Hello and welcome to week three of State of Emergency, a limited-run newsletter about how disasters are reshaping our politics. I’m Jake Bittle.

Hurricane Michael ripped across the Florida Panhandle as a Category 5 storm less than four weeks before the pivotal 2018 midterm elections, killing dozens of people and destroying more than 1,000 structures. In the weeks following the storm, then-Governor Rick Scott issued an executive order that loosened restrictions around ballots and allowed local governments to open fewer polling places on Election Day.

“We do not find evidence that the amount of rainfall from the hurricane caused the turnout to decrease. We do find that the closing of polling stations and greater travel distances have significantly depressed the turnout.”

– Kevin Morris and Peter Miller, authors of “Authority after the Tempest: Hurricane Michael and the 2018 Elections”

A few years later, an academic study of voting rights in the wake of Michael reached a disturbing conclusion. “We find no evidence that the amount of rainfall from the hurricane caused the turnout drop” in the election, wrote the authorsbut “we do find that closing polls and greater travel distances have significantly reduced turnout.” With each additional mile voters had to drive, turnout rates decreased by as much as 1.1 percent. The election saw a larger share of voters in hurricane-ravaged counties cast their ballots by mail, but those who didn’t have time to request those ballots or vote early were left with few options on Election Day.

Two men stand next to a road destroyed during Hurricane Michael near Eastpoint, Florida on October 12, 2018.

Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images

The aftermath of a disaster can be terrifying and traumatic, and many victims struggle to obtain basic necessities such as food and shelter, or fill out paperwork for disaster relief and insurance. Finding accurate information about where and how to vote is even more difficult — so difficult, in fact, that many disaster survivors don’t bother to vote at all.

The US is in the middle of a historically busy hurricane seasonand wildfires are raging across the arid West, meaning there’s a high chance many communities will see climate disasters disrupt the normal voting process during this year’s election. These communities may also see confusion and misinformation about which elected representatives and branches of government are in charge of which aspects of disaster response, which can make it more difficult to hold public officials accountable for the recovery process.

As part of our state of emergency series, Grist, with the help of our senior manager of community engagement, Lyndsey Gilpin, is publishing two guides that will help vulnerable communities prepare for and navigate the increasingly common disasters. These guides are free to republish, share and distribute.

The first guide outline the process of disaster recovery, and explain which levels of government take charge of evacuation, relief and rebuilding. We explain who has the power to issue emergency declarations, who handles first-response duties during floods and fires, and who is in charge of distributing financial assistance to families and public institutions such as school boards.

The second covers how disasters can disrupt the voting process. Depending on where you live and what climate risks your community faces, one or more of the usual voting methods — postal voting, early voting and Election Day voting — may be difficult or impossible. This guide covers everything from the rules and deadlines for ordering an absentee ballot in disaster-prone states to outlining your options if you lose access to your ID or permanent residency in the weeks before an election.

Disasters are unpredictable, but staying prepared and informed can help you and your neighbors minimize the disruptions caused by extreme weather. We at Grist hope these guides help you do just that, and we encourage you to read and share them widely.

