Late on a Saturday afternoon in June 2022, Andrew Christ was on the verge of a discovery at the University of Vermont. A postdoctoral researcher studying the interactions between glaciers and landscapes at the time, Christ was flushing a sample taken from the bottom of a 30-year-old ice core from the center of the Greenland ice sheet – a mere 30 grams muddy slush left behind by glaciers grinding against the rock. As he watched, the sediment settled to the bottom of a plastic tub and small black specks began to float in the water.

“Oh my god, I’ve seen it before,” thought Christ. He observed a similar phenomenon in a sample from another location that his lab was investigating, but did not expect to see it in the middle of Greenland’s ice sheet. After peering at the specks through a microscope, he discovered they were fossilized fragments of ancient poppies, insect parts and tree bark – embodied memories of an ice-free Greenland, perfectly preserved in time.

This week, the University of Vermont team that analyzed this sample published a study concluded that the discovery of plant and insect life from the center of the continent indicates that at some point in the 1.1 million years the land contained hardly any ice, or perhaps none at all.

The new evidence that Greenland lived up to its green name in the not-so-distant past may represent an exciting scientific breakthrough, but it also heralds ominous possibilities for the future of humanity. Present-day atmospheric carbon dioxide levels are higher than they have been in millions of years; evidence of an ice-free Greenland in the more recent past means that it may take even less warming than previously expected to deplete the continent’s all-important ice sheet. The frozen fortress that covers Greenland contains enough fresh water to raise sea levels by 23 feet — a staggering volume that would reshape coastlines around the world.

As global temperatures exceed levels not seen for 125,000 years, that meltdown is already well underway. Since satellite records began in 1992, Antarctic and Arctic ice sheets have been staggering 7.5 trillion tons of ice combined. Less than a foot of sea-level rise since the turn of the century has already caused flooding in coastal communities around the world.

Predicting the future of ice sheets is a tough business. Scientists have not yet been able to make computer models that match the real-time melting they are observing, leaving the world’s governments unsure of how much sea level rise to prepare for. But as a growing body of evidence seems to suggest, what has melted once can melt again, leaving scientists concerned that Greenland’s ice sheet is vulnerable enough to disappear entirely.

“Studies like this are pretty rare because we just don’t have that much access to the bottom of the Greenland ice sheet,” Tyler Jones, a glacier science researcher at the University of Colorado, said of this week’s new research. (Jones was not involved in the University of Vermont paper, but he has studied temperature records in ice cores.) “This can really help us understand how it might behave in a future warmer world.”

