When President Joe Biden nominated Deanne Criswell to serve as director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency in 2021, she received unanimous confirmation, a rare gesture of bipartisan support from the bitterly divided US Senate. A longtime firefighter who served overseas in the Colorado Air National Guard, Criswell also had decades of experience in emergency management, not only with FEMA, but in local emergency response leadership roles in Colorado and New York.

Criswell knew how the system worked at FEMA, but her mandate was to change the status quo at an agency often accused of being too slow to respond to disasters — and far too slow to adapt to climate change . In her three years leading the agency, she sought to overhaul FEMA’s disaster relief programs, oversaw billions of dollars in new spending on forward-looking adaptation projects, and navigated difficult disputes over the rising costs of insurance and rebuilding in vulnerable areas . Her goal was not only to ensure that FEMA runs well during disasters, but also to shift the agency’s culture, making it more responsive to survivors’ needs and more forward-looking about disaster preparedness.

With peak hurricane season approaching, Grist sat down with Criswell to discuss how she’s dealt with some of FEMA’s biggest challenges and how she’s sought to transform the agency from the inside. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q. Among communities hit by many disasters, FEMA has a reputation for indolence and bureaucracy. From your perspective, having both worked here and been a FEMA client, how much of that is earned?

A. We’ve heard this a lot, and I think that there are a lot of people who still have memories of Hurricane Katrina – they think of the FEMA of today as the FEMA of Katrina. We are a different team. We respond faster. We have more resources for recovery. We have more resources to help reduce impact, more resilience programs. We know that recovery is truly complex, and some communities are more complex than others. But recovery is doable, and so we need to work with a community to understand what their recovery needs are. We have these integrated recovery teams that go in and not only implement FEMA programs, but they help bring the whole space — federal agencies, philanthropies and nonprofits — together to help identify what that community’s recovery goals are and help them with those complicated road to recovery. While I think some of [the criticism] sometimes justified, I think we’re a very different agency than we were after Katrina, and we’re making big gains.

Q. Earlier this year, FEMA unveiled a set of reforms to its individual assistance programs, cutting red tape and offering survivors more money for food and housing after disasters. These reforms address many of the longest-standing complaints and criticisms about how that program works. Why didn’t this happen earlier?

A. We’ve been working on it since the day I came into this office. I think it really came about by listening to the people who are trying to get help and the struggles and the barriers that they face. I was a local emergency manager in a small community in Colorado. I was a local emergency manager in New York City. So I know what it’s like to be a customer of FEMA. In my very first year, I visited many of our joint field offices to hear from people and hear about the challenges they face.

I think that lens helps us keep that at the top of our priority list, and helps us focus on putting people first, and always trying to understand their barriers, and knowing that we’re not just a one-size-fits-all -pass- can’t have. all approach to the delivery of our programs. So I think a lot of it really has to do with the fact that we’ve had a lived experience of being on the other side.

Q. FEMA’s resilience programs allocate billions of dollars to climate adaptation and disaster preparedness. But much of the money from programs such as Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, or BRIC, go to white and rich areasand there is some “superuser” states who gets a lot of the money. I wonder what FEMA has done or can do to address those disparities.

A. When I came in, the first round of BRIC money was going out. Under a previous resilience program there was a cap of $5 million federal spending, and BRIC gave us a cap of $50 million, so people were very excited. But we saw from the first round that the structure we put in place was certainly not representative of all communities across America, and it really seemed to favor some of our coastal communities. So we’ve made adjustments each year to ensure that everyone has a fair chance in the competitive side of the program. We have direct technical assistance, which also makes a big impact – bringing in experts, especially for our most resourced communities who don’t necessarily have the expertise or the staff or the time to be able to think about the next mitigation [project] what they can do. We continue to expand it every year.

What I have now asked my team to do is to study the return on investment of resilience projects to see what works. We want to see projects succeed, and sometimes we see projects that don’t cross the finish line because of a poor start. We will continue to refine the way we score these projects to ensure that communities in greatest need get some of the benefit – for example, we add points to the score for new applicants, or if you are in a [vulnerable area].

