The experiment began by chance.

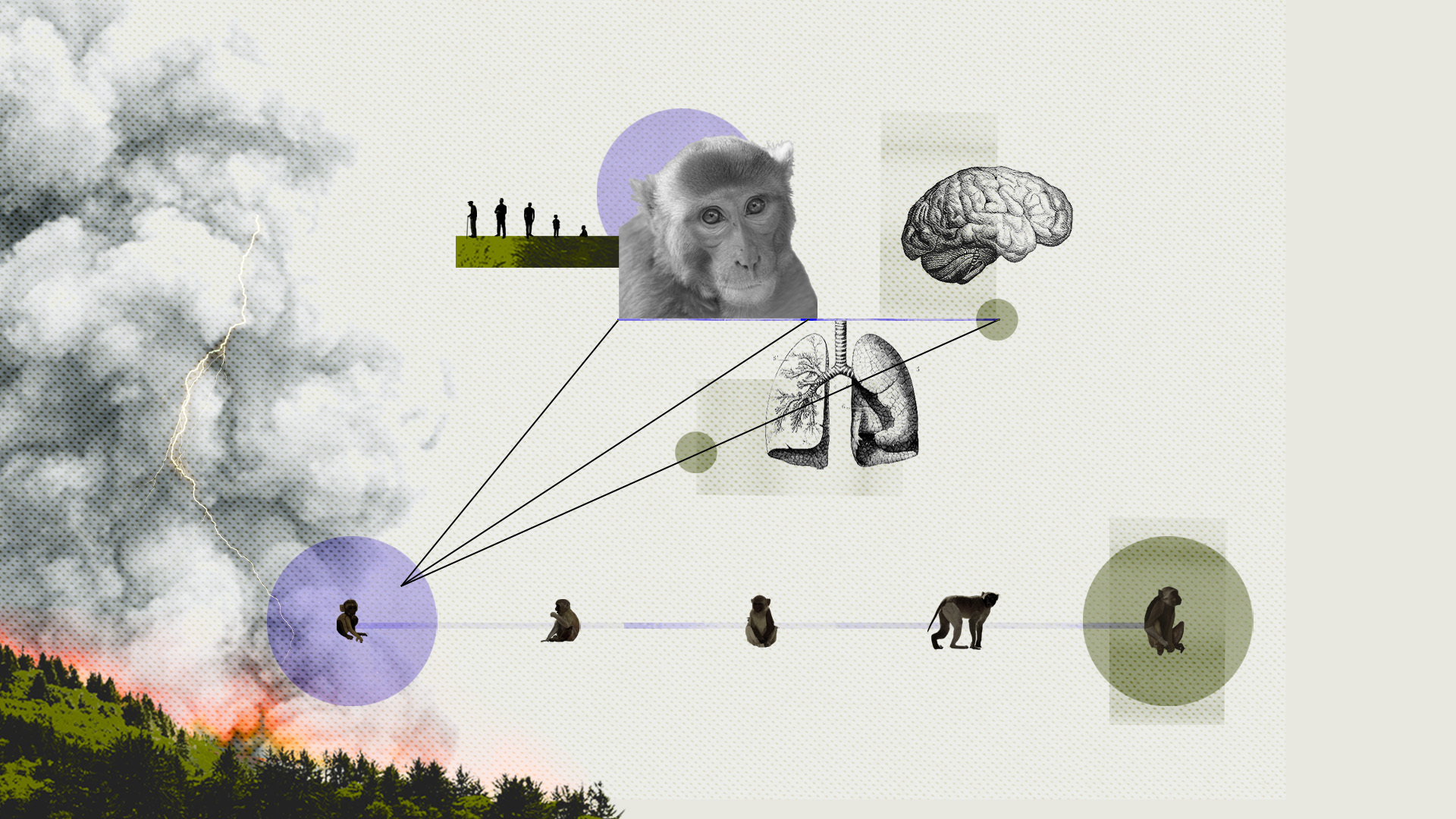

In 2008, summer lightning storms caused a chain of wildfires in the forests of Northern California. Smoke blanketed the state for weeks and drifted as far as the California National Primate Research Center, where 50 rhesus monkeys had just been born.

