In an oft-excerpt from his memoirs Life on the Mississippi, Mark Twain describes how his perceptions of the Mississippi River changed after months of piloting a steamboat up and down its muddy length. “The face of the water became a wonderful book in time,” he said, letting him read the twists and turns that meant nothing to his passengers. But the tragedy of this “valuable acquisition” was that “the romance and the beauty were all gone from the river.”

“All the value that any feature of it now had to me was the amount of utility it could offer in bypassing the safe pilotage of a steamer,” he writes.

Even for those of us who will never pilot a steamboat, there is a residual lesson in this passage about how we perceive and talk about the environment. A body of water like the Mississippi River is something we experience with our eyes, ears and noses, and it is largely because of its beauty that we want to protect it. But it also has a specific human history – the river runs between artificial banks, or provides transportation for ships carrying oil, or drains toxic runoff from factory farms.

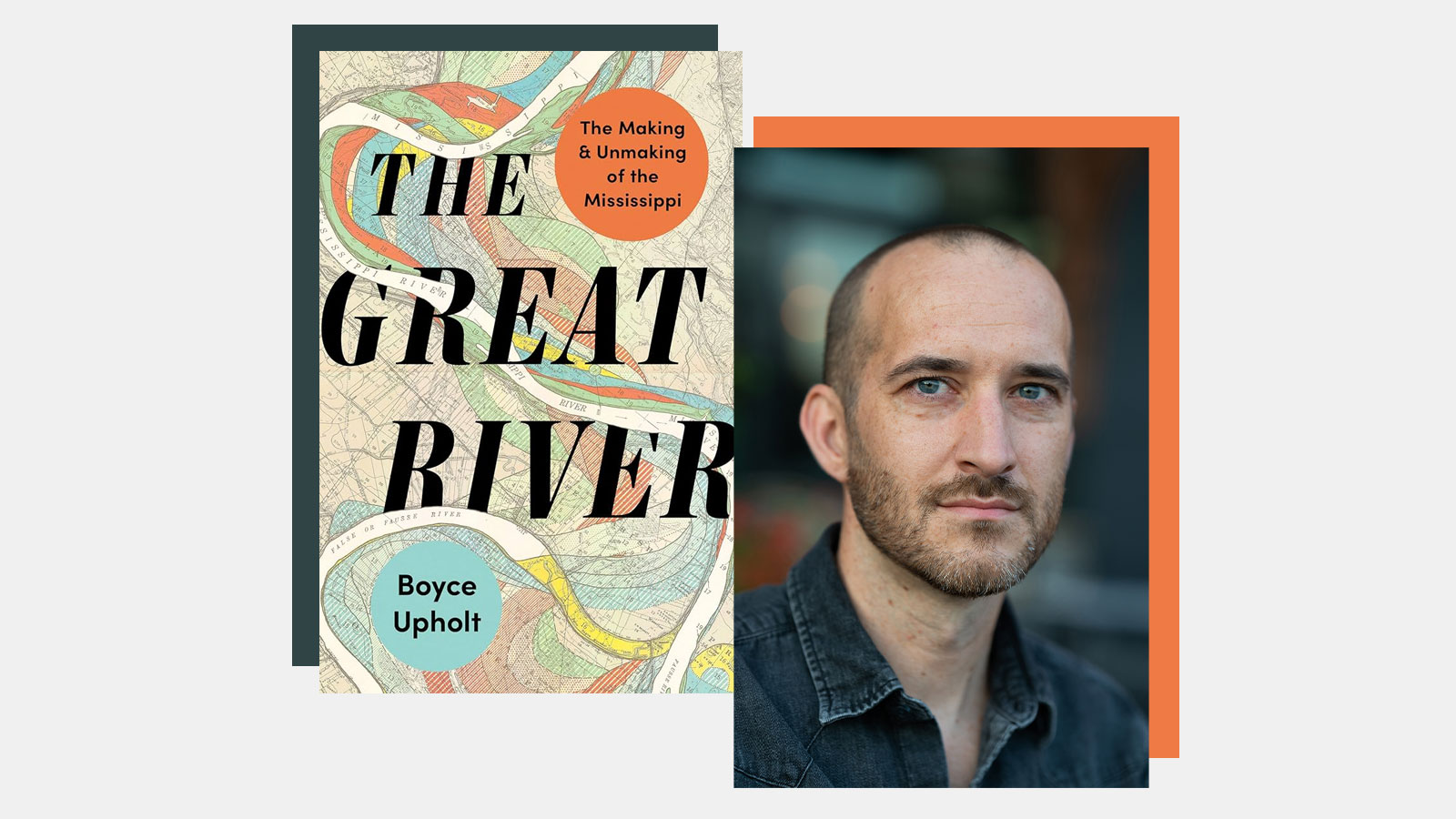

In his fascinating new book The Great River, author Boyce Upholt tells the story of the Mississippi, not through the eddies and mudflats that Twain passed in his steamboat, but through the stories of men who have tried to master the river for more than two centuries. Spanning thousands of miles, it demonstrates how the United States has distorted and manipulated one of the world’s largest watersheds in the short-sighted service of economic development, often with catastrophic unintended consequences. If Twain reads the river as a book, Upholt gets more specific and reads it as a tragedy wrought by colonial hubris.

