The vision

“When you lose that, you’ve lost a record of climate on Earth that can never be recovered. There are many scientists who realize this, and have realized this for decades, who are making heroic efforts to recover this ice before it disappears forever.”

– Nuclear scientist Tyler Jones

The spotlight

The first time Tyler Jones visited the National Science Foundation’s Ice Core Facility in Colorado’s Jefferson County, he felt like he had stepped into an episode of. The X-Files. “It was like I was in some secret government institution,” he said. Jones, an ice core scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder, likened the facility to a “giant walk-in freezer” housed in an old concrete building, where scientists preserve cylinders of glacial ice that essentially serve as time capsules of information.

The coldest chamber of this enormous freezer is filled with shelves bearing the weight of ice cores from both poles, stored in protective metal tubes, dating back decades. “It’s basically a giant library of ice cores,” Jones said — a library that some of the first ice cores ever taken

Portions of samples from as far back as the 1950s are preserved at the facility because scientists have long known that as technology has advanced, it will allow future generations to analyze old samples in new ways. “We always try to save some ice to give those future scientists a chance to do something better than what we’re currently doing,” Jones said.

This desire to preserve ice cores has taken on a new urgency given how rapidly glaciers are melting around the world. When the average person thinks of this problem, they may imagine icebergs falling into the ocean and mountain slopes left barren as the ice recedes down a slope. But glacial melt also has an invisible impact within the ice itself, rapidly erasing the data that glaciologists and climate scientists rely on to learn about planetary changes.

