Hello, and welcome to our special Election Day edition of state of emergency. I’m Zoya Teirstein, and today I’m reporting from rainy Buncombe County, North Carolina. I spoke to voters that morning at the Fairview Public Library — one of 17 temporary polling places in the county set up after Hurricane Helene caused widespread damage in late September.

North Carolina is one of many states that experienced record-breaking early voting in the weeks leading up to Election Day — about 50 percent of registered voters in Buncombe, more than 115,000 people, cast ballots early, and local election officials expect a large turnout. turnout today if yes.

“The past four years have been brutal for small businesses. You come out of the grocery store with a couple of bags and it cost you $140 and you go, ‘What did I get? I took is what I got.’”

—Robert Lund, a home builder in his 50s, who said he was going to vote for Donald Trump.

Voting opened at 6:30 a.m. at Fairview Public Library, with dozens of people pouring in throughout the morning. While most are in the right place, a few voters accidentally ended up in the wrong place. “This is not my place,” one man called to me as he got back into his truck.

Sean Miller, a 26-year-old Democrat who lives in Fairview, lost almost all of her worldly possessions in Helene, and the road leading out of her community was destroyed. “We were trapped for a week,” she said, stopping to talk to me after casting her ballot. “And there was a tree in my house.” Miller was able to find her new polling place online once her power came back on.

The storm didn’t change who she planned to vote for, Miller said, but it deepened her conviction. “I really want to be able to keep the National Weather Service free and accessible to everyone,” she said, referring to A Project 2025 initiative to privatize federal weather data collection. “Helene didn’t change my opinion, but it made me feel more encouraged to vote to keep basic things that way.”

