The vision

“It doesn’t matter how many thermographs we have, boots on the ground, satellites flying in the sky, people with drones and airplanes and all the other technology, none of it matters if you don’t stop methane. None of that counts.”

— Sharon Wilson, “methane hunter” and director of Oilfield Witness

The spotlight

When I worked with satellites (my career before journalism), and I talked about my work with people outside the space industry, they often simply responded, “Oh, cool.” It has always struck me that while satellites make modern life possible in many ways, many people still think of space technology in terms of astronauts and other worlds. But satellites are what make GPS, weather forecasting, long-distance communications and even airplane Wi-Fi possible. And a growing fleet of precision satellites is now also enabling climate solutions: helping us track and stop pollution.

Two weeks ago, a satellite designed to identify, measure and monitor greenhouse gas emissions worldwide launched into orbit by SpaceX. The spacecraft, called Tanager-1, is a collaboration between NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Earth-imaging company Planet Labs, the environmental non-profit Carbon Mapper, and others. Tanager-1 has now joined 23 other satellites in orbit, operated by a mix of organizations and agencies, all capable of detecting the powerful greenhouse gas methane – which, for the first 20 years after it released, heats the planet 80 times faster than the same amount of CO2.

Naveena Sadasivam and I recently reported on this new wave of methane monitoring satellitesand as part of that reporting, we had the chance to speak with Riley Duren, the CEO of Carbon Mapper. Duren previously worked as the chief systems engineer for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Earth Science Division where he pushed to establish a climate research portfolio, which included expanding the laboratory’s ability to monitor greenhouse gases. He knew this monitoring could help mitigate climate change, not just study it.

“You can’t manage what you don’t measure,” said Duren.

Carbon Mapper itself emerged in 2020 as a “spin-off,” Duren said, of the work he and others at the lab did to study the sources of methane emissions from aircraft, identify the worst offenders and alerting them so that the operators can take action to fix the leaks that the researchers have noticed. Although they had a lot of success with these aerial surveillance campaigns, “to do it in a sustained and operational way,” Duren said, “we needed satellites.”

But government agencies had no plans to build and launch those kinds of satellites, so Duren began talking to climate philanthropists to raise the funds that would allow him and Carbon Mapper to create their own spacecraft.

Tanager-1, and the flock of similar satellites Carbon Mapper plans to launch, will work with another non-profit mission launched earlier this year, MethaneSAT, to better understand where the highest value actions can be taken to stem methane emissions and leaks. Duren used a metaphor of photographing birds to describe how the satellites could support each other’s efforts to monitor methane. MethaneSAT provides the equivalent of a landscape view, and can pinpoint where there is a flurry of bird activity. Tanager-1 can then zoom in and capture telephoto snapshots of the metaphorical birds and nests. “And because Carbon Mapper flies a constellation of satellites,” Duren said, “it’s kind of like an army of birders going out to follow up on what the landscape photographer caught everyone’s attention.”

Below is an excerpt from the feature I co-wrote with Naveena, covering the highly anticipated launch of MethaneSAT in March, and the hopes and concerns of those watching. You can find the full feature hereif you want to read more about the history of using satellites to monitor greenhouse gas emissions, what this new fleet offers, and what opportunities researchers hope to open up with this new and improved technology.

– Syris Valentine

![]()

Spying from space: How satellites can help identify and contain a powerful climate pollutant (Excerpt)

On a stormy day in early March, the who’s who of methane research gathered at the Vandenberg Space Force Base in Santa Barbara, California. Dozens of people crammed into a NASA mission control center. Others watched from cars that lined roads just outside the sprawling facility. Many more followed a live stream. They came from across the country to witness the launch of an oven-sized satellite capable of detecting the powerful planet-warming gas from space.

The amount of methane, the primary component in natural gas, in the atmosphere has risen steadily in recent decades, reaching nearly three times as much as in pre-industrial times. About a third of methane emissions in the United States occur during the extraction of fossil fuels as the gas seeps from wellheads, pipelines and other equipment. The rest comes from agricultural operations, landfills, coal mining and other sources. Some of these leaks are large enough to be seen from orbit. Others are few but add to a growing problem.

Identifying and repairing it is a relatively simple climate solution. Methane has a warming potential that is about 80 times higher than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period, so reducing the levels in the atmosphere can help combat global temperature rise. And unlike other industries where the technology to decarbonize is still relatively new, oil and gas companies have long had the tools and knowledge to fix these leaks.

MethaneSAT, the gas detection device launched in March, is the latest in a growing armada of satellites designed to detect methane. Led by the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund, or EDF, and more than six years in the making, the satellite has the ability to circle the globe 15 times a day and monitor regions where 80 percent of the world’s oil and gas are produced . Along with other satellites in orbit, it is expected to dramatically change how regulators and watchdogs police the oil and gas industry.

“Companies are doing a good job of complying with the law, but the law has been inadequate,” said Danielle Fugere, president and chief counsel at As You Sow, a nonprofit that has used shareholder advocacy to pressure fossil fuel producers to tackle climate change. . “So this change will increase incentives for reducing methane emissions.”

Those at Vandenberg or watching online were a little on edge. A lot can go wrong. The SpaceX rocket carrying the satellite into orbit may explode. A week earlier, engineers were worried about the device that holds the $88 million spacecraft in place during launch and pushes it into space. “It made us a little nervous,” recalls Steven Wofsy, an atmospheric scientist at Harvard University and a key architect of the project along with Steven Hamburg, the scientist who leads MethaneSAT at EDF. If it didn’t go wrong, the satellite could still fail to deploy or have trouble communicating with its keepers on Earth.