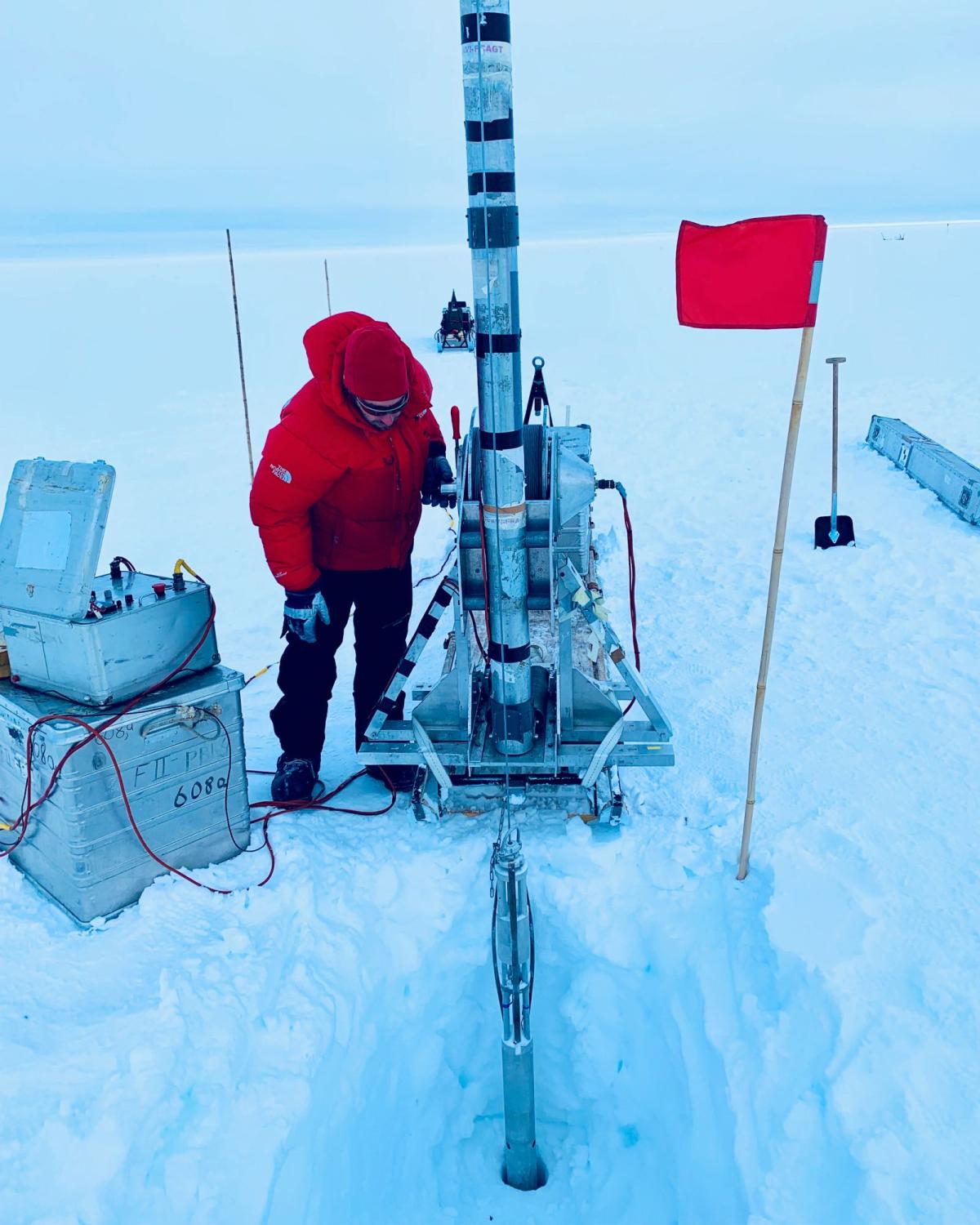

A piece of an ice core extracted by a research team in Svalbard, Norway. Riccardo Selvatico for CNR and Ca’ Foscari University of Venice

About 10 years ago, Carlo Barbante, a chemist at the University of Venice in Italy, and his glaciologist colleague Jérôme Chappellaz of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology had the idea for an initiative that would extend the work of the Ice Core Facility in Colorado would complement similar facilities in other countries: an international Ice Memory Sanctuaryfocused on preserving cores extracted from endangered glaciers.

The sanctuary was built as a cave last year on the High Antarctic Plateau, where the average temperature is -54 degrees Celsius (-65 degrees Fahrenheit). So far, Barbante, Chappellaz and their colleagues have collected cores of seven glaciers across Europe and one in Bolivia that will eventually be stored there, and they have plans underway for more international collaboration to add cores to the sanctuary from other parts of the world.

“We don’t want to lose these important archives,” said Barbante. “They give us a lot of information about the past of course, but also the present and the future.”

![]()

Andrea Spolaor remembers how far out the front of a tidewater glacier came when he visited the world’s first northernmost research station in Svalbard, Norway, more than 10 years ago. He estimated that it has retreated by nearly 2 miles since then. In April 2023, when Spolaor, a snow chemist at the Italian Research Council, led an expedition to take a core from an ice field 25 miles from the Ny-Alesund station, melting already posed a problem.

When he and his team reached their chosen location, they set up their drill and got to work executing their plans to extract two 400-foot-long ice cores. But after about 80 feet they pulled up water. At first they tried to drain what they thought was a small pocket of melt. “After, I don’t know, five or six hours,” Spolaor said, “I think we got three or four hundred gallons of water out.” They hit an aquifer. In 2005, a research team drilled through solid ice at the same location.

Spolaor and company moved uphill to try again. This meant thinner ice, but they still managed to take three cores from about 240 feet without hitting water again.

Then it was time to pack the samples, harness them on sleds behind their snowmobiles, and go back to the research station. As they approached the coast, they discovered that a river had formed meltwater while draining aquifers and taking cores. They had no choice but to wade through 100 meters of freezing, waist-high water to carry out each box. “It was a little annoying,” Spolaor said. “We spent four hours in the water to take out the samples.”

Spolaor’s team’s research camp on an expedition on Svalbard. Riccardo Selvatico for CNR and Ca’ Foscari University of Venice

Spolaor and his team plan to use a portion of the samples for their immediate research needs, building on studies they’ve done in the past to understand what the future holds for Svalbard and other places in the Arctic. They hope that the lower portion of their ice core will cover an era of unexpected warming that occurred about 1,000 years ago, which has the potential to tell us something about how the poles respond to sudden warming. The samples they don’t use for research today will go to the Ice Memory Sanctuary in the years and decades to come for other research teams with questions of their own.

![]()

As snow accumulates on a glacier, it slowly crushes and compacts what lies beneath. The snow first transitions to a porous substance called firn, before being completely pressed into ice. But the pores do not disappear. The ice is full of small air bubbles. “This makes the ice an absolutely unique archive,” said Margit Schwikowsi, an environmental chemist and chair of the scientific committee for the Ice Memory Foundation, the organization founded in 2021 to create the sanctuary. The bubbles offer a glimpse of ancient atmosphere. “There is no other archive, to my knowledge,” Schwikowski said, “where you have this direct preservation of old air.”

The archives they carry allow ice cores to serve as historical records printed in the form of molecules and aerosols. The cores are filled with stories of eruptions, wildfires, storms, plasticand of course climates. Oxygen isotopes tell scientists about global temperatures when the ice formed, while the air pockets reveal what greenhouse gases were present in the past. But, as Spolaor and Schwikowski both encountered in their own investigations, runoff from melting glaciers can erode or completely erase some of those climate signals as meltwater flows through the ice crystals. And it can happen quite suddenly.

