This story is published as part of the Global Indigenous Affairs Desk, an Indigenous-led collaboration between Grist, High Country News, ICT, Mongabay, Native News Online and APTN.

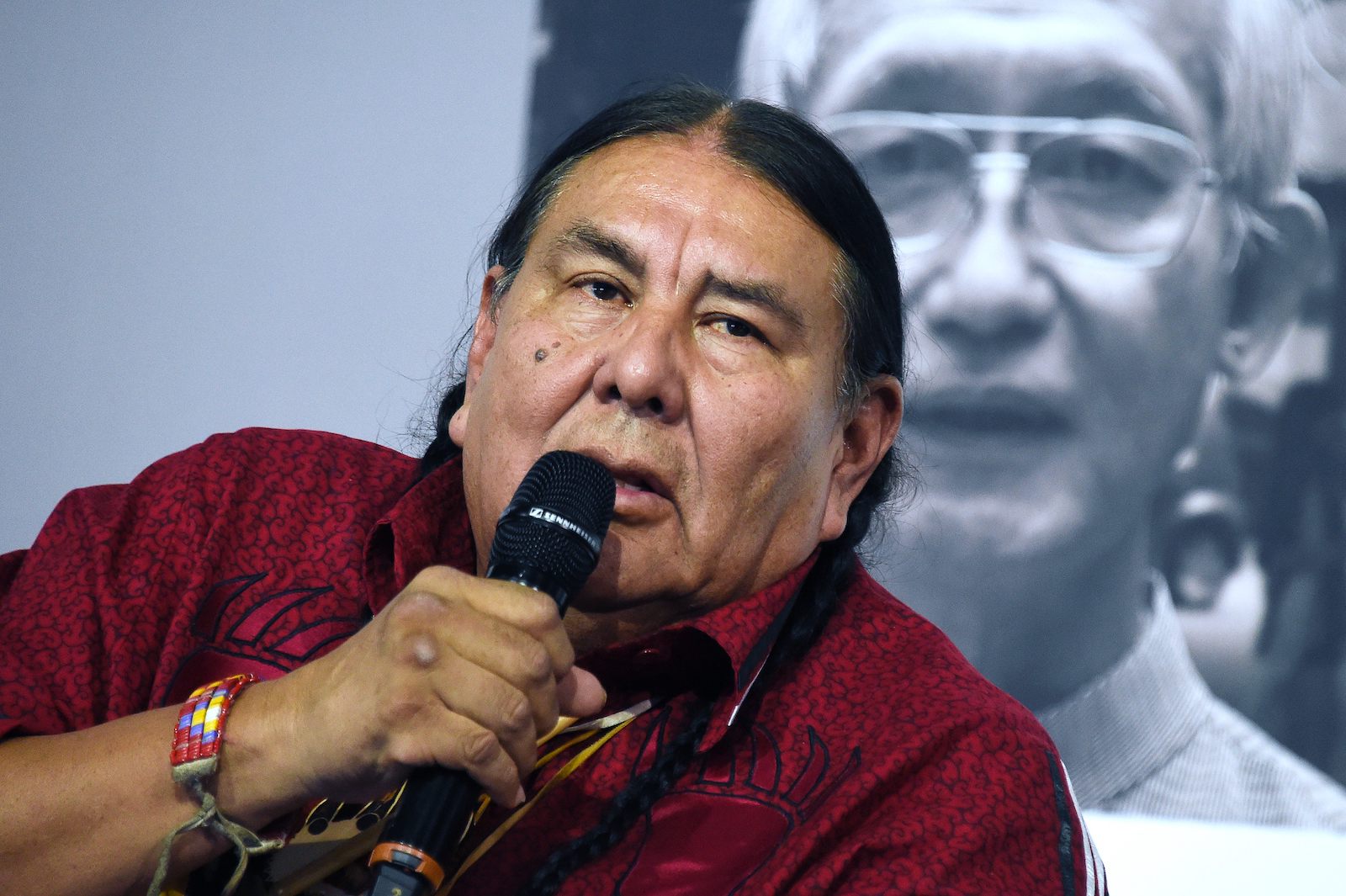

For more than 20 years, Tom Goldtooth has listened to conversations about the negative impacts that fossil fuels and carbon markets have on indigenous people. On Wednesday, Goldtooth and the Indigenous Environmental Network, or IEN, called for carbon markets to be permanently ended. Besides being an ineffective tool to mitigate climate change, the organization argues; they harm, exploit and divide indigenous communities around the world.

The recommendation was delivered to a crowd of indigenous activists, policy makers and leaders at the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Affairs, or UNPFII, and is the most comprehensive moratorium on the issue the panel has yet heard. If adopted, the position would push other United Nations agencies – such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC – to take a similar stance. The increased urgency stems from the COP29 meeting planned for later this year, when provisions in the 2015 Paris climate agreement on carbon market structures are expected to be finalised.

