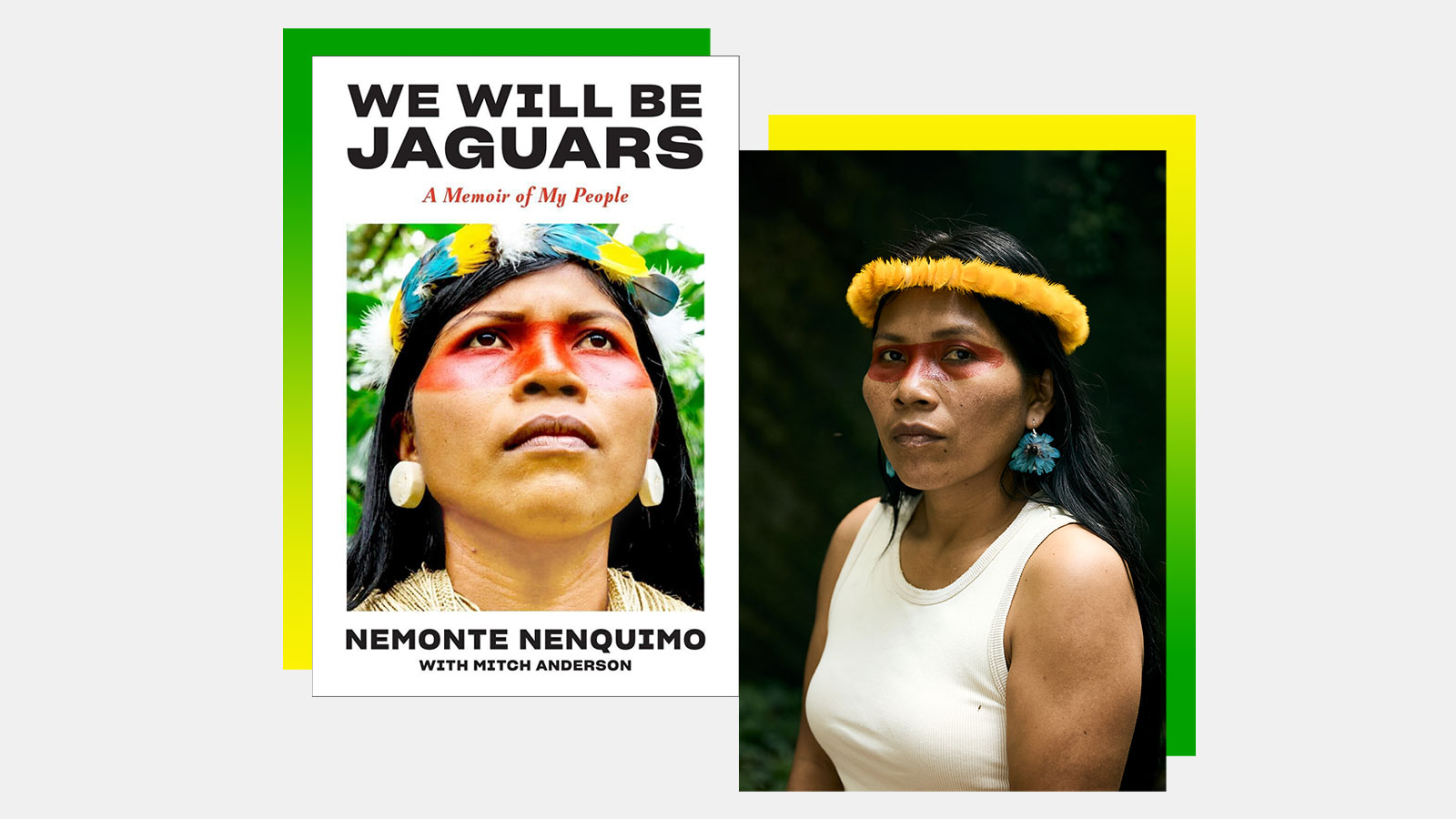

Nemonte Nenquimo was only 6 years old when she heard the hum of a plane overhead bringing white people to her village in the Amazon. Nenquimo is indigenous Waorami, and she has spent the last decade of her life fighting the efforts of oil companies to drill on her land.

She achieved enormous success: She led a lawsuit against planned oil drilling and won protecting half a million hectares of Amazon rainforest. She helped push for a national referendum to ban oil drilling in Yasuni National Park in Ecuador, which won resoundingly. Her work too set a legal precedent defense of indigenous rights.

This fall, she released a memoir called “We’ll be Jaguars,” chronicling her life story. The book has just been named this month’s choice for actress Reese Witherspoon’s book club. Nenquimo also continues to fight Ecuador’s President Daniel Noboa’s efforts continue oil extraction.

Grist spoke with Nenquimo to learn more about her work. Her responses were translated from Spanish and summarized for clarity.

