Walk into the grocery store and look at the back of a container of food. Chances are you’ll see a little box with instructions on how to dispose of the packaging when you’re done with it: “empty and replace lid,” for example, or “recycle when clean and dry.”

These tags are made by How2Recyclea program run by the nonprofit GreenBlue, which they sell to more than 700 major food and consumer goods companies to dress up their products. The idea behind its creation was to alleviate confusion among consumers about what to do with all the boxes, jars, jugs and bottles in which their purchases were packaged.

In recent years, however, companies have come under scrutiny for being too liberal with their use of the iconic “chasing arrows” recycling symbol: It makes plastic bags and other products look more recyclable than they really are. Regulators have taken notice. At the national level is the Federal Trade Commission preparing an update of its “Green Guides”. for the use of sustainability labels, including the recycling symbol. And in California, state laws are expected limit the chase arrows for most packaging made from plastic, unless there is evidence that the plastic is being widely collected and turned into new products in the state. How2Recycle’s program, which was created to help clean up this mess, is also now under fire

GreenBlue announced earlier this month that it was revamping its more than decade-old How2Recycle labels. During a presentation at SPC Advance, a conference organized by one of GreenBlue’s subsidiaries, Paul Nowak, GreenBlue’s executive director, said the labels should “evolve with the world around us,” taking into account factors such as “policy” and “recycling rates.”

However, based on a sample image of the new labels, it is not clear whether GreenBlue’s updates will address concerns that they are tools for so-called greenwashing, or that they comply with state laws. Because there is no evidence that some of the products that will feature the new designs are actually recycled most of the time, the labels could violate California’s anti-deceptive advertising rules and put GreenBlue at risk of lawsuits from state regulators and consumer advocacy organizations.

The proposed labels are “an obvious and transparent attempt by the industry to circumvent California law,” said Howie Hirsch, a retired California attorney who has worked on several recycling-related misleading advertising lawsuits.