Q. In response to protests from environmental groups and cities like Phoenix, which criticized FEMA for does not respond to heat wavesFEMA said it can only declare a disaster when state and local financial resources are exceeded. But few communities apply for heat disaster declarations because it is difficult to show how heat waves overwhelm local finances. Do you think FEMA can or should change its threshold for declaring a heat disaster? And if so, what can FEMA do to help residents during a heat wave?

A. I’m going to start with the preparedness side. We know heat comes every year, just like we know hurricanes come every year to the Gulf Coast and the East Coast. So the individual preparedness piece is very important, and we cannot deny that. We need people to know what their risk is, to know what kind of severe weather they are going to experience and what their personal needs are. If I know I have a condition that makes me more vulnerable to heat, what will I do during extremely hot days if my power goes out? We can also help reduce the impact through our mitigation programs – we have many communities using BRIC funding to plant tree canopies to reduce the impact of urban heat islands, or paint roofs white, or introduce splash pads for children . This reduces the overall impact.

But let’s go to emergency response. I was working in New York during Covid, and we were very concerned about the number of people who didn’t have air conditioning and the fact that we didn’t want to put them in communal settings. So New York City used money [from the federal housing department’s home energy assistance program LI-HEAP] to put air conditioners in people’s homes. From a cost perspective, if it was a disaster declaration, could FEMA have reimbursed the city for the air conditioners they put in? I don’t know. Maybe, but it also requires other agencies, doesn’t it? We need a whole-of-government solution to help these communities.

I think about what happened recently in Houston with Hurricane Beryl, and the power outages. What could we do or not do there? We can use some of our programs to maybe help individuals who are vulnerable to make sure they have a place to go, like a cooling center, or if it’s a long period of time and they need to move somewhere, maybe our programs can help We are not opposed to a state coming in and asking for a heat declaration. I just need to know what I’m compensating them for for it is not part of their normal budget. Some of the things I read are like, “we want FEMA to be able to pay for cooling centers.” Well, I don’t like the phrase “paying for a cooling center” because it makes it sound like I’m building something brand new, when really I’m just opening the library, or I’m letting people into the library.

