The spotlight

At a library in Dover, New Hampshire, earlier this year, the shelves of books and CDs typically available for lending were accompanied by something else — racks of clothing. Every Sunday and Monday from December to mid-January, community members could visit a lecture hall in the Dover Public Library to participate in the piloting of a new type of lending project: a clothing library. Visitors could check out up to five garments at a time for two weeks. The collection focused on “occasion wear,” the type of thing people might buy for the purpose of wearing once: a holiday party dress, a wedding outfit, a ski trip ensemble.

But more than displacing those types of purchases, and the resulting waste, the real idea behind the project was to facilitate a shift in behavior, said Stella Martinez McShera, the clothing library’s creator. “How can we bridge the gap between people buying, whether new or second-hand, and lending?”

McShera with the clothing library setup. Courtesy of Stella Martinez McShera

I met McShera while reporting on another newsletter story the world’s first degrowth master’s program, run by a university in Barcelona. She is a recent graduate of the online master’s degree, and the clothing library was her thesis project. In that story we explored what happens when the philosophical ideas of a new economic system meet the realities of the one we have. McShera’s project is one example of what this looks like in practice.

![]()

McShera began her career in fashion. In 2000, she launched the first fashion incubator in the US. But as much as she loved the essence of fashion, she knew that the industry was guilty of horrific human rights abuses, pollution and waste. She had long been interested in circular fashion, but she began to feel that even a circular approach was not enough to get to the root of all the ills associated with fast fashion. When she discovered degrowth and the master’s program, it became a testing ground for her ideas about replacing fast fashion and extraction with borrowing and being inventive with what already exists.

McShera began building her clothing library pilot by collecting excess clothing from local thrift and vintage stores. It is estimated that second-hand shops only approx 20 percent of the donated clothes they receive. Even vintage boutiques and curated consignment shops will eventually get rid of some garments they couldn’t sell in a set amount of time. “They have to drive in well,” she said. “So even if it’s something really cute, maybe they overpriced it at the thrift store, or maybe it just didn’t sell in two weeks because it’s a sweater and it’s unseasonably warm.”

From local thrift stores alone, McShera quickly amassed more than 5,000 items of clothing — even more than she could handle, she said. She donated her own surplus to a housing shelter, growing the library collection to about 1,500 items.