They need not worry. A few hours after the rocket exploded, Wofsy, Hamburg, and his colleagues watched on a television at a hotel about two miles away as their creation was ejected into orbit. It was a jubilant moment for members of the team, many of whom traveled to Vandenberg with their partners, parents and children. “Everyone spontaneously burst into cheers,” Wofsy said. “You [would’ve] thought your team scored a touchdown in overtime.”

The data the satellite generates in the coming months will be publicly accessible — available to environmental advocates, oil and gas companies and regulators. Everyone has a stake in the information that MethaneSAT will beam home. Climate advocates hope to use it to push for tighter regulations on methane emissions and to hold negligent operators accountable. Fossil fuel companies, many of which do their own monitoring, can use the information to detect and repair leaks, avoid fines, and recover a resource they can sell. Regulators can use the data to identify hotspots, develop targeted policies and catch polluters. For the first time, the Environmental Protection Agency is taking steps to use third-party data to enforce its air quality regulations, and is developing guidelines for using the intelligence satellites that MethaneSAT will provide. The satellite is so important to the agency’s efforts that EPA Administrator Michael Regan was in Santa Barbara for the launch, as was a congressional lawmaker. Activists viewed the satellite as a much-needed tool to address climate change.

“This is going to radically change the amount of empirically observed data that we have and greatly increase our understanding of the amount of methane emissions that are currently occurring and what needs to be done to reduce them,” says Dakota Raynes, a research and policy manager at the Environment -nonprofit organization Earthworks. “I’m hopeful that gaining that understanding will help continue to shift the narrative toward [the] phase out of fossil fuels.”

With the satellite safely orbiting 370 miles above Earth’s surface, the mission enters a critical second phase. In the coming months, EDF researchers will calibrate equipment and ensure that the satellite is working as planned. By next year, it is expected to transmit reams of information from around the world. Its success will depend on the quality of the data it can produce and – perhaps more importantly – how that data is used.

— Syris Valentine & Naveena Sadasivam

[Check out the full feature on the Grist site, here.]

More exposure

A parting shot

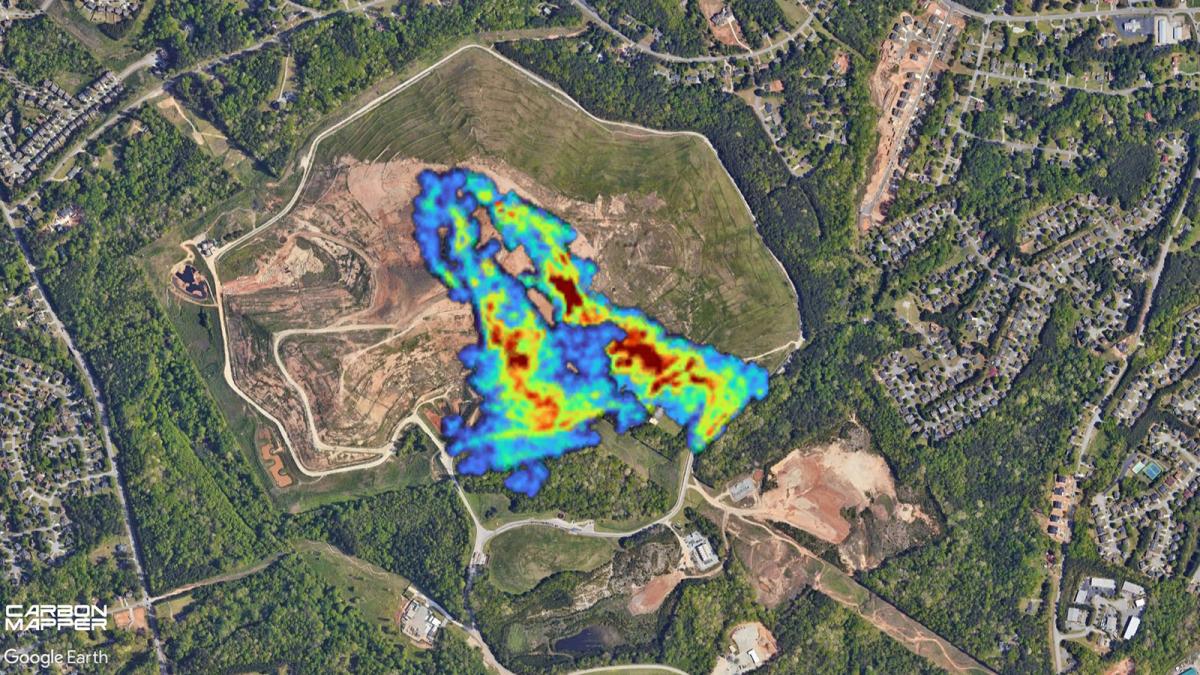

This image shows methane emissions from a landfill in Georgia, detected by Carbon Mapper’s airborne aerial surveillance (prior to the launch of Tanager-1, its first satellite). These imaging instruments use a spectrometer to reveal the infrared signature the gas leaves behind – making the invisible visible.

Methane is leaking from oil and gas infrastructure, including the Permian Basin in Texas, and landfills in Georgia and Louisiana.