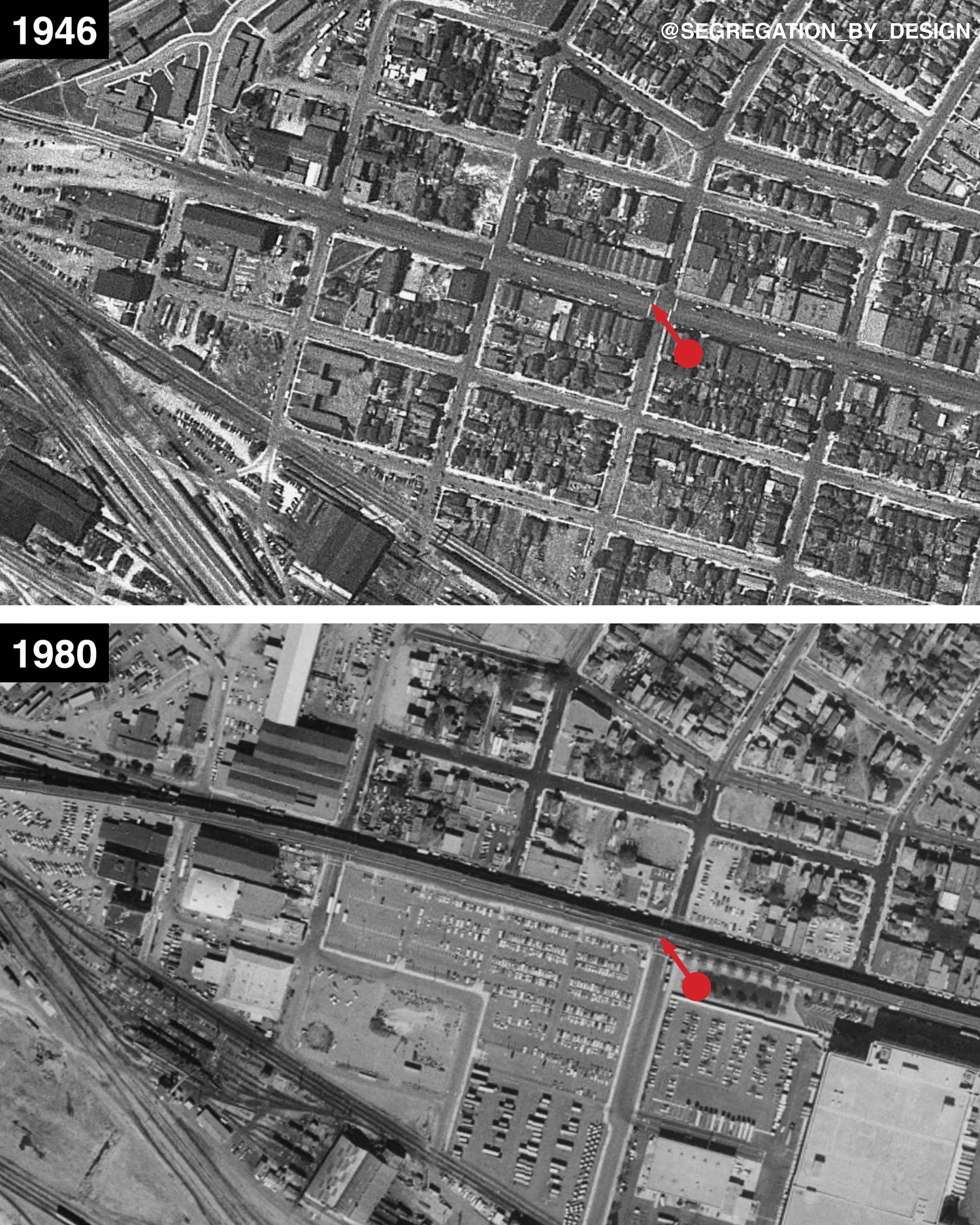

Adam Paul Susaneck and Segregation by Design

However, less than three weeks after the release of the report, the Biden administration announced a $3.3 billion spending plan to “reconnect and rebuild” communities in more than 40 states that were disconnected by highways throughout the 20th century. Some of the spending’s most prominent focuses include Milwaukee, Atlanta and Los Angeles, where public transit options will increase and some highways will be restricted.

