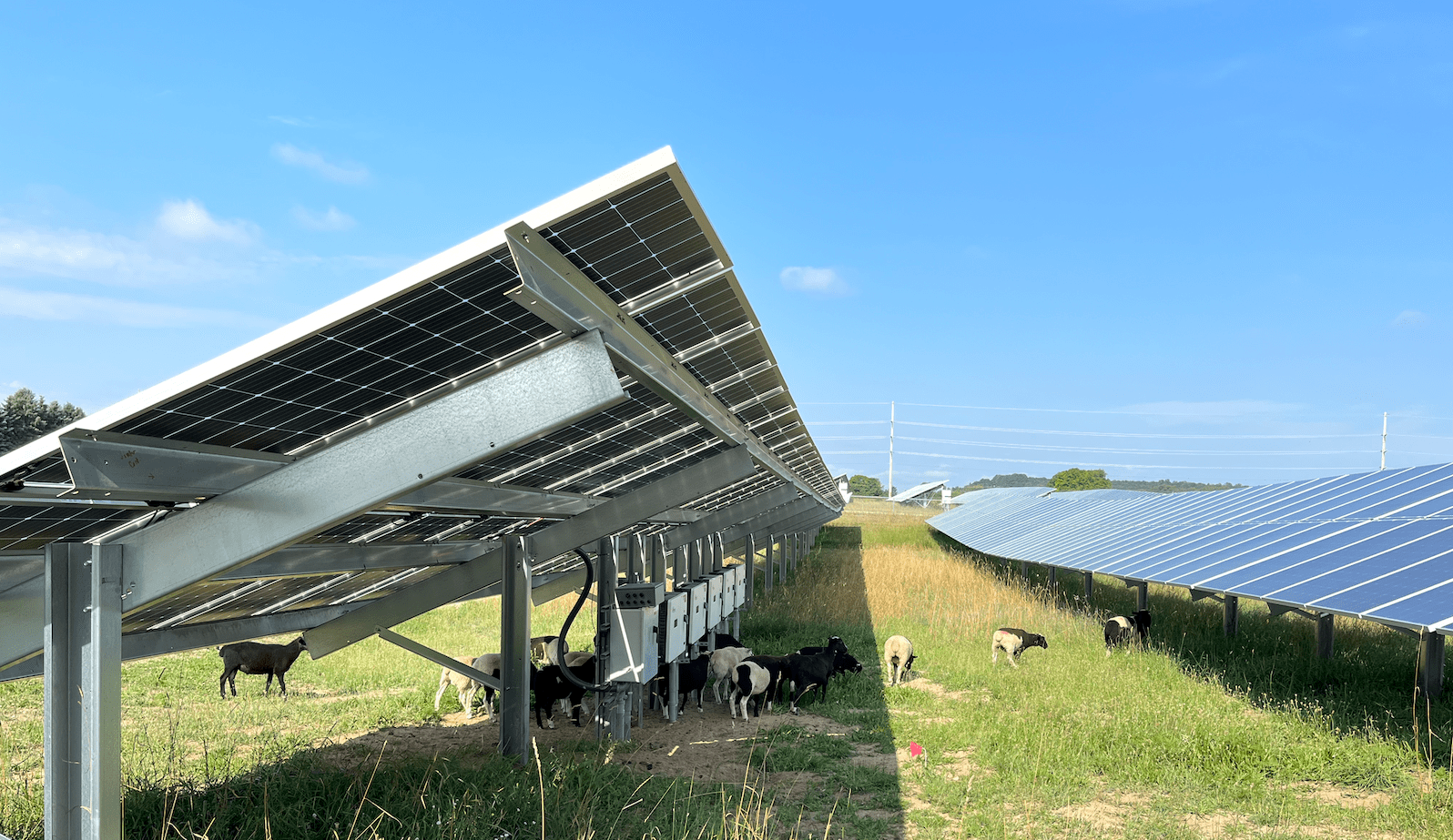

As a herd of around 2,000 sheep graze between rows of solar panels, shepherd Tony Inder wonders what all the fuss is about. “I’m not going to suggest that it’s everyone’s cup of tea,” he says. “But when it comes to sheep grazing, solar is really good.”