Q. How does climate change affect your people?

A. The trees that usually bear fruit that feed and nourish the monkeys do not bear fruit, and the monkeys are now raiding the gardens of the town. Due to changes in the seasons, the river turtles do not find the right time to lay eggs on the beaches. My people notice very small and important changes in their ecosystem that the rest of the world does not understand. The rest of the world needs big hurricanes or big floods to think: ‘This is the climate crisis.’ But my father always told me that the climate crisis is the language of Mother Earth. This is Ma’s way of communicating with the people about what she experiences, how she changes, what she suffers.

Everyone talks about the urgency of the climate crisis, but it’s really only the world leaders and the business leaders who are in the rooms and making decisions. There is not really a true understanding that indigenous peoples and local communities are on the front lines stewarding and protecting their lands. They must not only be involved in seats at the table, but must lead and steer those conversations.

Q. Can you tell us more about your impression of those international climate talks and their connection to what is happening in your home country?

A. I was at COP and saw that there were indigenous leaders who were there, but they were there without spaces to speak. They traveled very far, but they couldn’t really get into the conference. And at the same time, it was a space where almost 200 countries entered into an agreement to switch away from fossil fuels. And when I returned to the Amazon, the first thing I saw in the Amazon was my government, which had agreed to transition away from fossil fuels, double oil, and make plans for another oil auction across the to launch south central Amazon.

It just confirmed that in the climate conferences it is still a colonial structure where world leaders and governments and businesses are the ones who steer the conversation and make decisions. Many of the promises are false promises. I am very convinced that world leaders and the economic system are hell-bent on continuing to extract oil as long as they can extract oil.

Q. What lessons do you think other indigenous activists can take away from your advocacy?

A. First, it is important to dream with your people, and to really build a vision for many generations of your people, because ultimately to win and confront the forces that threaten our lands and our livelihoods, we must unite be and we must be a powerful collective, and it starts with really listening and building a strong vision and a strong dream for your community and the people.

The second advice I would give to young indigenous activists is to focus on your own spirituality and your own connection with the earth and with your culture and with your territory, because we carry a lot of trauma. The world is very confusing and the world is very powerful and it’s easy to get wrapped up and sucked up, swept up, spat out by the world outside of your realms. And so really having a strong spiritual foundation and spiritual fortitude is a very powerful and important component to being a powerful and successful native warrior.

And then finally, to really try to build honest, authentic and powerful collaborations with non-Indigenous people, not to allow and allow outsiders to design and lead and suggest top-down solutions , but to really look for the utilization and building of real true cooperation with people from outside your area or Western organizations and activists. Really make sure they are committed to listening and learning and respecting your vision, your dreams and your rhythms.

Q. What tools would you say have been critical to your success so far?

A. First of all, using our rights – our international rights to require informed consent, our right to decide what happens in our territories – has been a very powerful strategy to protect our countries because we have the government’s designs on our territories and their efforts to auction could challenge. from our countries without our permission.

At the same time, we had to use communication strategies and social media and networks of allies, including celebrities, indigenous rights experts and people from around the world to support us, stand in solidarity with us and shine a spotlight on the justice system. to ensure that we can protect the outcome and protect the integrity of the process.

Also, building the capacity of indigenous organizations to manage resources is another important tool, for protecting our homelands and really building and designing strategies that work for us.

And then finally it was the utilization of new technologies and their combination with our own people’s knowledge and wisdom of our own forests and our territories. The governments and the companies tend to see our homelands as just a place to extract resources, our homelands as commodities, as almost kind of empty places waiting to be turned into productive zones, when in fact our territories are a complex web of life is what sustains our cultures and it sustains our planet’s climate and biodiversity. And so we created intricate territorial maps using new technologies, walking in the forests with the elders and the youth to tell the story of our land and finally show that our land is ours and to deeply provide the rights we already have to decide what happens in our country.

Q. What prompted you to write your book?

A. My people come from a long tradition of oral storytelling passed down through the generations for centuries. But the reason I decided to write a book was because we worked for many years to build a movement to protect indigenous territories and cultures from extraction violence and from conquest and colonialism, and achieved many important victories, but the threats keep coming. My father said the elders always say that the outsiders always destroy what they don’t understand and that the story dies if no one tells it.

This is an important time for me to write my story and that it is not outside people telling the story, but my own voice and as a way to create an opportunity for the outside world to learn about me people and the connection they have. the ground. Because the people who come from outside either destroy what they don’t understand or they try to help what they don’t understand. And either way, they cause harm.

And it was also an attempt to create a story that the Waorami children could listen to, and feel proud of.

Q. As you continue to fight oil drilling in your areas, how would you characterize what is at stake?

A. Life is at stake. Our culture, our knowledge, our connection with the land and water, the forest, the wildlife. Ultimately, if the governments and the companies achieve what they want to achieve, which is the destruction of our cultures and of our countries, they will also create a worsening climate crisis and cause these tipping points around the world. And what I’m trying to do is share my story and my people’s story with the world, to wake the world up so they can understand that what’s at stake is life itself and that if we continue to build economies based on infinite growth and endless consumption then we are going to destroy the very Mother who gives us life.

I really believe in the power of the people and civil society and citizens around the world to wake up and realize the stakes of the climate crisis and realize that action needs to happen now and in their own communities. It starts with each of us in our communities building community, building the power to change the system.