As President-elect Donald Trump gears up for his second term in January, things may look bleak for those who want to see the United States tackle climate change. Trump has pledged to expand fossil fuel production and undo much of President Joe Biden’s climate agenda, saying he will roll back environmental regulations, cut federal support for clean energyand withdraw from the Paris climate agreement — again.

But a certain brand of Republicans still hopes to push the incoming administration to tackle climate change, the “America First” way. In a statement Congratulations to Trump on his victory last week the American Conservation Coalition, a Washington, DC-based group trying to build a conservative environmental movement, laid out the case for a cleaner future by emphasizing the economy, innovation and competition with China. “In the 20th century, America put a man on the moon and the Internet in the palm of our hands,” the group’s statement reads. “Now we will build a new era of American industry and win the clean energy arms race.”

The rules read as if they came from a parallel universe where Republicans, rather than Democrats, prioritized climate change. In fact, the belief that humans are driving global warming is one of the issues the partisan gap has widened the most in the past two decadesand Republican politicians regularly to attack climate solutions such as wind and solar power.

But in recent years, behind the scenes, congressional Republicans have been talking to each other about how their party might be able to address rising carbon emissions. Even red states like Arkansas and Utah have bipartisan policies that help the climate quietly passedalthough they are often less ambitious than Democrats propose and are rarely promoted as “climate action.”

“I don’t think progress will stop,” said Renae Marshall, who researches bipartisan cooperation on climate change at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “I think it will only be more difficult.”