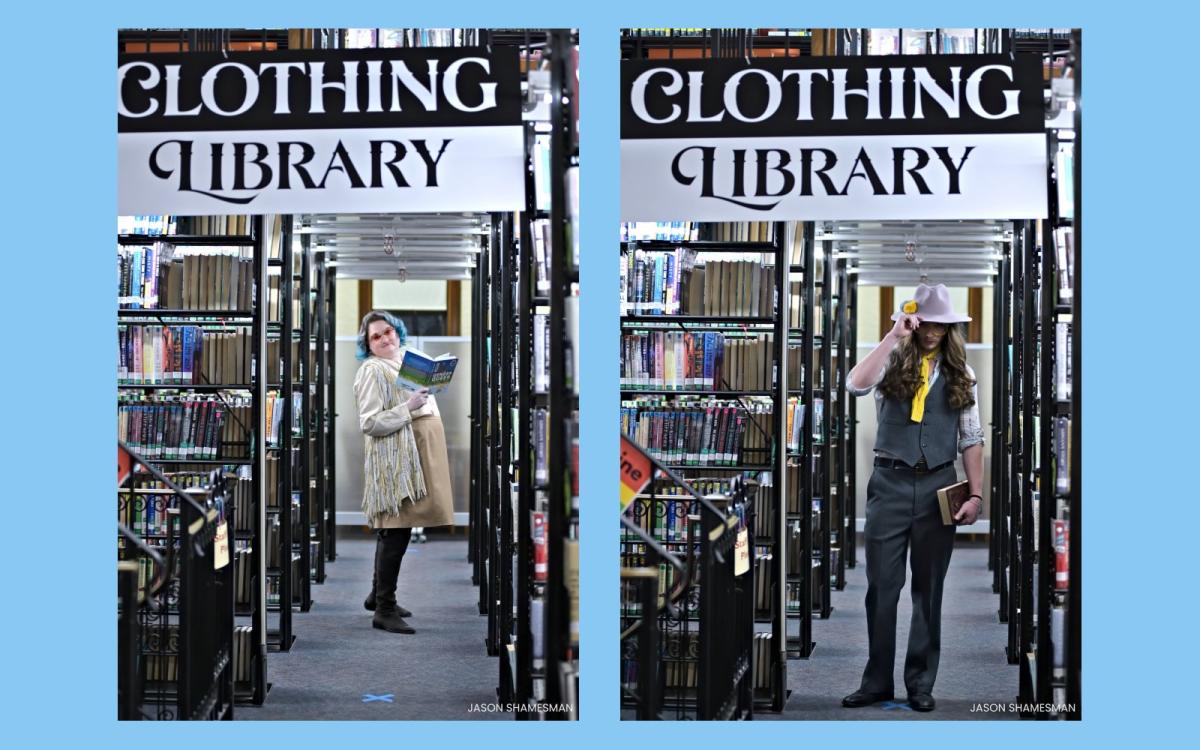

McShera kicked off the launch with a fashion show in the pile. Professionally carved librarians modeled items from the collection for photographers and a crowd of over 160 attendees. “It was so much fun,” said Denise LaFrance, the Dover Library’s director. The fashion show was the largest indoor event at the library in her 25-year tenure. “I mean, seriously, people are still talking about it.”

Models walk the runway during the fashion show at the Dover Public Library. Jason Shamesman

During the launch, McShera also hosted an eco-fashion panel and three workshops on mending and styling, intended to help people rethink their relationship with their wardrobes. “Because it’s free, people have been more willing to experiment with their style,” McShera said. There was no guilt or shame attached to returning something, because returning was an understandable part of the process.

Among other things, LaFrance borrowed a pair of gray silk pants that she remembered loving, even though they weren’t the type of thing she usually shops for. When she checked them out, they still had their original price tags attached. They sold for about $400. “I would never buy $400 pants,” she said. “But they were fantastic.”

Over 12 days of being open, McShera said, the library has seen more than a hundred people come through, and 65 have borrowed something. And of the more than 100 items of clothing checked out during the library’s pilot, all came back clean and in good condition.

“It’s the community of clothes,” McShera said. “It’s free access versus ownership.”

![]()

With the pilot project completed and McShera’s thesis completed, she is now looking at the next steps to make clothing libraries a reality in her community and beyond. She presented the concept at the 10th International Outgrowth Conference in Spain last week, and plans to publish a manual that will empower community members around the world to start their own projects, in collaboration with their local libraries. One day, she’d like to see a network of clothing libraries—sharing resources and knowledge, advocating for policy change, and possibly even swapping clothes to keep their collections fresh.

Although she feels there is more testing to be done, a few more local libraries in her area have already expressed interest in hosting a pilot, she noted.

“The hardest thing about this was space and time,” LaFrance said. The library is in an old building, she said, “and we’re kind of bursting at the seams.” She suspects that most libraries will be similarly squeezed to carve out space for a small store’s clothing racks. One thing she suggested to McShera was a setup more like a tour bus.

But McShera’s ultimate vision is to integrate clothing into the normal functioning of a library. “The reason why I wanted the model to be in partnership with the public libraries is because the behavior is normal. People already know, I go in and I borrow,” she said. She added that libraries tend to be centrally located in cities and neighborhoods, highly visible and easily accessible on foot or by transit. And many libraries — including Dover’s — are already branching out from books, lending out things like tools, games and music.

“It just seems like a logical next step,” she said.

Rather than a pop-up in an event space, she envisions a future where clothing racks can find a permanent home in the library. There may even be regular staff members with fashion expertise who can curate the collections. “Just like if someone needs help using the photocopier or help researching something, you ask the librarian for help,” McShera said. “So if you wanted help with styling, you could say, ‘Hey, is there a clothing librarian on shift today?'”

– Claire Elise Thompson

More exposure

A parting shot

It has become increasingly common for public libraries and other community-serving organizations to “libraries of things” — collections of functional things that people might want to borrow for a short time, such as toys, gadgets, musical instruments, and more. Here is a photo of such a presentation in the corner of a library in Frankfurt, Germany.