Like wildfires chewing through parched forests, hurricane after hurricane this summer fed on extra-warm seawater and crashed before slamming into communities along the Gulf Coast, causing hundreds of billions of dollars in damage and killing more than 300 people. The warmer the ocean, the more powerful the hurricane fuel, and the more energy a storm can consume and turn into wind.

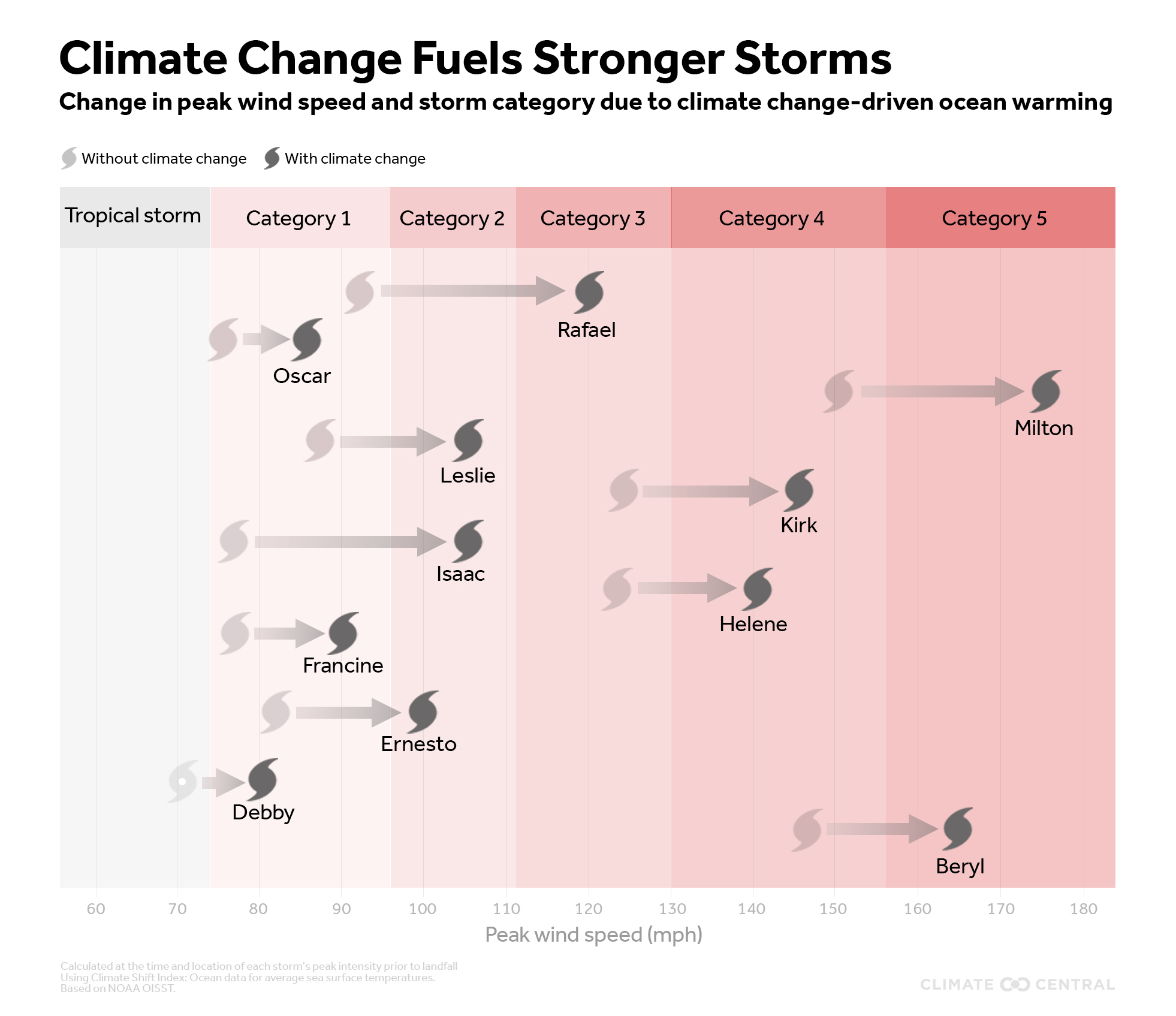

Man-made climate change has made all of this season’s 11 hurricanes — from Beryl to Rafael — much worse, according to an analysis released Wednesday from the nonprofit science group Climate Central. Scientists can already say that 2024 is the hottest year on record. By helping to drive record-breaking surface ocean temperatures, planetary warming has increased hurricanes’ maximum sustained wind speeds by between 9 and 28 miles per hour.