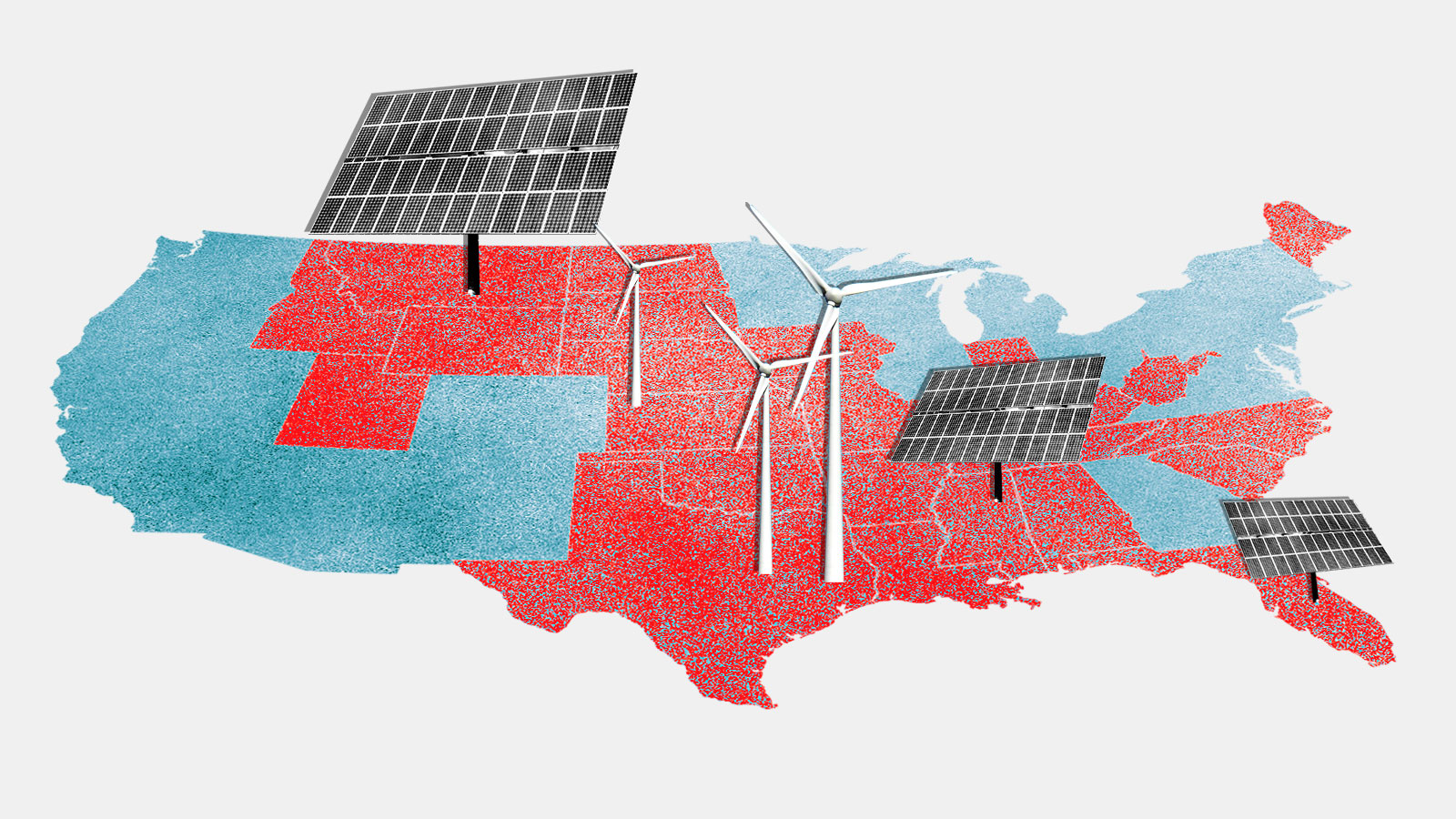

Republicans are not a monolith, as 54 percent of them say they support the U.S. participating in international efforts to reduce the effects of climate change, and 60 and 70 percent, respectively, say they want more wind and solar farms. Younger Republicans in particular are also less supportive of fossil fuel expansion, Pew Research surveys show.

“Climate change is less polarizing than we think,” said Matthew Burgess, an environmental economist at the University of Wyoming. “Let’s notice it and say it out loud, and work with it.”

For an example of what is politically possible, take the Energy Act of 2020, signed by Trump during the final year of his presidency. The law, which passed a Democratic House and a Republican Senate, included investments in renewable energy, energy efficiency, carbon capture and nuclear energy. It also phased out the production of hydrofluorocarbons, so-called super-pollutants, which are thousands of times more powerful than carbon dioxide at warming the atmosphere.

Now with both the Senate and the House of Representatives in their control, Republicans see an opportunity reform the permitting process for new energy projects. The idea is to make it faster and easier to approve both fossil fuel projects as well as clean energy projects. The United States’ recent boom in oil and gas development have already put the world’s climate goals at risk, so support for relaxing permit rules can backfirebut the American Conservation Coalition sees it as essential.

“During a second Trump presidency, we can expect robust reform efforts that will make it possible to build in America again, coupled with an energy dominance agenda that will put American energy first on the world stage and reduce global emissions,” Danielle B Franz, the coalition’s chief executive, in a statement to Grist. “We advise those in the climate community to approach the second administration with good faith about skepticism.”

Even if progress stalls at the federal level, precedent suggests that states under Republican guidance can adopt energy policies that reduce emissions. During the same era Trump was last in office, from 2015 to 2020, Arkansas, South Carolina and Utah introduced legislation to pave the way for the expansion of solar and wind power. Of the approximately 400 state-level bills to reduce carbon emissions from that period, 28 percent of them passed through Republican-controlled legislaturesaccording to Marshall and Burgess’s research.

Their analysis showed that these laws, which carried bipartisan support, had some important things in common. They’ve tended to expand energy choices rather than limit them—think removing red tape for solar projects, as opposed to banning new gas stoves. The bills that received bipartisan support were also more likely to emphasize the concept of “economic justice,” meaning that they aimed to help people with lower incomes, rather than using language associated with race or gender related. “The best way to depolarize it is to get it as far away from the culture wars as you can,” Burgess said.

The rare Republican politicians who speak openly about climate change often distance themselves from their Democratic counterparts. “I think anyone who’s had a chance to hear me talk about climate understands that I’m doing it from a very conservative perspective, so much so that the left would say, ‘You’re not serious about it,'” says Representative John Curtis of Utah, who was just elected to the Senate, in a conversation with reporters last month.

Curtis has the Conservative Climate Caucus in 2021 to get House Republicans talking to each other about climate change and thinking through what a conservative-friendly approach to the problem might look like, with the goal of offering alternatives to “radical progressive climate proposals that would harm our economy, American workers , will hurt, and national security,” according to the group’s website. The caucus now has 85 members.

“It kind of serves as this, like glue, this social capital glue, that helps them talk together about climate when they might not have otherwise,” said Marshall, who watches the caucus. Liberals sometimes question the utility of talking to Republicans about climate change, she said, but she believes bipartisanship is necessary for long-term progress.

Even with Trump’s expected onslaught on regulations, Burgess expect US greenhouse gas emissions to continue to decline in the coming years, as states and businesses do much to reduce carbon emissions. He also thinks that the climate policies passed by Congress during the Biden era can be protected: they either passed with Republican support or, in the case of the Inflation Reduction Act, which poured hundreds of billions of dollars into green technology invested, favoring mostly Republican districts. Biden’s climate policies, Burgess said, “are almost perfectly designed to be bipartisan” — so it’s possible they could survive a second Trump administration mostly intact, despite all the trouble.