Tucked away in the most extreme nooks and crannies of Earth are biodiverse galaxies of microorganisms—some that may be able to help scour the atmosphere of the carbon dioxide humanity has pumped into it.

One microorganism in particular has caught scientists’ attention. UTEX 3222, nicknamed “Chonkus” for the way it swallows carbon dioxide, is a previously unknown cyanobacterium found in volcanic ocean vents. A recent newspaper in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology found it to boast exceptional atmosphere-cleaning potential—even among its well-studied peers. If scientists can figure out how to genetically engineer it, this single-celled organism’s natural quirks could be supercharged into a low-waste carbon capture system.

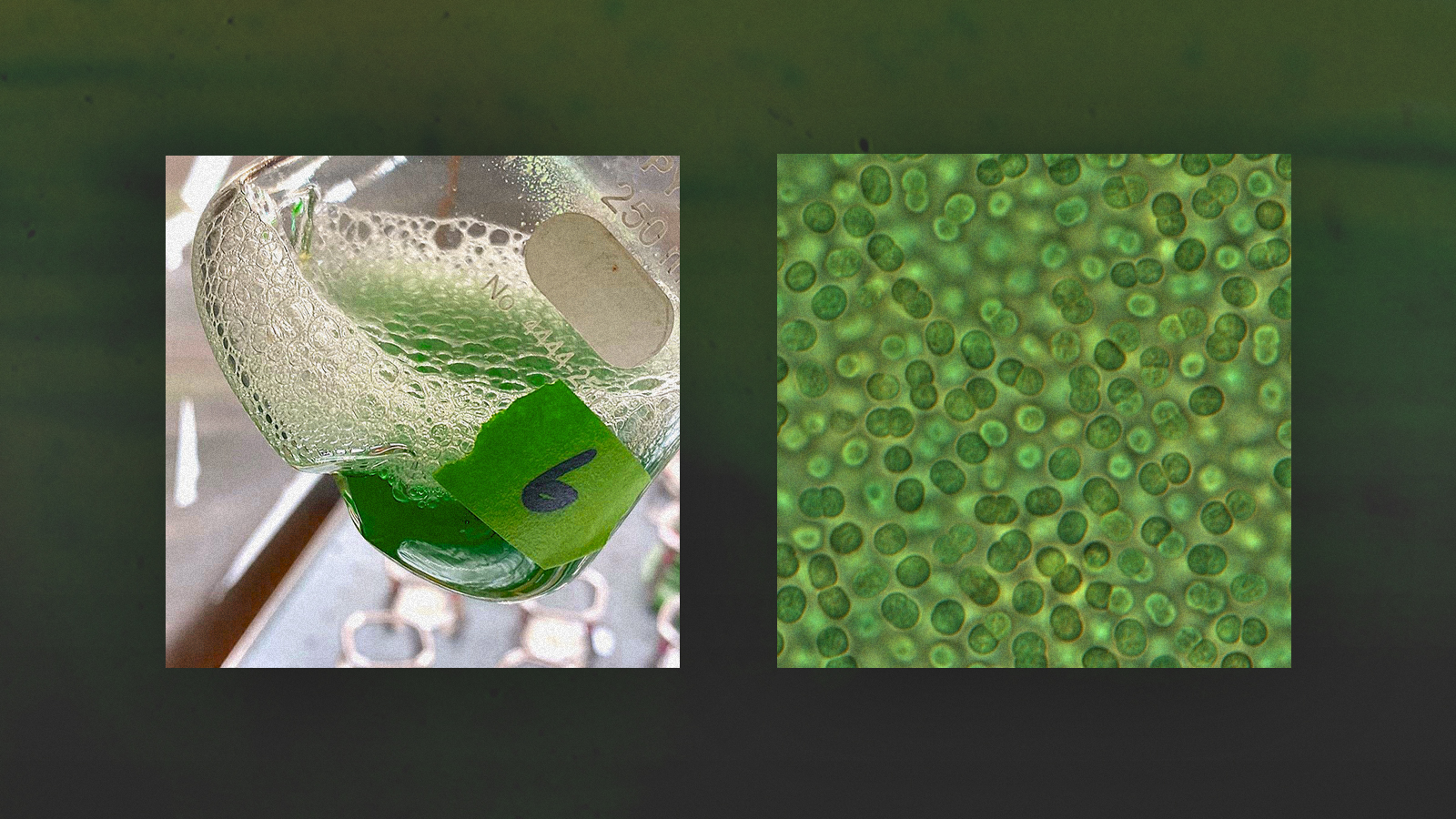

Cyanobacteria such as Chonkus, sometimes referred to by the misnomer blue-green algae, are aquatic organisms that, absorbs light and carbon dioxide and turns them into foodphotosynthesize like plants. But hidden within their unicellular bodies are compartments that enable them to concentrate and gobble up more CO2 than their distant leafy relatives. When found in exotic environments, they can develop unique characteristics not often found in the wild. For microorganism researchers, whose field has long revolved around a handful of easily managed organisms such as yeast and E. coli, the untapped biodiversity heralds new possibilities.

“There is more and more excitement about isolating new organisms,” said Braden Tierney, a microbiologist and one of the lead authors of the paper that identified Chonkus. On an expedition in September 2022, Tierney and researchers from the University of Palermo