Red disaster, blue disaster

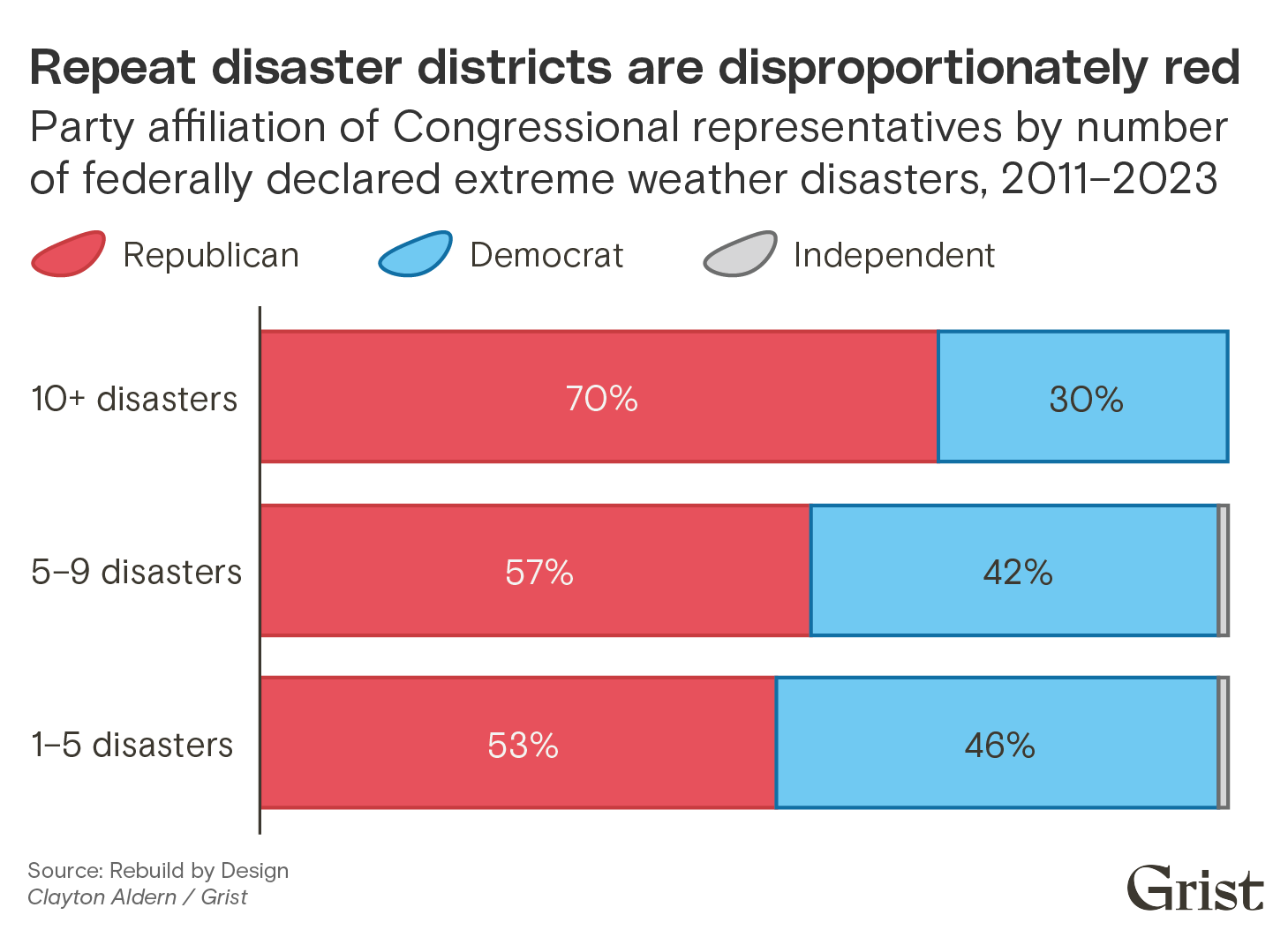

It’s a truism among emergency managers and disaster experts that no region or area is safe from disaster, but the places in the United States that have been hit hardest over the past decade are disproportionately Republican. New data from the climate resilience think tank Rebuild by Design shows that 70 percent of congressional districts that have seen 10 or more major disasters since 2011 are under Republican control. This trend is largely driven by districts in Appalachia and the Gulf Coast.

What we read

Do you mean it doesn’t pop balloons?: The landmark Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was one of the most ambitious climate laws ever passed in any country, but as my colleague Kate Yoder reports, most voters have no idea the law has anything to do with climate change, in part because of its rather misleading name. Read more

Read more

Check out ballot below: The reshuffled presidential election continues to dominate the news cycle, but a number of down-ballot races could be just as consequential for the climate, the New York Times reports in its Climate Forward newsletter. That includes a pair of public service commission elections in Arizona and Montana that could see utility regulators move to focus on building out more renewable energy. Read more

Read more

Houston votes on flood control spending: Voters in Harris County, Texas, will have their say on a property tax increase that will give $100 million to the county’s flood control district, allowing the agency to spend more money on retention ponds, flood channels and home buyouts in the notoriously storm-prone city. Read more

Read more

Post-Debby rage in Florida: Residents of Sarasota, Florida are outraged after new development in their area caused worsening flooding during Hurricane Debby earlier this month. They are seeking answers from two candidates vying for an open seat on the county commission. Read more

Read more

Maybe bring a pencil?: Michigan officials blame stormy weather for low turnout in the state’s recent primary elections. That’s not only because storms knocked out the power grid in some towns, but also because humid weather caused ballots to swell, making it difficult for tabulators to read ballots marked with ballpoint pens. Read more

Read more