Inder talks about concerns about the encroachment of prime agricultural land by ever-expanding solar and wind farms, a trodden talking point for the staunchest opponents of Australia’s energy transition.

But on Inder’s property in New South Wales, a solar farm has increased wool production. It’s a symbiotic relationship that National Renewables in Agriculture Conference director Karin Stark wants to see replicated across as many solar farms as possible as Australia’s energy grid transitions away from fossil fuels.

“It’s all about farm diversification,” says Stark. “At the moment many of our farmers are dependent on when it will rain, solar and wind provide this secondary income.”

By keeping the grass trimmed, which can otherwise pose a fire risk during dry summer months, sheep save the developer the cost of cutting it himself.

In return, the panels provide shelter for the sheep, encourage healthier pasture growth under the shade of the panels and create “drip lines” of condensation that roll off the front of the panels.

“We’ve had strips of green grass right through the drought,” says Dubbo sheep grazer Tom Warren. Warren has seen a 15 percent increase in wool production as a result of a solar farm installed on his property more than seven years ago.

Despite these success stories, a 2023 Agrivoltaic Resource Center report authored by Stark found that solar grazing in Australia is underutilized because developers, despite intending to house livestock, make few planning adjustments to ensure that it happens.

“The result is that many solar farms are poorly suited for sheep,” says Stark. “Developers need to talk to landowners earlier than they currently are.”

Prof Bernadette McCabe, the director of the Center for Agricultural Engineering at the University of Southern Queensland, says farming and solar energy are “two very different activities” and there is “minimal research and demonstrated success” in operating them in combination.

The expectation to retain farmland for primary production is driving greater interest in the coexistence of agriculture and renewable energy, but McCabe says “misaligned incentives” between developers and farmers need to be better managed.

It’s these conflicting goals that give anti-renewable voices “fodder to attack the renewable energy industry,” according to former New South Wales solar developer Ben Wynn.

He says energy developers “often talk about the possibility” of co-existing with livestock production, but have no “genuine desire to do so”.

Wynn is now part of a community group opposing a large solar farm proposed south of Tamworth because it sits on productive cropland.

“We need this transition to speed up, but if we take up highly arable black soils, we give oxygen to the naysayers,” he says.

Wynn also led the construction of a prototype solar farm outside Tamworth, raised high off the ground with steel poles to stay out of reach of a herd of cattle below.

“Cattle are massive, they’ll rub and scratch themselves against anything,” says Wynn.

The project was a success, but Wynn says it is too expensive to be feasible on a large scale because the installation costs are three to four times the cost of regular low-lying solar panels.

The integration of sheep and solar power is “highly feasible”, says McCabe, because they can graze under normal height panels. But she says it is “still early days” to know if it will become economically viable for cattle.

Dr Nicholas Aberle, the energy generation and storage policy director at the Clean Energy Council, says solar developers should explore dual land-use options, but warns they may not be suitable for every project. He adds that “the abundance of land in Australia means it’s not always necessary.”

According to an analysis by the Clean Energy Council, less than 0.027 percent of the land used for agricultural production would be needed to power the East Coast states with solar projects – much less than one third of all prime agricultural land that the right-wing think tank the Institute for Public Affairs claimed would be “taken over” by renewable energy. That argument, what was heavily refuted by expertswas taken up by the National party, whose leader, David Littleproud, said regional Australia had saturation point has been reached with renewable energy developments.

Queensland grazier and the chair of the Future Farmers Network, Caitlin McConnel, has sold electricity to the grid from a dozen custom solar installations on her farm’s cattle pasture for more than a decade.

“Trial and error” and years of modifications have made them structurally sound around cattle and made them financially viable in the long term, she says.

“As far as I know, we’re the only farm doing solar with cattle,” says McConnel. “It’s good land, so why would we just lock it up for solar panels?”