Still, the spending pales in comparison to recent grants to expand highways.

Last year, the Biden administration supported a nearly $10 billion expansion of the same highway that tore through Acres Homes. The expansion resulted in the demolition of nearly 1,000 homes in a majority Black and Latino community.

It’s a mistake we’ve seen time and time again in this country, said Cherrelle J. Duncan, director of community engagement at LINK Houston, a policy organization focused on improving transportation options in Houston’s Black and Brown communities.

“Highways and their expansion don’t make your communities easier or reduce traffic. It doesn’t make your cars move faster,” she explained. “All it does is increase our air pollution, our noise pollution, and it also affects black communities and colored communities horribly by pulling resources, and also making them literally bypass and drive right past our communities.”

A study by Air Alliance Houston, an environmental justice nonprofit, found that levels of benzene, a carcinogen, would more than double at some schools along the expanded freeway.

Nationwide, the highway investment will virtually wipe out any positive climate benefits from other spending priorities. The simple result, the report found, is that the US would generate more emissions from transportation, already its biggest source of planet-warming gases, than if the bill had never passed. By 2040, the pollution created by these projects will be equivalent to running 48 coal-fired power plants per year.

Spending so far has created a “climate time bomb” that will also perpetuate the displacement of black communities, the report concluded.

It has even been known to exacerbate climate issues, such as in Elba, Alabama, where Capital B reported on how a new freeway expansion has exacerbated a flooding crisis in a rural Black community, leading to fears of flooding and displacing residents would become

Last month, a coalition of 200 climate organizations called for a national moratorium on highway expansions, especially because of the damage they caused in black and brown communities.

“We’re seeing infrastructure literally tearing us apart,” Duncan said. “We have created a division between communities so that we are no longer able to communicate with each other, while making it more difficult to build climate resilience, to stop floods or to flee in times of disaster.”

Why does this keep happening?

While the Department of Transportation under the Biden administration recommended that states prioritize repairing roads over expanding them and encouraged states to consider the impact on communities of color of decades of highway segregation, the spending law gave states considerable discretion in the allocation of funds.

As with many of Biden’s policies, it sparked a backlash from Republicans in Congress and was mostly overlooked by states like Texas and even California, which received the most money through the spending bill. At the same time, there has been little interest in improving access to public transportation, which has taken a hit nationwide after the pandemic reduced commuter revenue.

In Houston, Duncan saw firsthand how the nation’s renewed investment in freeways over other transit options was disrupting a new generation of Black children.

“If you have car-centric infrastructure,” Duncan said, “you’re simply going to have significantly worse air pollution, have more car accidents, and it’s all going to be centered in black communities.”

As Capital B reported last yearBlack people are almost twice as likely as white people to die in car accidents.

The struggle to reconnect communities

There were nationwide efforts to reconnect black communities disrupted by freeways. In Detroit, for example, where a vibrant Black community was destroyed for a freeway in the 1950s, there is a plan to eliminate the freeway. The Biden administration allocated $105 million to the project.

However, the plan is to replace the highway with a street that is six lanes wide and divided by a median for most of its length. Transit advocates say the current design is still too focused about the concerns of managers.

This path of “boulevardization” in communities disrupted by freeways is the main tactic implemented by cities across the country. This approach involves removing freeway structures entirely and replacing them with urban boulevards, but as in the case of Detroit, it may still prioritize cars rather than city dwellers. In some cases, it has even resulted in perpetuating and crowding out the very communities it aims to support.

depiction of Adam Paul Susaneck and Segregation by Design

One of the earliest examples of boulevardization, which took place in Oakland, California in the early 1990s and has been used as a prime example of the process’s success, actually caused the neighborhood’s Black population to drop by a third as the median household income increased. by 55 percent between 1990 and 2010.

This is a perfect example of intent that is never realized because black communities are not listened to, Duncan said.

“It is extremely important for every agency and city organization to engage diverse voices when it comes to planning transportation,” Duncan said. “If you’re going to actively tear our communities apart and actively separate them through freeways, the least you can do is really listen and engage them to ensure these project solutions and policies don’t overlook us again.”

Over the past year, Duncan’s organization has worked to gather community input for similar freeway removal efforts and calls for investment in walkability and public transportation; she hopes leaders will listen.