Solar panels. Heat pumps. Electric buses. Those are just three of the things the Chicago Teachers Union, or CTU, hopes to achieve in their latest negotiations for a new contract, one that will address the rising toll of climate change in the more than 500 schools where their members teach.

Arguably one of the most powerful teacher unions in the country, the CTU held public negotiations last Friday in a packed elementary school gym, against leaders of Chicago Public Schools, or CPS.

The two entities have a contentious relationship, made clear in the past decade with two strikes and several showdowns during the pandemic. The negotiations were also streamed, but any observers expecting the usual verbal fireworks will be disappointed. Both sides agreed that climate change is a real challenge. Now they just have to figure out how to pay for the necessary changes.

“Chicago’s buildings, including school buildings, are a huge source of carbon emissions,” said Lauren Bianchi, a social studies teacher on the city’s Southeast Side and chair of the CTU’s Climate Justice Committee. “CPS buildings produce annual emissions equivalent to approximately 900 train cars of coal.”

Nationwide, the Biden administration has encouraged school districts to start thinking about reducing their climate emissions. To that end, the federal government has poured in millions of dollars in federal grants and technical assistance to help schools install solar panels, buy electric buses and update heating and cooling systems. But from California on Massachusettsteacher unions have already started to get tough on climate justice demands.

As heat and extreme weather become more common because of the climate crisis, J. Mijin Cha, an environmental studies professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said it makes sense for climate demands to come up in union negotiations.

“If you want a green school, you really have to think about what the challenges of the climate crisis will bring to students trying to study,” Cha said. “Things like heat and other things that will worsen as a result of the climate crisis are then educational issues.”

In April, Stacey Davis Gates, the union’s president, issued a “transformative” contract proposal in which increased wages were just a starting point. The plan included hundreds of items ranging from a plan to build more affordable housing in the city to providing additional resources for the thousands of migrant children being transported to Chicago from the Mexican border. Additionally, the union wants energy efficiency and climate resilience in their new contract.

For starters, the CTU wants to bring the school district’s aging infrastructure into the 21st century. On average, Chicago’s school campuses are more than 80 years old, twice the national average according to the National Center for Educational Statistics. The oldest school still in operation dates back to 1874, the same year as the Great Chicago Fire.

And keeping the lights on in the city’s old public schools isn’t cheap.

