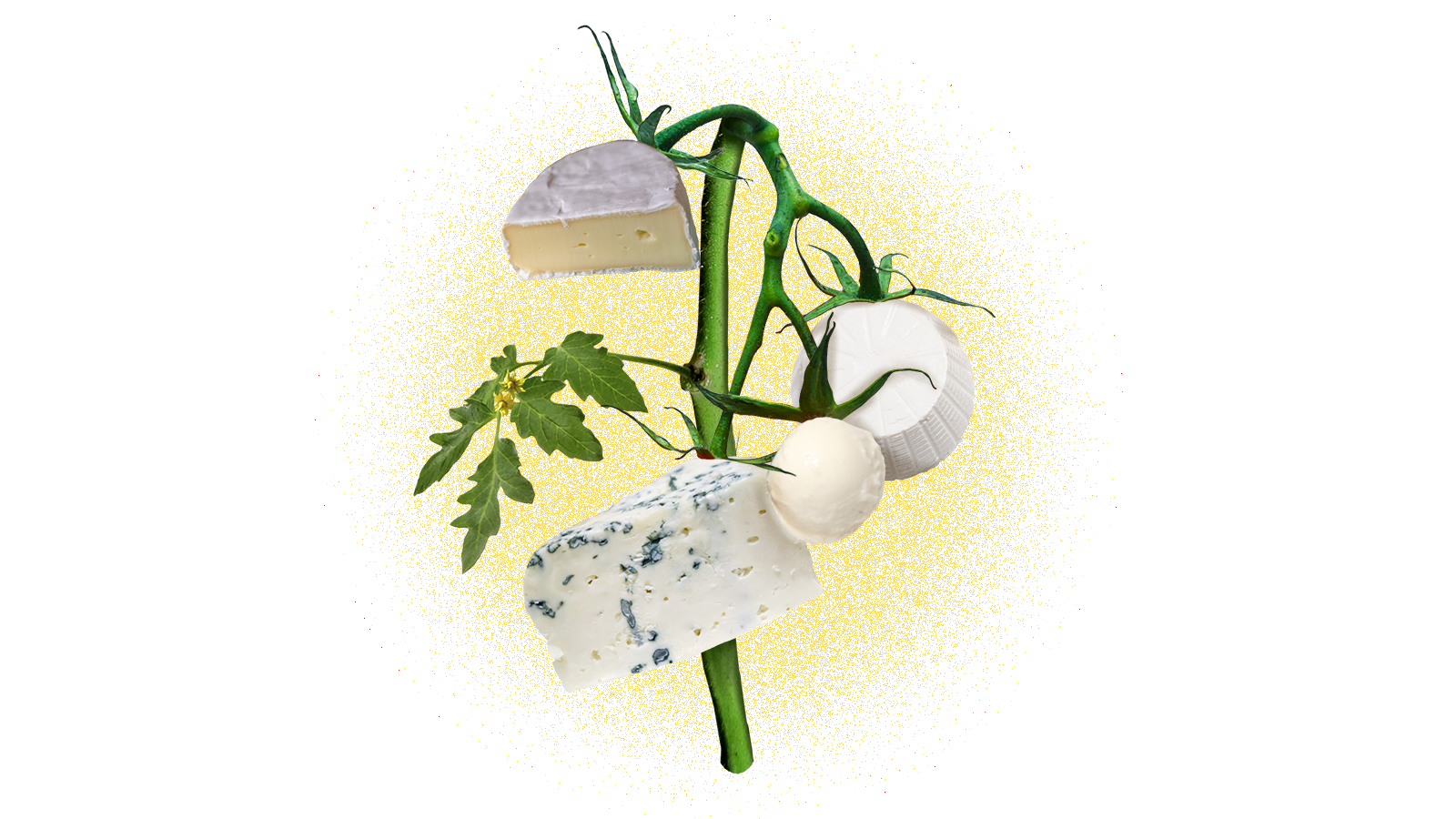

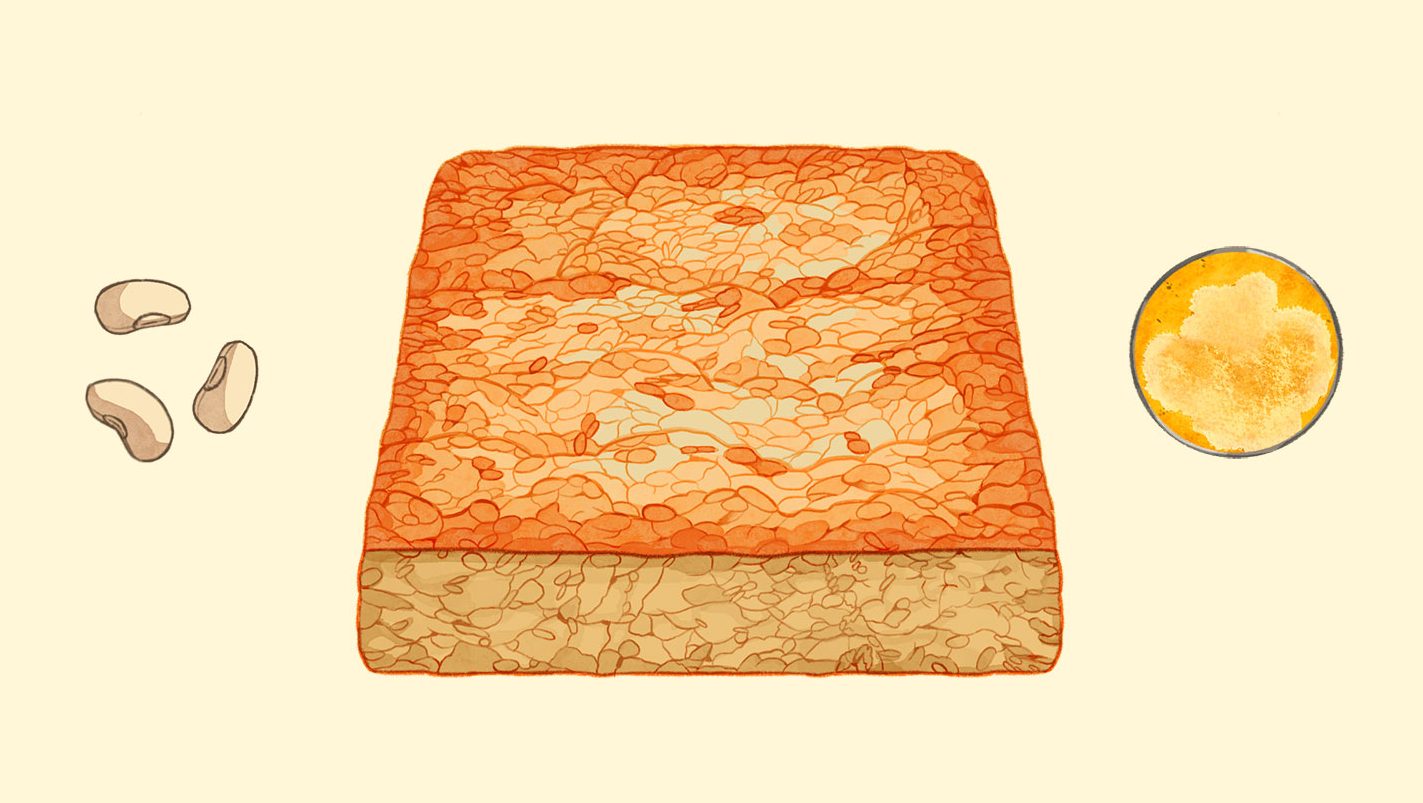

Making oncom is almost magical. It starts with a pile of soy pulp, which is wrapped in banana leaves and with the spores of a fungus called Neurospora intermedia. The batch is left to ferment in a warm, humid place for about a day and a half. As the mold digests the proteins and starch within the fibrous pulp, it also breaks down the cellulose, which remains in a dish beloved by many people across western Indonesia.