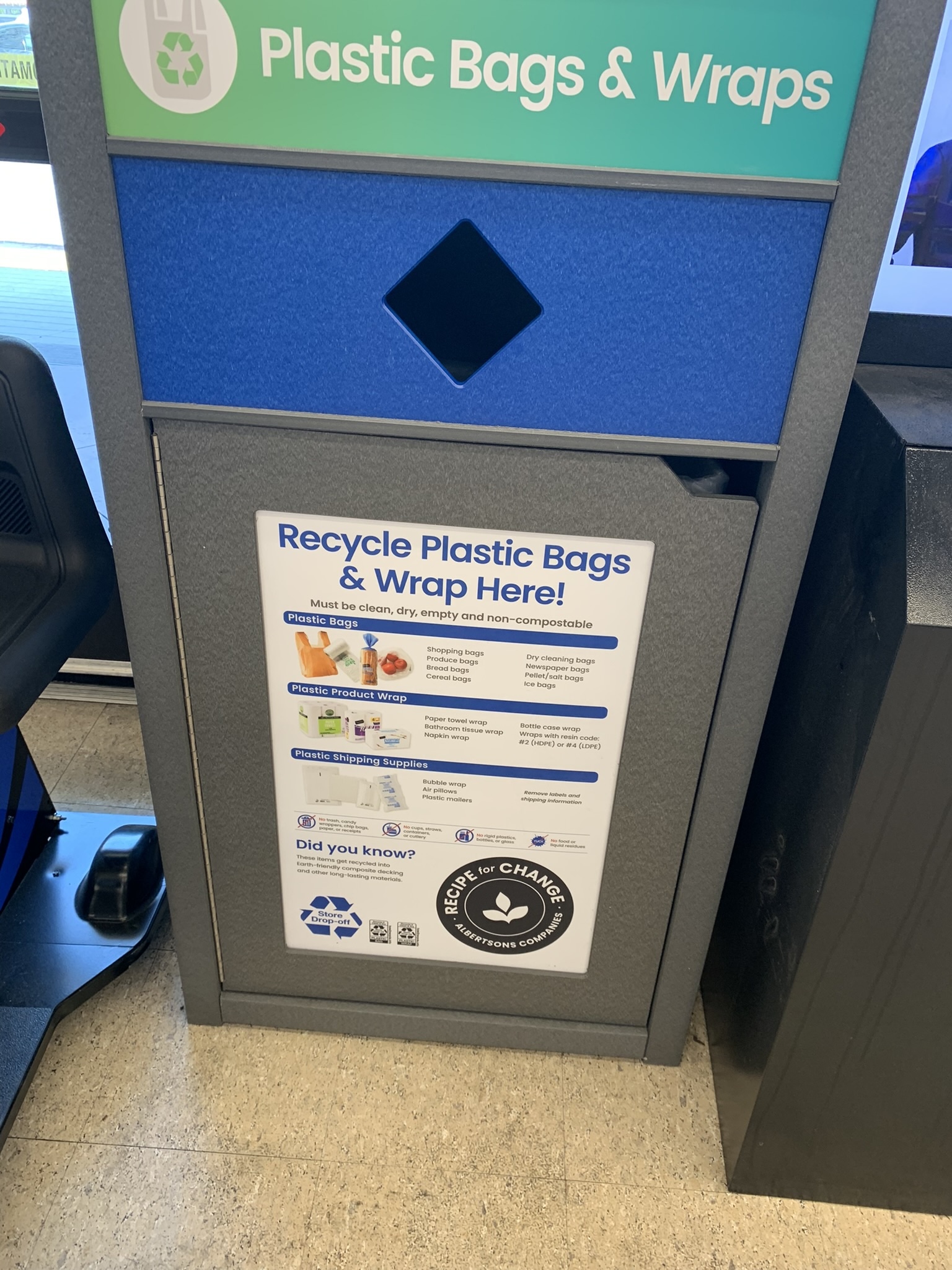

Hirsch specifically objects to GreenBlue’s “store drop-off” label, which instructs customers to deposit plastic bags in grocery store take-back bins so they can be picked up for recycling. Currently, this label contains the words “store pickup” within a triangular arrow symbol – giving the inaccurate impression that this plastic is likely to be recycled. A revised version of that tag, shared in Nowak’s presentation, simply changes the arrows’ path: Instead of chasing each other around a triangle, they now chase each other around a circle.

A store drop-off container for plastic bags and wrappers (left), and a packaging label with an older version of How2Recycle’s “store drop-off” label. Courtesy of JA Dell

According to Hirsch, that small change isn’t enough to comply with California law. First of all, one section of the California Business and Professions Code says that the darts triangle is functionally equivalent to – and subject to the same truth-in-labeling constraints as – the circular version proposed by GreenBlue. The law applies to any variant of the symbol that is “likely to be interpreted by a consumer as implying recyclability” — including “one or more arrows arranged in a circular pattern or around a globe.”

Another part of California law refers to the FTCs Green Guides require confirmation of recyclability claims: Companies that label their products with the chase arrows must provide proof that they are, in fact, widely collected for recycling and turned into new products within California. Plastic bag manufacturers have not provided such evidence, and they are be investigated from the California Attorney General’s office after failing to do so.

The circular chasers “seem to be just the kind of thing we were hoping to push back against,” said California state Sen. Ben Allen, a Democrat who sponsored landmark legislation to rein in the misleading use of the recycling symbol which became law. in 2022. A separate law passed last month will phase out plastic grocery bags offered to California shoppers at checkout. But many other types of plastic bags and thin film plastics will still be allowed.

Jan Dell, an independent chemical engineer and founder of the nonprofit The Last Beach Cleanup, would like to see How2Recycle’s store drop-off labels disappear entirely. Store Drop is “a hoax,” she told Grist via email. “All credible data, independent experts and many tracker studies prove that it is impossible to collect, sort and recycle post-household flexible plastic waste” on a meaningful scale.

According to an analysis conducted by Dell in 2020California only has the capacity to sort and recycle about 1 percent of its waste generated from plastic bags and film. Nationwide tracker studies of Bloomberg and ABC News – using Apple AirTags or similar devices – have shown that plastic bags dumped in store drop-off containers are more likely to end up in a landfill or incinerator than at a recycling facility.

Allen’s truth-in-labeling law will soon add even more specific requirements for the chase arrows and other symbols like it. Starting 18 months after the state’s recycling agency publishes a report on the recyclability of various materials, companies will have to show that products marked as recyclable through a non-fringe program – such as at a grocery store – at a rate of 60 percent or higher, and then sorted and recycled within the state. This threshold will rise to 75 percent in 2030.

Courtesy of Jan Dell

Recent analysis suggests that any type of plastic bag or film is unlikely to meet those high standards. In 2020, the Flexible Packaging Association said the US recycling rate for post-consumer film and flexible plastic packaging was just 2 percent. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a nonprofit that promotes a circular economy, estimates that “close to 0 percent” of flexible plastics sold to consumers around the world are recycled; the little recycling that does occur involves converting polyethylene film into “lower material quality applications” such as plastic sheeting and garbage bags.

“Once flexible packaging waste is generated, it is incredibly difficult to manage,” says the foundation’s report. As a first order of business, it recommends eliminating “unnecessary” plastic products.

In response to Grist’s request for comment, a spokesperson for GreenBlue said the organization is reviewing its proposal for new labels with government agencies, including the FTC and state attorneys general, “to ensure that linking the label’s symbol with additional clarifying information a thoroughly motivated claim.”

“If regulators deem the label to be inconsistent with California’s SB 343,” the spokesperson added, “How2Recycle will pursue a different label design.”

A spokesman for the California attorney general’s office declined to comment on the How2Recycle labels and would not confirm whether the office had spoken with GreenBlue. The FTC did not respond to Grist’s request for comment.

Allen, the California state senator, said the plastics industry’s time would be better spent redesigning products and eliminating unnecessary packaging to comply with recent laws, instead of fiddling with labels. In addition to the truth-in-labeling regulation, starting in 2022, California has a extended producer responsibility law which requires companies to meet increased recycling targets for certain types of products.

“If they have a real plan to fundamentally overhaul recycling in this space, then I’m interested in hearing about it,” Allen said. “But demanding recyclability or encouraging people to do something they know they’re never going to do in a meaningful way” – like dropping off bags at a store – “that’s greenwashing and it’s ‘ a joke, and I just don’t want us to allow it.