“We are long overdue for a moratorium on bogus climate solutions like carbon markets,” said Goldtooth, who is Diné and Dakota and executive director of IEN. “This is a life and death situation with our people related to the mitigation solutions being negotiated, especially under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Article 6 is all about carbon markets, which is a smokescreen, which is a loophole [that keeps] fossil fuel polluters agree to phase out carbon.”

Dominique Faget / AFP via Getty Images

The Network’s language about “false climate solutions” is intentional. Tamra Gilbertson, the organization’s program coordinator and climate justice researcher, said a fake climate solution is anything that looks like a tool to reduce emissions or fight climate change, but allows extractive companies to continue to profit from the fossil fuels which drives the crisis.

“Carbon markets were set up by the polluting industries,” Gilbertson said. “The premise of carbon markets as a good mitigation outcome or a good mitigation program for the UNFCCC is itself a flawed concept. And we know that because of who put it together.”

The carbon market moratorium called for by the network would end projects for the removal of carbon dioxide carbon capture and storage; forest, land and sea landslides; nature-based solutions; debt-for-kind swaps; biodiversity offsets, and other geoengineering technologies.

This year’s moratorium recommendation builds on a similar proposal the IEN presented at last year’s Forum, when it called for carbon markets to be halted until indigenous communities “can thoroughly examine the impacts and make appropriate demands.” That call led to an international meeting in January, where indigenous experts discussed the impact that a green economy has and would have on their communities. Finally, the participants produced a report detailing how green economy projects and initiatives can create a new way to colonize indigenous peoples’ lands and territories.

Darío José Mejía Montalvo, from the Zenú tribe in Colombia, participated in the January meeting and chaired a previous UNPFII. He highlighted the report during a UN session last week.

“The transition to a green economy [keeps] starting from the same extractivist-based logic that prioritizes the private sector, which is guided by national economic interests of multinational corporations, which ignores the struggles of indigenous peoples, the fight against climate change and the fight against poverty,” Montalvo said, according to a UN translation of a speech he gave in Spanish.

Evaristo Sa / AFP via Getty Images

Goldtooth and Gilbertson say that while the January report established wider consensus on the negative impact of the green economy, the IEN felt that the report’s recommendations were unclear and did not go far enough to discourage the growth of carbon markets – and that is why the organization is calling for a permanent moratorium.

“We have to do everything we can from every direction we possibly can in this climate emergency that we’re in, because we don’t have a lot of time left,” Gilbertson said. If carbon markets are enshrined in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement as currently written and become a more powerful international network, “we are in a whole new era of connected global carbon markets like we have never seen before. And then we’re stuck with it.”

Under the Paris Agreement, countries submit plans detailing how they will reduce emissions or increase carbon sequestration. Article 6 provides pathways for nations to cooperate and trade emissions on a voluntary basis to meet their climate goals. More specifically, paragraph 6.4 will create a centralized market and lead to large-scale implementation of trading in emission reductions. The nuances of these structures and how carbon markets are presented in Article 6 have far-reaching impacts: A report released in November by the International Emission Trading Association, or IETAshowed that 80 percent of all countries indicate that they will or will use carbon markets to meet their climate goals.

In its current form, carbon offset projects as described in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement will further threaten indigenous land tenure and access to resources. If finalized in November, pilot projects are expected to begin as soon as January 2025.

At this year’s Forum, organizations such as the United Nations Development Programme, Climate Focus, Forests Peoples Program and Rainforest US discussed new initiatives to protect indigenous peoples’ rights within a carbon market. In particular, there is increased attention to policies that would more effectively incorporate free, prior and informed consent, or FPIC, into carbon offset operations. But Kimaren Riamit, executive director of ILEPA-Kenyaa Native-led nonprofit, said the foundation to be established even before FPIC is better recognized Native self-determination — agency for tribes to decide for themselves whether they want to get involved in carbon market projects at all.

“FPIC without enablers of self-determination is useless because what are you consenting to when your land rights are not there? What are you giving permission for if you are not part of the decision management arrangement?” said Riamit, who is from the Masai tribe in Kenya. Enablers of self-determination include protection for indigenous land sovereignty and land tenure security.

Riamit says that free, prior and informed consent in carbon market projects has become a strategic tool and a confusing exercise in disseminating information rather than a means of obtaining meaningful consent from tribes. There must be deliberate and full disclosure to tribes of what they are agreeing to when they engage in a carbon market project, and time for them to digest the information, consult internally, provide feedback, and – critically – “be able to say no say. ”

It is noteworthy to Riamit that companies with carbon offsets do not strongly, if at all, advocate for improved self-determination of the indigenous communities they work with.

“They don’t sharpen a knife to slaughter themselves,” he said.