This focus on the people who carved and dredged the river for their own ends, rather than on the wilderness of the river itself, provides a story that holds profound lessons for coastal cities and western deserts as well as those who live in the river’s vast watershed. .

The most interesting question, Upholt argues, is not how the Mississippi River will fare in a changing climate, but what the history of that river tells us about how the rest of us will fare. Reviewing how “engineers worked to tame this god,” he sounds an alarm about other attempts to control the flood of nature. For all our expertise and ability, he argues, we are little more powerful than the boat passengers whom Twain mocked as blind to the river’s ways.

The first section of the book tells of the centuries that preceded this attempt at domination. Upholt examines a growing body of archaeological research on various Native societies that rose and fell along the Mississippi many hundreds of years before European settlers arrived, including one city, Cahokia, in present-day Illinois, which housed more than 10,000 people around a housed a central pyramid. than a hundred feet high. He ponders the cosmic purpose of earthwork mounds like those in Poverty Point, Louisiana, which represent “Indigenous knowledge encoded in the land,” and tells a story in which “a flood is not a catastrophe, but a asset.”

Once the colonists arrive and President Thomas Jefferson sends them into the Midwest, Upholt swings up and down the main stem of the river and along its major tributaries, the Missouri and the Ohio, describing how fur traders made their way downstream in ” keelboats” spat. [that] embraces the inner turns of the river’s curves,” enhanced by “whiskey chased by a cup of river water”. Upholt announces at the beginning of the book that he will not proceed in strict chronological order, which is understandable since his book is not a traditional work of history, but his attempts to switch back and forth in time as well as between various tributaries can often leave the reader feeling lost.

However, the book hits its narrative stride once Upholt introduces the Army Corps of Engineers, the federal agency that has controlled the river for nearly two centuries. Since the 19th century, the Corps has spent countless billions of dollars dredging, diking, damming, de-damming, channelizing, diverting, diverting and diverting the river in an effort to control flooding and facilitate navigation for cargo. This bold attempt to tame Mother Nature met with what can charitably be described as middling success, and some of the best sections of the book are those in which Upholt describes the many river and dredging projects the Corps built against the better. judgment of river experts, as well as common sense.

The bickering engineers who led the Corps, often unhappy but always unfailingly self-serious, are the closest Upholt gets to main characters, and their stories function as parables about the relationship between the US and the environment it sought to colonize and reshape. The most famous of these was the match between James Buchanan Eads, a brilliant civil engineer who advocated making room along the river’s banks for its water to flow and flood, and Andrew Humphreys, an army general who advocated for the sealing most of the river with people. -walls made. Humphreys won the debate, with catastrophic results: In 1927, as the Corps of Engineers was finalizing its levees along the lower river, a massive flood burst through and flooded much of Louisiana and Arkansas, inundating 500 killed people and displaced hundreds of thousands more.

A more sympathetic character is Harold Fisk, an Army cartographer who designed beautiful cards of the river’s remaining paths, showing how it meandered back and forth across the Heartland in the centuries before the Corps walled it off—one such map graces the cover of Upholt’s book. Fisk’s now-legendary ribbon map “highlighted rather than obscured the wildness of the Mississippi,” discovering in the process that the river was about to burst its banks in Louisiana and rush southwest away from New Orleans, which would left high and dry.

The climax of the book is when Upholt visits the Old River control system, which is designed to keep the river in place and prevent Fisk’s prophecy from coming true. As he approaches the site, Upholt sees “concrete wing walls flaring outward, water flowing toward a series of five steel gates” held up by giant beams, and then “just upstream a second line of gates, six times taller, looms over ‘ a patch of patch… of a concrete walkway built next to the confluence, the river looked like a varicose vein… so swollen it was ready to jump.”

It’s hard to understand modern Mississippi until you’ve seen this structure. His hubris typifies the destructive human endeavor that Upholt tries to portray throughout the book, and holds a lesson for regions and nations trying to tackle the threat of climate change. If the world’s richest and most powerful nation struggled to tame nature before the Earth warmed by a degree and a half, it does not bode well for its efforts to stem sea-level rise with concrete walls or solve drought problems by not build more dams.

But the solution, as Upholt makes clear in the end, is not just to tear it all down, to insist on seeing the river as a pure manifestation of nature. Rather, he points us back to the indigenous earthworks that preceded colonization, remnants of a society that tried to live with the rhythms of a flood-prone river rather than changing those rhythms to meet human needs, and a harmony between Finding Twain’s two ways of seeing. the Mississippi.

“This river has never been alone,” writes Upholt after seeing an earthwork in Louisiana near a village of the Grand Bayou Atakapa-Ishak/Chawasha tribe. He goes on to describe the half-submerged earth structure as “a monument … not to the beauty of empty nature, but to the possibility of a human connection”; rather than a “celebratory” structure, he sees the hills as “insurance, an anchor in the midst of chaos. They offer a lesson in how to respect nature without seeing it as something separate from human life.”

On the issue of climate change, an area where politicians often appeal to the ferocious power of nature and to our ability to correct the course of the earth itself, this is a point well taken. To truly achieve sustainability, on the Mississippi or elsewhere, we will have to give up some control.