When indigenous community organizer Jade BegayTesuque Pueblo and Diné, found out that Donald Trump had won the election in November 2016, she was on her way to Standing Rock of New Mexico to protest the Dakota Access pipeline.

The underground oil pipeline that snakes from North Dakota to Illinois has been the target of years of opposition by indigenous activists like Begay, who filed lawsuits against the pipeline and then resisted freezes and armed police to stop its construction after their legal challenges failed.

The strength of their resistance turned Standing Rock into an international symbol of indigenous activism and resistance. It inspired a new generation of Native American activists and helped create a 2016 victory by the US Army Corps of Engineers in the waning months of the Obama administration to delay the opening of the pipeline.

But the moment Begay learned of Trump’s victory, sitting in a ramen shop in Colorado on her way north from New Mexico, she realized the victory would be short-lived.

She was right. On January 24, 2017, just four days after his presidential inauguration, Donald Trump signed an executive order to speed up construction of the Dakota Access pipeline and pave the way for the 1,172-mile pipeline to go online just five months later. The decision set the tone for the Republican presidency: Indigenous peoples have repeatedly struggled to block decisions by the Trump administration that reversed decisions made under Obama.

Indigenous peoples have won some scattered victories: The Trump administration recognized seven tribesrepatriated Indigenous ancestral remains of Finlandand founded a task force on missing and murdered indigenous people. But his administration’s record on land and the environment has been one in which indigenous activists have often been on the defensive.

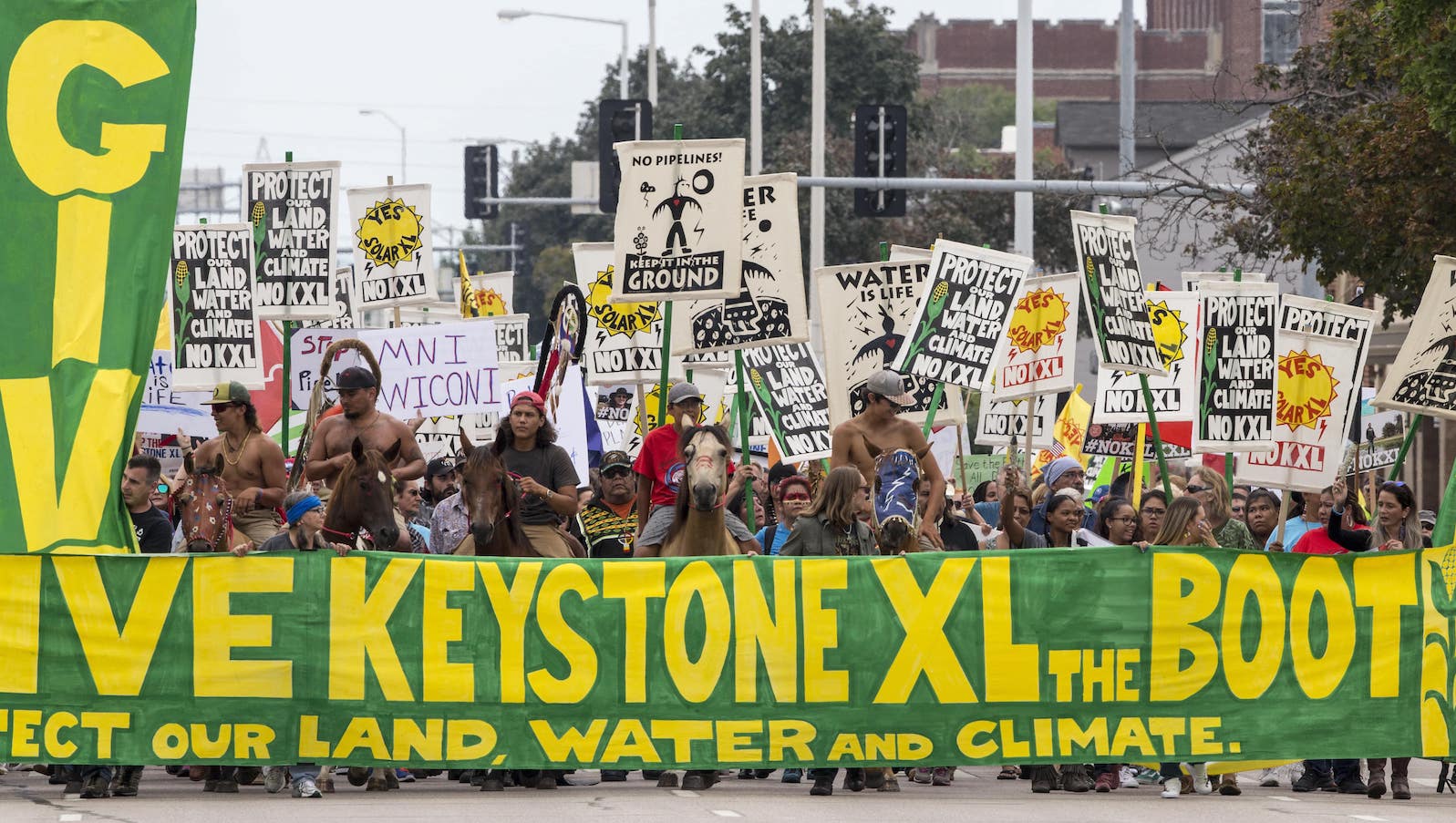

Trump rolled back the Bears Ears Monument by 85 percent to open the area to drilling, prompting lawsuits from indigenous-led groups. He pushed the Keystone XL pipeline forwardagain ignoring native opposition. He searched opening up parts of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for drilling despite opposition from indigenous groups such as the Gwich’in Steering Committee and Cultural Survival.