This past January, both Spolaor and Schwikowski independently published studies that reached similar conclusions for different glaciers: In just a few years, melting has eroded a significant portion of the climate record that the glaciers once contained.

Although the papers by Spolaor and Schwikowski are among the first to document this loss as it happens, scientists have long known that it is a possibility. Glaciers have been melting rapidly for decades, and there’s a chance we already have reached a tipping point which will cause them to continue to disappear even if aggressive climate action is taken.

With these concerns growing, some experts are also considering more targeted measures to protect the world’s glaciers. Earlier this month, a group of scientists released a first-of-its-kind report calls for a “major initiative” over the coming decades to study techniques that could slow, stop or even reverse the melting of glaciers and mitigate the accompanying rise in sea levels. One example is some form of underwater curtains that would insulate ice shelves from warmer ocean water. Scientists and advocates still hold out hope that these types of interventions won’t be necessary—but, as with the Ice Memory Sanctuary, it’s a form of insurance to at least explore these possibilities now.

![]()

Much work remains to be done for Barbante, Schwikowski and their colleagues, including the finalization of a scientific steering committee to evaluate proposals for the use of ice cores from the sanctuary, with a view to one day handing the foundation over to a major international body such as UNESCO that has the resources to manage this scientific treasure trove.

The more immediate challenge is to find funds to carry out the expeditions, and to convince their international colleagues to undertake the logistical complications of collecting an extra sample or two to send to Antarctica – which could mean that the risks of expeditions which are already complex and dangerous are increased. But many researchers are willing to take the risk to ensure that future generations will have access to the same important information that fuels their own studies.

“When you lose that, you’ve lost a record of climate on Earth that can never be recovered,” Jones said. “There are many scientists who realize this, and have realized this for decades, who are making heroic efforts to recover this ice before it disappears forever.”

– Syris Valentine

More exposure

A parting shot

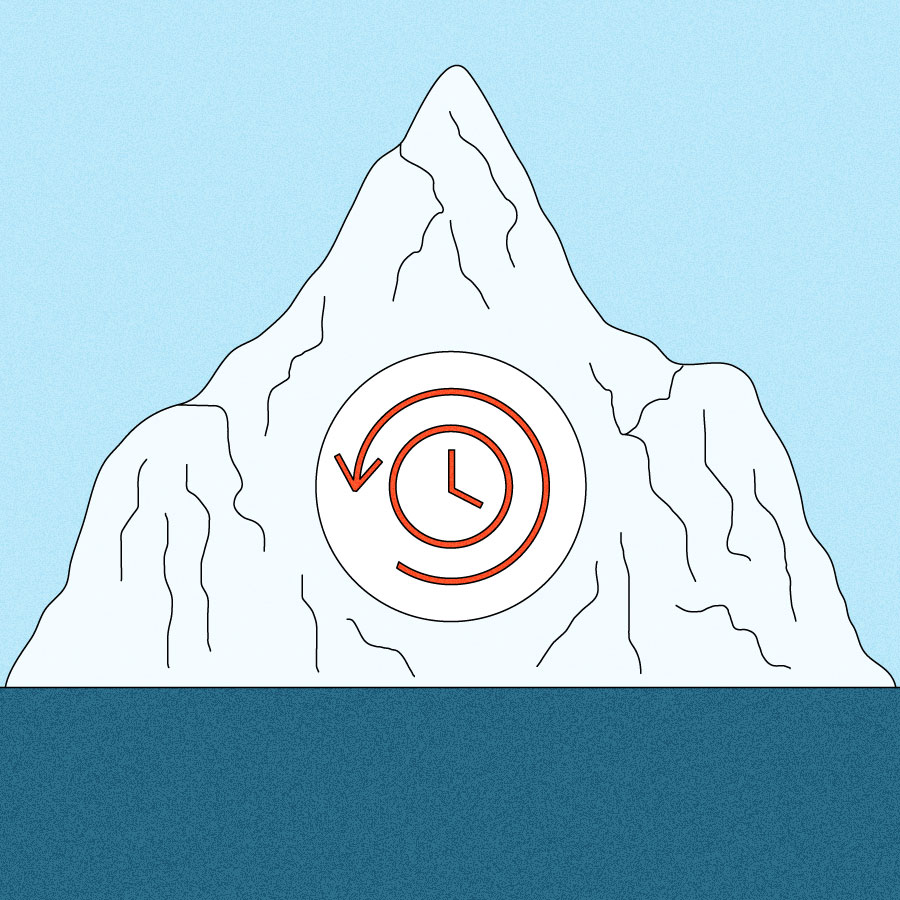

A photo of how ice samples are extracted. Here glaciologist Tobias Erhardt drills a shallow ice core at the East Greenland Ice Core Project camp.