It has seven of this year’s storms in a higher category on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scaleincluding the two Category 5 storms, Beryl and Milton. “Our analysis shows that we would not have had any Category 5 storms without human-caused climate change,” Daniel Gilford, climate scientist at Climate Central, said on a press call. “There really is this impact on the intensity of the storms that we experience on a daily basis in the real world.”

In a companion study also released Wednesday, Climate Central found that climate change accelerated hurricane wind speeds by an average of 18 mph between 2019 and 2023. More than 80 percent of the hurricanes in that period were made significantly more intense by global warming, the study found.

This makes hurricanes more dangerous than ever. An 18 mph boost in wind speed may not sound like much, but it can mean the difference between a Category 4 and a Category 5, which packs sustained winds of 157 mph or higher. Hurricanes have gotten so much stronger that scientists are considering changing the scale. “The hurricane scale is limited to category 5, but we might have to think: Should that still be the case?” Friederike Otto, a climatologist who co-founded the research group World Weather Attribution, said on the press call. “Or should we talk about Category 6 hurricanes at some point? Just so that people are aware that something is going to hit them that is different from anything they have experienced before.”

Hurricanes need a few ingredients to turn up. One is fuel: As warm seawater evaporates, energy is transferred from the surface to the atmosphere. Another is humidity, as dry air will help break up a storm system. And a hurricane also cannot form if there is too much wind shear, which is a change in wind speed and direction with height. So even if a hurricane has high ocean temperatures to nurture, it’s not necessarily a guarantee that it will turn into a monster if wind shear is excessive and humidity is minimal.

But during this year’s hurricane season – which runs until the end of November – those water temperatures were so extreme that the stage was set for disaster. As the storms traveled through the open Atlantic, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, they exploited surface temperatures made up to 800 times more likely by human-caused planetary warming, according to the Climate Central analysis. Four of the most destructive hurricanes – Beryl, Debby, Helene and Milton – saw wind speeds increase by an average of 17 mph, thanks to climate change. In early November, Hurricane Rafael managed to jump from category 1 to category 3.

Climate Central’s companion study, published in the journal Environmental Research: Climate, looked at the five previous years and found that climate change pushed three hurricanes — Lorenzo in 2019, Ian in 2022 and Lee in 2023 — to Category 5 status. That’s not to say that climate change caused any of these hurricanes, just that the added warming from greenhouse gas emissions made the storms worse by raising ocean temperatures. Scientists also find that hurricanes may dump more rain as the planet warms. In October, for example, World Weather Attribution found that Helene’s rainfall at the end of September 10 percent heaviermaking flooding worse as the storm moved inland.

All that supercharging could have helped hurricanes undergo rapid intensification, defined as an increase in wind speed of at least 35 mph within 24 hours. Last month, Hurricane Milton’s winds soared 90 mph in a dayone of the fastest rates of intensification scientists have ever seen in the Atlantic basin. In September, Hurricane Helene also intensify quickly.

This kind of intensification makes hurricanes particularly dangerous, as people living on a stretch of coastline may be preparing for a much weaker storm than actually makes landfall. “It throws off your preparations,” said Karthik Balaguru, a climate scientist who studies hurricanes at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, who was not involved in the new research. “This means you have less time to evacuate.”

Researchers also find that wind shear may decrease in coastal areas due to changes in atmospheric patterns, removing the mechanism that keeps hurricanes in check. And relative humidity rising. As a result, scientists have found a big increase in the number of rapid intensification events near the coast in recent years.

The warmer the planet gets in general, and the warmer the Atlantic gets specifically, the more monster hurricanes will grow. “We know that the speed limit at which a hurricane can rotate is increasing,” Gilford said, “and real-world hurricane intensities are responding.”