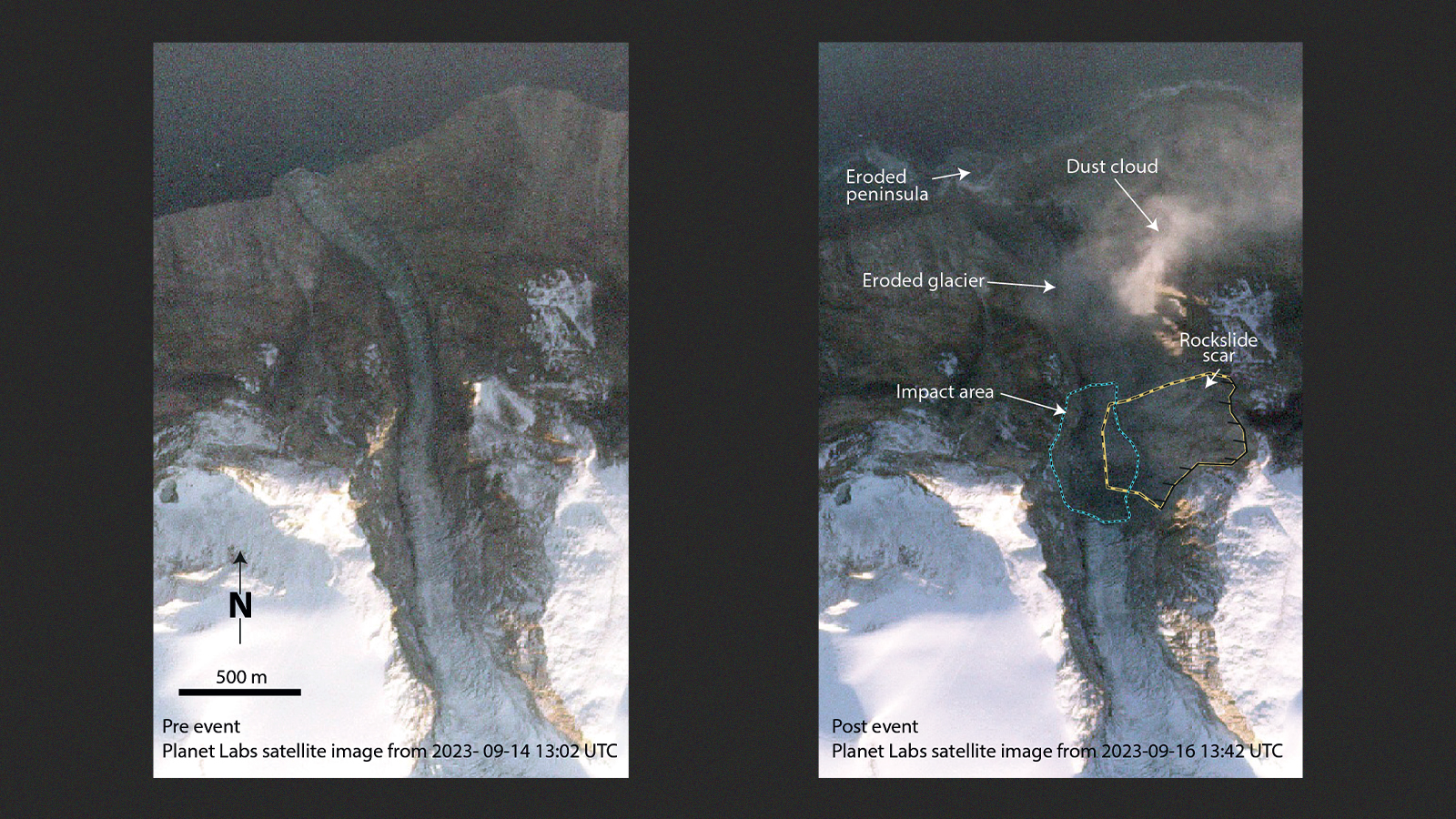

It was a warning shot picked up by seismometers around the world. Last September, a melting glacier collapsed, dislodging the mountaintop it supported into the Dicksonfjord in East Greenland. The impact produced a 650-foot-tall tsunami—twice the height of the Statue of Liberty—that crashed back and forth between the steep, narrow walls of the channel, rumbling so loudly that the vibrations sent the globe into a 90 -second interval wrist wrapped. for 9-straight days.

“It’s like a climate change alarm,” said Stephen Hicks, a seismologist at University College London. Hicks is part of an international team of researchers who finally figured out the source of the vibrations that have been a source of confusion since earthquake monitoring stations picked up the signal. Unraveling the mystery and mapping the tsunami took the team of 68 scientists, from a wide range of disciplines, a full year.

Planet Labs

The resulting paperrecently published in Science blames man-made global warming for the collapse. A century of greenhouse gases heating the atmosphere has eroded parts of the Greenland ice sheet — frozen freshwater that holds back 23 feet of potential sea-level rise. Hicks said this kind of landslide tsunami has never been seen in East Greenland, an area that tends to experience less melting than the country’s western perimeter. This could be a one-time, random event, or a sign of spreading instability. “We may expect more of these events in the future,” Hicks said.

Another group of researchers, from the University of Barcelona, recently confirmed the ice rink’s track. They studypublished in the Journal of Climate by the American Meteorological Society, found that days of extreme melting, linked to periods of warm, stagnant air in summer, have doubled in frequency and also intensified since 1950. About 40 percent of the ice that covers Greenland lost in a year during these extreme melting events.

“Each episode of melting is becoming more intense and frequent than in the past,” said Josep Bonsoms, a geography researcher at the University of Barcelona and the study’s lead author. For example, an extreme melt event in 2012 resulted in the loss of 610 gigatons of ice, enough to fill Lake Eerie, and then some.

According to the University of Barcelona researchers, even days of average melting, which are often influenced by the same weather conditions as extreme days, contribute to worsening melting in the future. Although their study did not make predictions, Bonsoms says the pattern is likely to continue to accelerate as the planet warms.

Take this summer. Greenland experienced above-average melting, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Centerbut not enough to be considered extreme. In July, two heat waves ate away the snowfall in the western region of the ice sheet, depleting its ability to reflect sunlight, known as albedo. When the darker glacial ice underneath was exposed, the land absorbed more heat, intensifying the melting.

On a larger scale, this type of feedback loop is one of the reasons why the region is warming four times faster than the rest of the planet, a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification. Tyler Jones, an Arctic researcher at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said that among the many catalysts driving Arctic strengthening, “the most important is the loss of sea ice.” Unlike Greenland’s land-bound ice, these floating patches of sea ice do not directly contribute to sea-level rise when they melt, but their albedo acts like a giant mirror that reflects the sun’s heat.

“If you remove that giant mirror, all of a sudden that incoming solar energy is absorbed by the ocean,” Jones said. Because the sea can trap and store so much heat, this means that the whole region gets warmer even in winter. The amount of sea ice remaining in September, the end of the annual melting season, has almost halved since the 1980s – with hardly any older than 4 years survive. This year, global sea ice levels have approached record lows.

“We are in a new climate regime. We’re seeing extremes that have just never been in our records of climate that are just now appearing in front of us,” Jones said. Because the melting itself continues, he says, the ice sheet will continue to destabilize until the damage is irreversible. And as sea levels continue to rise, coastal communities around the world will have to adapt to a new world of extremes for which their cities were not built.