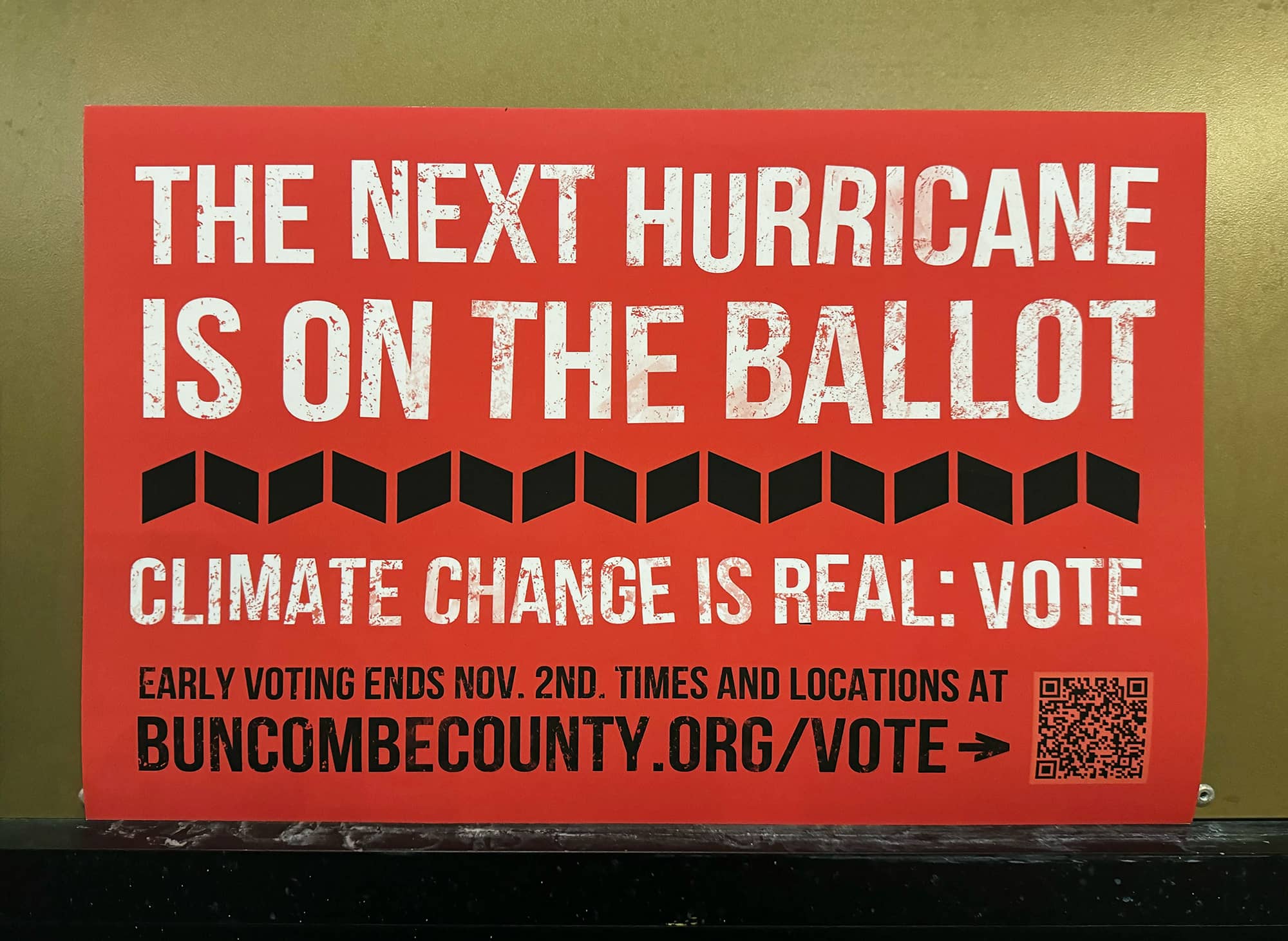

A sign at the Fairview Public Library polling place in Buncombe County, North Carolina.

Zoya Teirstein / Grist

Robert Lund, a home builder in his 50s, said he was initially worried the hurricane would affect his ability to vote, but he soon received information about this new polling place from the county. But like Miller, one thing the storm didn’t change was Lund’s politics. “The last four years have been brutal for small business,” he said on his way to the library. “You come out of the grocery store with a couple of bags and it costs you $140 and you go, ‘What did I get? I got taken is what I got.'” Lund said he was going to vote for Donald Trump.

Joining me in the field today are my colleagues Katie Myers, Grist’s embedded reporter at Blue Ridge Public Radio in western North Carolina, and Ayurella Horn-Muller, who reports from Florida in communities devastated by both Helene and hurricane milton. Go back with Grist later today for our Election Day broadcasts about how voters are feeling after the hurricane and the obstacles they faced trying to vote in the aftermath of a disaster.

A vulnerable Republican stakes his chair on water

Hello everyone, this is Jake. I’m across the country from Zoya, in California’s agriculturally rich Central Valley, but extreme weather is also affecting a critical election on this coast. This morning at Grist, I profiled David Valadaoa longtime congressman representing California’s 22nd District and one of the most vulnerable Republicans in the House of Representatives, where the GOP has a razor-thin margin of control. Valadao is a former dairy farmer who has spent his political career advocating for policies that provide more water for the agricultural industry — even when it means flouting environmental rules. Valadao’s district has suffered a historic drought in the decade since he entered Congress, and local farmers are strongly supporting him again this election cycle.

“Whoever is considered more likely to protect agriculture, or ensure existing water supplies and identify new ones, will be rewarded at the ballot box.”

—Tal Eslick, political consultant and former staffer of David Valadao

But the Central Valley is also home to many rural communities that lack reliable access to clean drinking water, and groups supporting his Democratic opponent, Rudy Salas, are trying to rally these low-income Hispanic communities to vote Valadao out. . They knocked on tens of thousands of doors in a district that last saw Valadao elected by just over 3,000 votes. The complex tangle of water politics in California rarely makes national headlines, but it could decide who ends up in control of Congress this year.

Read my full story on Valadao here.

What we read

Will climate voters show up?: The presidential election will likely come down to a few thousand votes in critical battleground states like Georgia. Our Grist colleagues Kate Yoder and Sachi Kitajima Mulkey look at the new efforts by advocacy groups and campaign volunteers to contact registered voters who care about climate change but rarely show up at the polls, urging them to cast their ballots. week.  Read more

Read more

Great Tuning Energy Races: Just 200 public officials have major control over the fate of the nation’s clean energy transition — and many of them are on your ballot this November. Grist reporters Emily Jones and Gautama Mehta take a look at the role state public service commissions play in regulating utilities, and the critical political races voters decide this year that could affect the deployment of clean power. Read more

Read more

What the election means for plastic: The United States is one of the world’s leading producers of plastics, and the next president could play a make-or-break role in addressing this crisis, according to my Grist colleague Joseph Winters. It will be up to the next administration to decide whether to push for limits on plastic production, as Biden has promised to do, or to renege on that commitment and let the industry produce as much as it wants. Read more

Read more

Raphael approaches: A tropical storm system named Rafael is forming in the Caribbean Sea and could become a hurricane later today, Election Day. The storm won’t disrupt the voting process, but it will likely make landfall somewhere around Louisiana this weekend, presenting the lame-duck Biden administration with another disaster challenge. Read more

Read more

Anger over floods in Spain: Protesters threw mud at the king and queen of Spain at the weekend during their royal visit to the site of unprecedented flooding in the Valencia region. The disaster killed more than 200 people and sparked anger from residents, who accused the government of waiting too long to send out emergency warnings. Read more

Read more