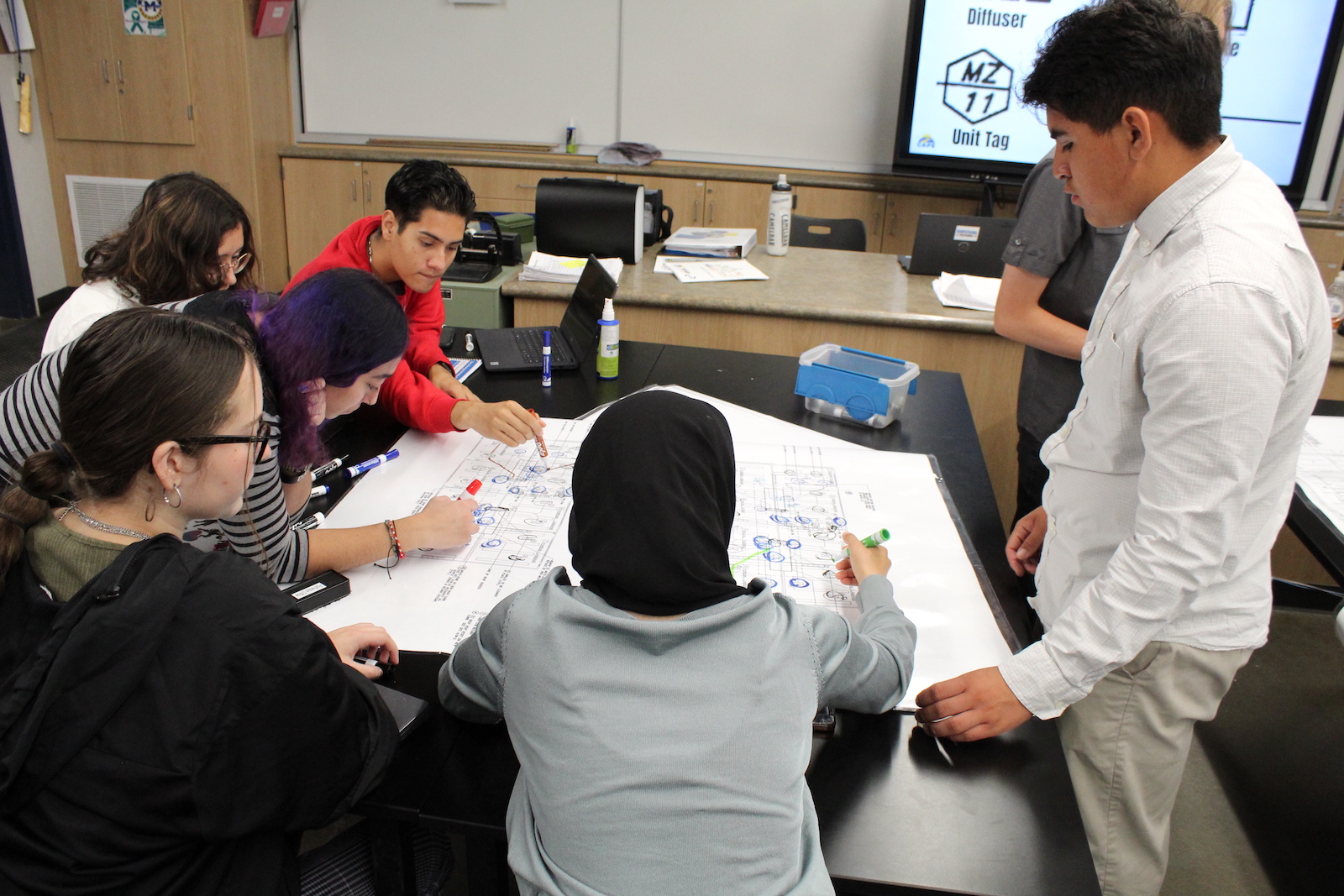

Juanpablo Ramirez-Franco / Grist

“Chicago Public Schools will face more than a billion dollars in climate-driven cooling costs by 2025,” explained Ayesha Qazi-Lampert, an environmental science teacher.

The CTU wants to transform the city’s schools into “climate-proof community centers,” Qazi-Lampert told the crowd. To do that, the union wants the school district to install heat pumps, switch to solar and geothermal power, and get all lead contamination out of the school’s drinking water.

Outside the school campuses, the teachers’ union wants more green spaces — extensive urban canopies and native gardens that beautify the neighborhood and collect stormwater.

“Our school buildings are not designed to withstand frequent and immediate hot and cold extremes,” Qazi-Lampert said. “Not only are we testing the integrity of the building materials, but we are adding stress to already outdated cooling and heating systems.”

It is not only physical infrastructure that the union wants to modernize, but also what happens inside classrooms and cafeterias. The CTU is calling for expanded career technical education that puts Chicago students on track for jobs in the emerging clean energy economy. And better lunches for the students to sustain students while learning inside their new solar powered school.

But these updates won’t be quick and they won’t come cheap. Money, especially in the coming year, is in short supply. CPS is facing a nearly $400 million shortfall for the next school year as pandemic relief funding begins to dry up.

On top of the looming budget shortfalls, CPS Chief Facilities Officer Ivan Hansen said there is already a massive backlog of deferred updates. “Our total immediate critical need in the district is over $3 billion and that’s just to get the buildings into good repair,” he said.

Still, CPS leadership agrees with the union on the broadest points: CPS has a massive footprint across the city, with more than 62 million square feet of building space and most of it is deteriorating. The city still had questions about the finer details.

In one instance, David Singler, the energy and sustainability program manager for CPS, dismissed the union’s plans to mass install solar panels. “If we were to take every square inch of roof and put a solar panel on it, it would only generate a fraction of the amount of energy we need in the district to operate our buildings,” he said.

Before concluding their first public bargaining sessions, CPS and CTU agreed to work more closely together on grant applications in the future. Almost everything else is left up in the air.

But the union is intent on getting the district to enshrine its climate mitigation proposals in the upcoming contract. Davis Gates explains that responding to climate change must be a priority, not just for the union, but for the district.

“That contract means nothing when our earth is on fire,” she said.