in Italy dove into the waters around Vulcano, an island off the coast of Sicily where volcanic vents in shallow water provide an unusual habitat – illuminated by sunlight and yet rich in plumes of carbon dioxide. The location produced a veritable soup of microbial life, including Chonkus.

John Kowitz / Two Frontiers

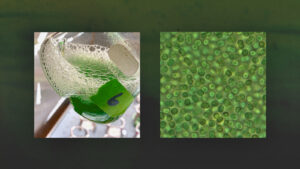

After Tierney obtained flasks of the seawater, Max Schubert, the other lead author of the cyanobacteria paper and a principal project scientist at the science nonprofit Align to Innovate, began working to identify the different organisms in them. Schubert said that in the open sea, cyanobacteria such as Chonkus grow slowly and are thinly distributed. “But if we wanted to use them to pull down carbon dioxide, we’d want them to grow much faster,” he said, “and grow in concentrations that don’t exist in the open ocean.”

Back in the lab, Chonkus did just that – growing faster and thicker than others previously discovered cyanobacteria candidates for carbon capture systems. “When you grow a culture of bacteria, it looks like broth and the bacteria are very diluted in the culture,” Schubert said, “but we found that Chonkus would settle into this stuff that’s much denser, like a green peanut butter.”

Chonkus’ peanut butter consistency is important to the breed’s potential in green biotechnology. Typically, biotech industries that use cyanobacteria and algae must separate them from the water in which they grow. Because Chonkus naturally does this by gravity, Schubert says, it can make the process more efficient. But there are many other mysteries to solve before a discovery like Chonkus can be used for carbon sequestration.