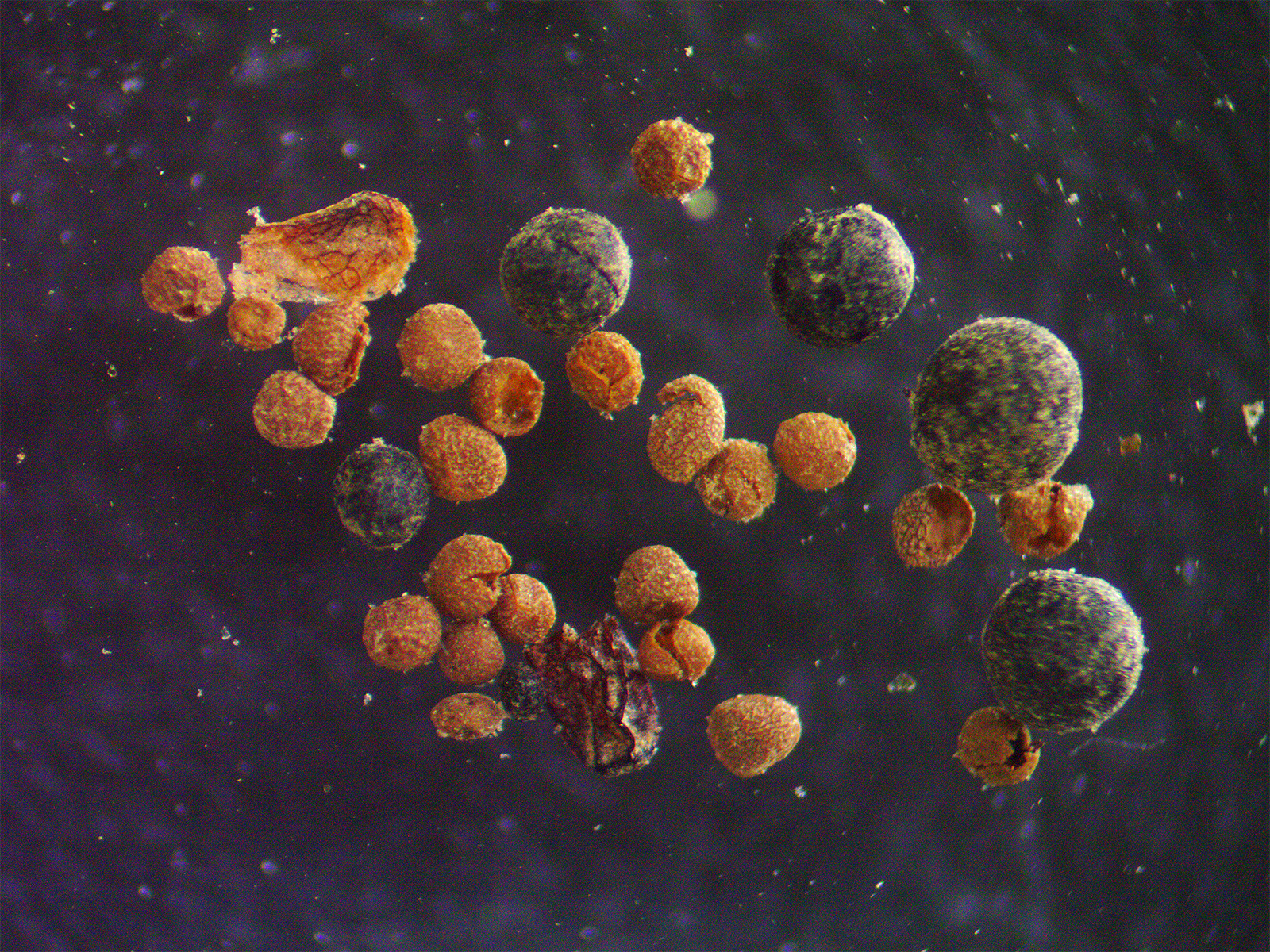

Halley Mastro / The University of Vermont

For their study, the University of Vermont team began by requesting a sample of the sediment where the 1993 Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2, or GISP2, ice core hit the rock—one of the few samples of its kind. It came from 2 miles below the ice and, along with the rest of the core, took five years of drilling to extract.

“Ice cores are amazing books, basically like an archive of Earth’s past,” said Halley Mastro, a graduate student who led the study with Paul Bierman, a geology professor at the University of Vermont and the author of a forthcoming book on Greenland ice loss. According to Mastro, scientists have historically searched ice cores for the clean ice, where crystalline bubbles trap gases and chemicals indicative of past climate conditions.

“But what we have is 8 centimeters of dirt from the bottom – it just wasn’t that big of a priority at the time,” she added.

Bierman thinks part of the reason his team was the first to find fossils is because ice core scientists are trained to look for chemical clues instead. But in 2019, while scouring the sediment from the bottom of a core from Camp Century, a 1960s ice sheet drilling site near the perimeter of the Greenland ice sheet, he saw familiar floating black spots.

“Not being trained as an ice core scientist, I worked on more sediment for the first 10 years of my career, and I knew how to find fossils,” Bierman said. “It was a completely happy moment.”

In 2021, Bierman and Christ published their findings from Camp Century. Then, in 2023, they did dated the fossilized vegetation they found up to just 416,000 years ago – suggesting that the edge of Greenland must have been ice-free at the time. Now, after finding fossils in the GISP2 core – which are evidence of a thriving tundra ecosystem also in central Greenland – Bierman and Mastro believe that the continent as a whole sometime in the last 1.1 million years at least 90 percent ice free. . As Mastro puts it, “No ice sheet will have a big hole in the middle.”

“If you find plants at the bottom, that means the ice is gone almost everywhere,” said Dorothy Peteet, a macrofossil expert who helped Mastro analyze the sample. The researchers found fragments of moss, fungus, a poppy seed, willow bark and an insect eye and legs. According to Peteet, the fragility of these types of specimens makes the discovery particularly remarkable: This means that as the glacier formed, it must not have moved much, or it would have destroyed these fragments when it ground against the rock.

For Peteet, the most exciting part of the discovery is the comparison with modern-day plants, and what they indicate about past climates. For example, the presence of poppy seeds could indicate that the continent enjoyed a balmy temperature average of about 40 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the paper.

“A certain fossil tells you that that plant was there, then you can really fingerprint the climate it grew in, based on a modern analogue today,” she said.

Jones, the University of Colorado glaciologist, said the new study points to the need for more research, given its potential implications for future ice loss.

“At some point we’re going to create a planet that’s warmer than any time in the last few million years,” he told Grist. “We are most likely creating a world where these ice sheets are going to melt.”

On the plus side, scientists may not have to wait another 30 years for more samples: Next year, a group of researchers from Denmark’s Center for Ice and Climate plan to return to an old ice core drilling site near the center of Greenland, just 19 miles from GISP2.

Meanwhile, according to Jones, the evidence points to an urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit planetary warming and sea level rise.

“Once you melt that Greenland ice sheet, it’s irreversible,” he said. “It won’t come back for a very, very, very long time.”