“It’s pretty amazing,” said the chef, bioengineer Vayu Hill-Maini. “In just 36 hours, this fungal growth is really transforming something else that’s pretty much inedible.”

He hopes others see it that way too. In a recently published article in Nature Microbiologythe Stanford University assistant professor made a compelling case that fungal fermentation of food waste and agricultural byproducts could be the next culinary frontier.

For Hill-Maini, it’s about more than making trendy dishes. It is about improving food sustainability and reducing hunger worldwide. The process he’s so excited about has been doing just that for centuries in parts of Indonesia, where oncom, a traditional staple food, is an affordable and nutritious alternative to animal protein.

Patrick Farrell / UC Berkeley

Stir fried; used as a stuffing, stuffing or base of sauce; and even served as a fried snack, oncom is traditionally made by combining some old oncom with something like soybean pulp and letting it ferment. This is much like making miso, and results in a protein similar to tempeh. Its appearance in Southeast Asian cuisine inspired Hill-Maini, who once worked as a chef, to investigate the spore-bearing organisms behind the dish and find out how the fungus that creates it could be embraced globally.

Fermentation has been around for thousands of years. It’s what makes beer and wine possible, and has long been used to whip up kitchen table staples like kimchi, sauerkraut and yogurt. It’s even behind kombucha and sourdough bread. But it turns out that this chemical process, in which bacteria, molds or yeasts break down sugar to create simpler compounds, could help alleviate the growing crisis of food waste. Hill-Maini thinks it could, in theory, do this by turning waste generated during the production of plant-based milk into cheap and highly nutritious dishes, helping a key source of greenhouse gas emissions generated by the world’s food system.

“We’ve known for many years that fungi are nature’s decomposers,” Hill-Maini said, noting that fungi used to reduce streams of food waste may be the “most efficient way to turn waste into human food.”

Hill-Maini’s paper is the result of three years of investigating just where N. intermedia can grow, and whether it can turn the layoffs and waste from industrial food processing into something people will want to eat. After analyzing everything from coffee grounds to orange peels — about 30 things in all — he and his team discovered that the fungal strain grew on almost everything they tried. They also found that it does not produce mycotoxins, the potentially deadly substances associated with some fungi.

And, perhaps most notably, it has led to the creation of foods that repurpose what might otherwise end up in the garbage without sacrificing taste in the interest of altruism. Just as importantly, he wanted the process to be widely accessible.

“This is industrial scale. These are not compost bins and home kitchens. These are massive industries that generate food waste products every day,” said Hill-Maini.

The research focused in particular on what is left behind during the production of plant-based dairy, produceand brew. Interestingly, Hill-Maini discovered that many of these inedible items can be transformed into something with appetizing colors, textures and flavors.

This can be a boon for the climate because evidence suggests every metric ton of wet waste reused through fermentation – in this case, turned into dinner instead of methane-spit out landfills — prevents the release of approximately 600 kilograms of CO2. Before long, Hill-Maini would like to see fungal fermentation incorporated into food manufacturing facilities and any emerging waste immediately transformed through mold.

But what really fascinates him is the climatic benefits of N. intermedia could provide. “What we think is that we can convert this waste into protein, and then that protein can reduce animal consumption,” Hill-Maini said. “We might have a massive impact.”

Getting enough American consumer interest in food made from waste will require a pitch that goes beyond the increasingly useless message “it’s better for the planet.” But that kind of branding may not be necessary. Rick von Hagn, who has been experimenting with N. intermedia at Blue Hill at Stone Barns for the past few years, says the taste and texture of this ancient way of cooking may do the trick on its own. The farm-to-table restaurant in Tarrytown, New York, has begun serving mushroom-fermented foods in a handful of dishes.