His border wall construction in Guadalupe Canyon, Arizona, has the Tohono O’odham Nation’s 10,000-year-old sacred burial ground. His administration attempted to remove land from the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe in New Englandthe first such move in several decades since the Termination Era during which the federal government tried to remove tribal lands and status.

“Working to protect tribal communities or indigenous communities during the Trump administration has been extremely difficult because the attacks have been constant,” Begay said.

Now that Trump is running for a second term, this time with Ohio Senator JD Vance at his side, Native Americans who lived through his first presidency say they expect a second one to mean more support for fossil fuel projects on reservations.

This could be good news for the small fraction of the more than 500 federally recognized tribes in the US that choose to allow fossil fuel mining on their lands. Daniel Cardenas of the National Stem Energy Association said he appreciates the Trump administration’s support for tribes that want to pursue oil and gas production, and thinks the Biden-Harris administration is too singularly focused on green energy.

But indigenous environmental advocates, such as Gussie Lord, a citizen of Oneida Nation and managing attorney of the Tribal Partnerships Program at Earth justicefelt overwhelmed during the Trump administration as they watched environmental regulations and commitments like the Paris Agreement fall away one after the other. For Lord, Trump’s first term was packed with “real backward-looking actions and a real backwards approach to tribal issues.”

In contrast, six days after taking office, President Joe Biden issued a memorandum requiring federal agencies to conduct meaningful consultation with tribal nations. While Trump’s funding for coronavirus relief initial funding for tribes delayed, the Biden-Harris administration incorporated them more fully into the creation of legislation and budgets, resulting in a 50 percent increase in funding for tribal lands compared to the previous four years under Trump.

“The last four years have been the most constructive in American history as it relates to the relationship between Native peoples and the United States government,” said Brian Schatz, the head of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, who helped to carry out the financing. Congress.

Larry Wright, the head of the National Congress of American Indianshope that whoever is elected in November continues some of the progress for Indian country made under the Biden-Harris administration, such as including indigenous knowledge in environmental reviews; proactively promote co-stewardship; and to set aside funding for tribes facing forced displacement due to climate change.

Trump hasn’t talked much about what he would do specifically regarding tribes in his next presidency. A spokesman for his campaign did not respond to a request for comment. The 16-page summary of the Republican platform on Trump’s campaign website does not contain the words “tribe”, “native” or “indigenous”. But it unequivocally spells out where Trump stands on energy projects.

“Common sense clearly tells us that we must unleash American energy if we are to destroy inflation and bring prices down rapidly, build the largest economy in history, revitalize our defense industrial base, fuel emerging industries, and maintain the United States as the manufacturing superpower wants to establish. of the world,” says the platform, all caps. “We will DRILL, BABY, DRILL and we will become energy independent and even dominant again.”

That commitment to fossil fuel production will surely deepen the climate crisis, harming indigenous people who are disproportionately likely to experience negative effects of climate change. Tribes living on reservations in the US are more susceptible to heat waves, wildfires and droughts than they would have been had they been allowed to remain on original lands.

Despite the Biden-Harris administration’s climate justice rhetoric, it has pursued fossil fuel production even more successfully than Trump’s has, and oil and gas production reached record highs.

Many Native Americans feel disillusioned by both parties. “It doesn’t matter who’s president, whether it’s a D or an R, they’re not our friends,” Cardenas said.

The Biden-Harris administration has also supported renewable extraction projects opposed by indigenous peoples, creating a $2 billion loan for a lithium mine at Thacker PassNevada, which is opposed by several tribal nations.

“There’s a lot of pressure on domestic sources of critical minerals, which was something that started under the Trump administration but continued under the Biden administration, and the Biden administration put a lot of money into it,” Lord van Earthjustice said, adding that this is a concern given the proximity of such minerals to indigenous lands.

The vast majority of minerals that are key to the energy transition are found within 35 miles of federal reserve landmeaning they are likely to be on ancestral lands taken from indigenous peoples.

Still, Lord said she was pleased with the Biden-Harris administration’s efforts to include tribal perspectives in their decision-making compared to the lack of input tribes had under the first Trump administration.

Schatz of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee thinks voters don’t have the luxury of voting third-party if they care about Native people.

“The difference is stark: One party wants to restore and cultivate self-determination, wants to provide resources for housing and education and health care and natural resource management. And the other party wants, at best, to ignore the tribes, and in many cases, through their right-wing legal machine, do violence to the foundation of tribal sovereignty,” he said.

Wright of the National Congress of American Indians said he understands why some tribal citizens may feel disillusioned. He suggests that rather than voting by party or abstaining, tribal citizens create a “sovereignty ticket” to support whichever candidates the tribes support more.

“Bad people get elected by indigenous people who don’t vote,” he said.

Editor’s note: Earthjustice is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers play no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.