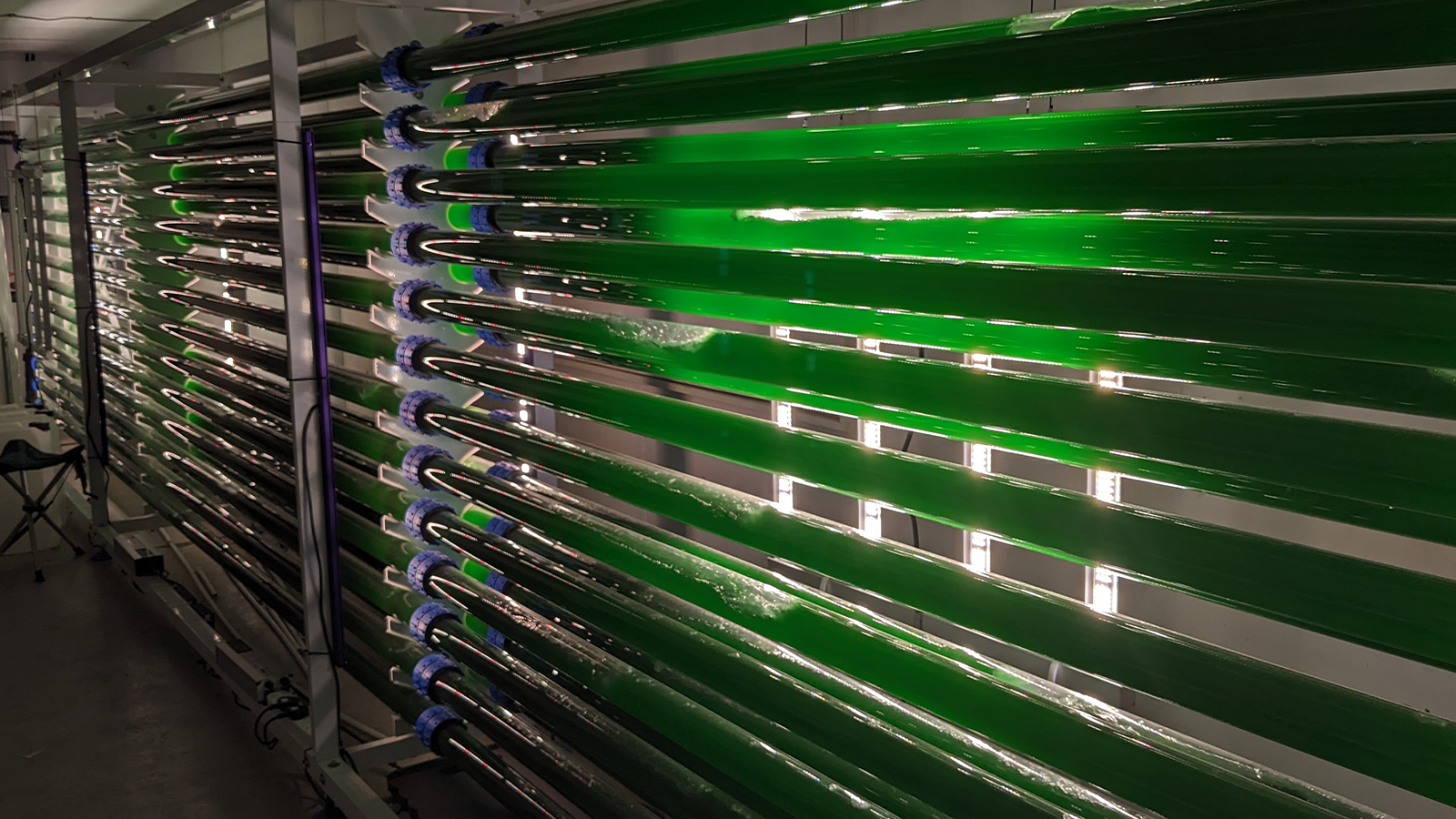

CyanoCaptureA UK-based cyanobacteria carbon capture company has developed a low-cost method of capturing carbon dioxide that runs on biomass, housing algae and cyanobacteria in clear tubes where they can grow and filter CO2. Although Chonkus shows unique promise, David Kim, the company’s CEO and founder, said biotech companies need to have more control over its properties, such as carbon storage, to use it successfully, and that requires finding a way to unlock its DNA. to crack

CyanoCapture

“Often in nature we’ll find that a microbe can do something cool, but it doesn’t do it as well as we should,” says Henry Lee, CEO of Cultivara non-profit biotech startup in Watertown, Massachusetts that specializes in genetic engineering of microbes. Cultivarium worked with CyanoCapture to help them study Chonkus, but have yet to figure out how to tamper with its DNA and improve its carbon capture properties. “Everybody wants to juice it up and adjust,” he said.

Since the expedition to Vulcano where Tierney started Chonkus, the nonprofit he founded to explore more extreme environments around the world, the Two Borders projectalso sampled hot springs in Colorado, volcanic chimneys in the Tyrrhenian Sea near Italy, and coral reefs in the Red Sea. Maybe out there, researchers will find a larger Chonkus that can store even more carbon, microbes that can help regrow corals, or more organisms that can ease the pains of a rapidly warming world. “There is no doubt that we will continue to find really, really interesting biology in these vents,” Tierney said. “I can’t stress enough that this was just the first expedition.”

Kim noted that less than 0.01 percent of all the microbes out there have been studied. “They do not represent the true arsenal of microbes that we can potentially work with to achieve humanity’s goals.”