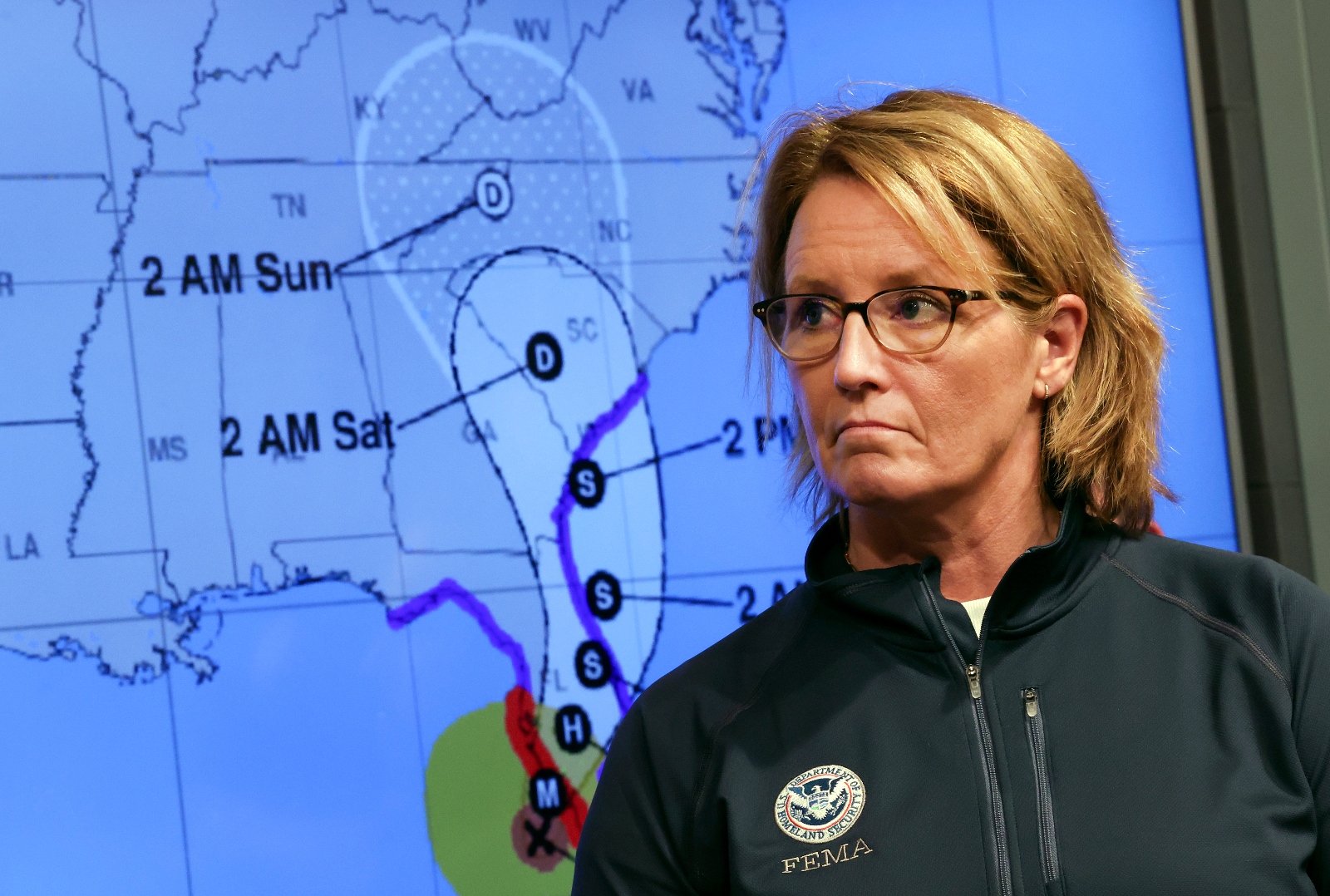

Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Q. Since Hurricane Ian hit Florida in 2022, I have heard about people trying to rebuild in Lee County that rising flood insurance costs are prohibitively expensive and rebuilding a house to code is very, very expensive – so much so that many people simply cannot afford it. To what extent is this the intended outcome of these programs – to discourage this kind of waterfront living? How much is this something that you think FEMA or Congress should try to address through affordability mechanisms?

A. I get asked all the time, “Should we allow people to rebuild there?” And in some areas I say probably not, which is why we have programs to help people buy and move. But most of the time it’s not a matter of where, it’s a matter of how. Looking at what’s going on in Lee County right now, we don’t want people rebuilding and putting their lives at risk. It’s not just about how much it will cost to rebuild that house: During Hurricane Ian, 150 people lost their lives. They were in houses that were not elevated high enough, or they chose not to evacuate.

So it’s not just about the cost of rebuilding, but also about: How do we do everything we can to protect lives in an area prone to a severe weather event? It’s about protecting lives and saving the people who live in those areas, and people will have to make personal choices about whether it’s the right place for them to live, based on what it’s going to require.

But to your last point about affordability [of flood insurance]we do believe that there are certain communities across the US that are definitely in an area that is high risk, but they got there through an environmental injustice—they’re low-income neighborhoods, but they’re high risk, and thus their cost is very high. We therefore believe an affordability plan is necessary to ensure that people can get the type of protection they need. But we also know that we have homes that are high value and high risk, and we’ve subsidized their rates before that.

Q. For the second year in a row, FEMA is short on money and Congress has not acted to supplement its budget. As a result, the agency had to implement once again “immediate needs funding,” meaning he paused almost all of his recovery and resilience projects and limited spending to emergency response operations only. With peak hurricane season approaching, what is the realistic worst-case scenario here, and what can FEMA do about it without action from Congress?

A. We have done immediate needs funding in the past, but it was usually after a major weather event caused us to spend the funds we had. What we find now is that we shut down Covid-19 [reimbursements]come in all those bills. We always want to make sure we have enough funding to support immediate responses to major incidents like Hurricane Ian, and we go into immediate needs when I reach a balance that will allow me to respond to one of those events. This is where we are now.

On the response side, I keep enough money to respond one event. As we watched Hurricane Debby, I was really worried because it was going to hit Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and beyond. If it had materialized as we thought it might, it could have used up the rest of the money I have available very quickly. There isn’t much I can do except get a supplement [appropriation] of Congress, and I’ve walked the halls of Congress to make sure they really know where we are – once I have that one big event, or maybe two events that come back to back, I’ll have to get back to them, and they may have to act faster than they planned.