“I looked out the window and it looked like the middle of winter here in the Sacramento Valley,” said Lisa Miller, an associate director of research at the center.

NASA

Across Northern California, air quality has dropped to unhealthy levels. People living and working in the valley inhaled smoke day after day. And so were all the local outdoor animals – including the monkeys at the research center. As the smoky days continued, Miller kept thinking about the primates, whose habitat she could see from her office window.

The gears in her head started turning. “As a scientist, our minds are always thinking about the next question and trying to put the pieces together,” she said. Miller wondered if this generation of monkeys might finally hold the answer to a public health mystery: how early smoke exposure can ripple over a lifetime.

That twist of fate — a lightning strike, a wildfire and a primate lab caught downwind — ended up giving researchers a rare look at the surprising lifelong health impact of smoking on animals and people.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Scientists know the short-term effects of wildfire smoke on people – irritating the lungs, or causing asthma or heart attacks. They also found many clues that point to long-term health impacts, but these are incredibly difficult to study. In an ideal experiment, scientists would compare nearly identical groups, where the only difference is the exposure. But people live incredibly messy lives: People breathe different air, work different jobs, eat different foods, live in different houses, take different drugs and move to different places. All these factors make long-term environmental health studies extremely difficult.

But at the primate research center, Miller realized they had all the ingredients for a natural experiment that could cut through all that noise. Rhesus monkeys are remarkably similar to humans. The monkeys at the center all lived together, ate the same food and breathed the same air. There happened to be a state air monitor a kilometer away, which allows them to track pollution levels 24 hours a day. The generation of monkeys born the following year was a perfect control group: identical in all respects except the exposure to wildfire smoke. And since rhesus monkeys age faster than humans, Miller was able to observe the groups for just a few decades to get a sense of wildfire smoke over the life course.

“It was really, in my opinion, serendipity — in the sense that we were in the right place at the right time,” she said.

Miller’s team began studying these two groups of monkeys and compared those exposed to the smoke to those that were not. They continued to study them for 15 years. They tested the animals’ lung function, used CT scans, took blood draws – everything that humans might experience during a medical visit.

One theory, based on Miller’s earlier work on primate health, was that air pollution could weaken the monkeys’ immune systems. To test this, researchers drew blood from the monkeys, and in the lab they added small bits of bacteria and viruses to see how the immune cells would react.

Jesse Nichols / Grist

They found that the exposed monkeys initially had weaker immune responses, leaving them vulnerable to infections. But in later years there was a twist. “Interestingly, as the animals matured, it actually turned,” Miller said. Once the exposed monkeys reached adulthood, their immune systems switched from weak to hostile, causing unhealthy levels of inflammation.

This finding was quite shocking on its own. But that was really just the beginning: After CT scanning all the monkeys’ lungs, Miller’s team found the wildfire smoke led to lifelong physical changes. The smoking cohort had smaller and tighter lungs that could hold about 20 percent less air than the lungs of the cohort not exposed as newborns.

“The CT scan images were quite amazing,” Miller said. “The physical change we detected in the animals as juveniles appears to remain with the animals five years later, [even] 10 years later.”

Because the monkeys exposed to smoke had smaller lungs, the researchers at the center assumed they would be less active than the others. To test this, they invented what was essentially a Fitbit for monkeys, custom 3D printing each a collar with a little motion sensor inside.

Looking at the data, they found that the smoky group of monkeys, despite their smaller lungs, were actually more active—because they slept less. The smoking monkeys had a completely different, and less restful, sleep cycle. Because humans are so similar to rhesus monkeys, this study suggested to Miller that early exposure to wildfire smoke may contribute to some of the chronic diseases we see in humans later in life.

“It’s this first year of life, this very early window of development for people that is so critical to imprinting long-term health,” she said. “If you can control the environment during this period, you may set the stage for a longer, healthier life in the future.”