His journey on the trail began in 2022, when he and colleague Andrew Luzmore began working with Hill-Maini to identify various kitchen waste streams that could be good candidates for fermentation. They would send something to the bioengineer, who would send back a fermented food, the first of which started out as “the presscake that’s left over when you make flaxseed oil,” Luzmore said. “I remember taking out what looked like a burger patty and placing it in a hot pan. As it cooked, it started to look like a well-seared steak.”

They have since discovered that combining the fungus with a wide variety of ingredients provides a textural and flavor additive that can transform even the most difficult alt-protein dishes into a culinary star. The two chefs used N. intermedia to improve the texture of sausage made with a mixture of meat and grain or vegetables, and brought rock-hard bread “back to life” by fermenting it with the fungus and keeping it out of local landfills. The rejuvenated bread “has the texture of French toast and the flavor of grilled cheese.” As it ferments, N. intermedia takes on an “earthy, floral quality,” noted von Hagn, and cooking it provides “a cheesy, deeply savory, mushroom-like flavor and aroma.”

Using the fungus in dishes was such a hit with customers that the team at Blue Hill built its own microbiology lab to evaluate the potential to ferment various things and develop recipes with them. It is, as Luzmore described it, “a key to a whole new set of possibilities that have remained largely unexplored outside of its traditional use in Indonesia.”

Matthew Kammerer, executive chef at The Harbor House Inn in Elk, California, loves that idea. “Any cooking that is done with by-products or turned into something unique to limit food waste is something I will definitely always support,” says Kammerer, who was not involved in the research project.

For the last seven years, Kammerer has been working with koji mold, or Aspergillus oryzaewhat is widely used in Japanese cuisine to ferment soybeans and make things like soy sauce and miso. In the past decade, “koji has kind of been the star of the show, but it seems like a very similar process and technique,” Kammerer said. He is interested in learning more about N. intermedia’s gastronomic potential, which he calls “much less mainstream”.

All told, it’s not just fine-dining restaurants in the US that can be found embracing the culinary novelty of this Indonesian technique. Hill-Maini is working closely with San Sebastián, a Michelin-starred restaurant in Spain, with the aim of developing alcoholic beverages using N. intermedia. Chefs at Alchemist, a Michelin-starred restaurant in Denmark, have created a dessert in which the fungal enzymes enhance the sweetness and flavor of a sugar-free rice custard.

Vayu Hill-Maini / UC Berkeley

The biggest obstacle to the adoption of this strain of fungus is the lack of places to buy the spores needed to grow it in the US. In Java, the Indonesian birthplace of oncom, oncom leftovers are used much like seeds to make a new batch of the alternative protein — a process similar to using sourdough starter to make bread. In California, Hill-Maini’s team used a laboratory sample of N. intermedia to conduct its research. That limited availability is one of the reasons Luzmore and von Hagn went all out in a microbiology lab, while Hill-Maini is building a kitchen next to his Stanford lab.

Of course, the steeper hurdle is getting people to eat something that many consider junk.

“There are a few things working against us. We talk about waste, we talk about form. If you say ‘mold-fermented waste,’ I think people would be really turned off and disgusted,” he said. It’s true that having chefs who eat well can help reverse people’s aversion to trend.

The irony is fermented food products, such as sourdough, and those full of fungi, such as blue cheese, have long dominated the food scene in the US Kombucha – the beloved musty, fermented drink that hit astronomical popularity recent years, but was first brewed millennia ago – is one such success story. Hill-Maini hopes to see a similar kind of rocket-like trajectory for N. intermedia.

Embracing a fungus that fights food waste on kitchen tables and restaurant plates around the world is not the future of food, Hill-Maini said, but the present. “Look, this is happening in Indonesia. It happens in various ways in the US,” he said. “It’s just a new way of looking at it, at planetary health.”

He and his team are not reinventing the wheel, but rolling it into a new part of the world as a force for planetary good. One discarded pile of oatmeal or moldy bread, at a time.