President Biden’s administration wants to create that largest non-contiguous marine protected area in the world, but a new paper says the effort fails to take into account the rights and perspectives of the indigenous peoples most affected by the change.

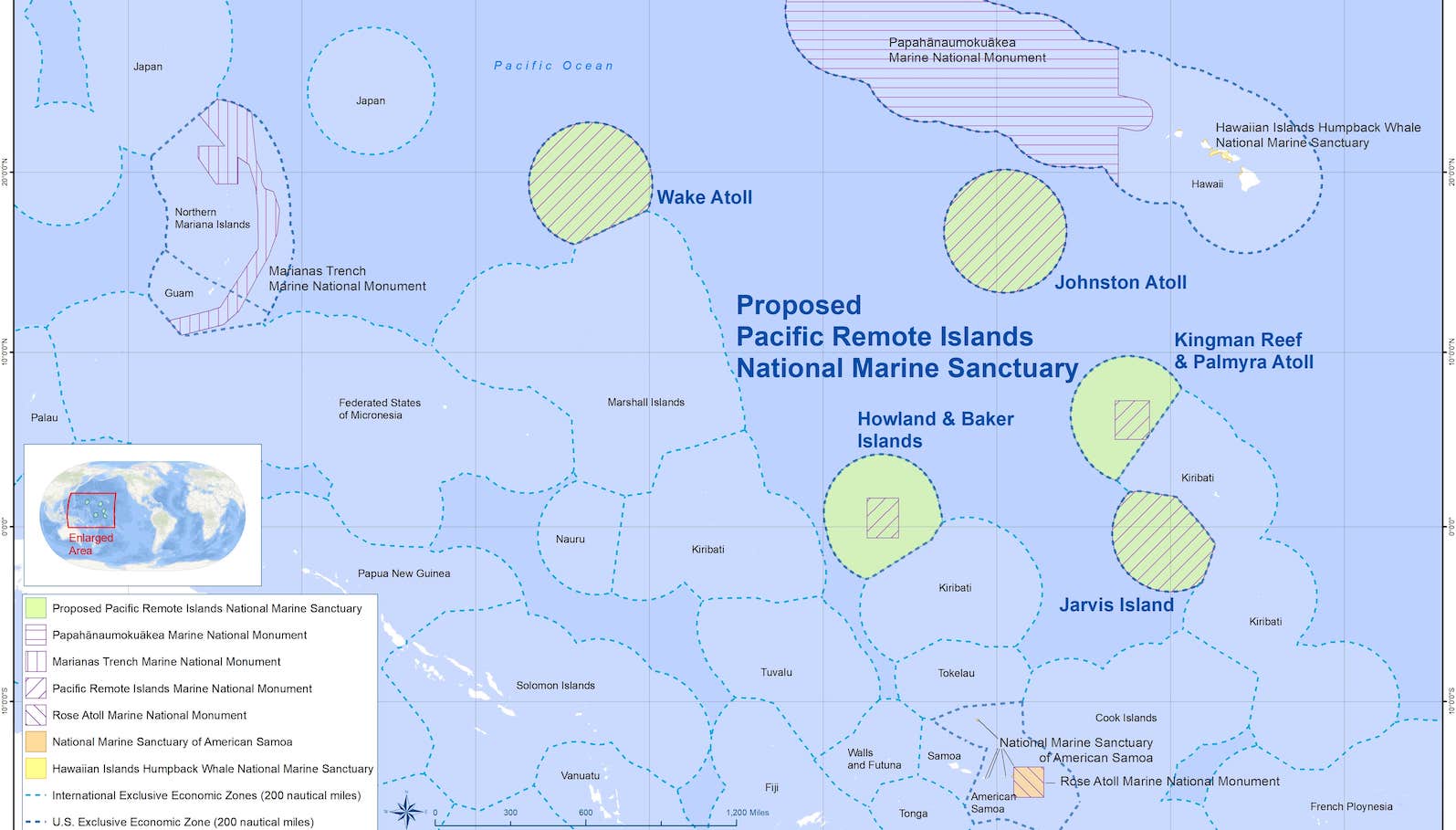

The Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument was established in 2009 and currently conserves nearly half a million square miles of ocean around seven islands in the central and western Pacific. The Biden administration is seeking to strengthen environmental protections by capping and expanding the protected area to 770,000 square miles and designating it a national marine sanctuary. The monument already prohibits commercial resource extraction such as deep-sea mining, but the proposed sanctuary would both expand the protected waters and give the entire area an additional layer of federal protection.

The expansion would also make a dent in the Biden administration’s goal of conserving 30 percent of the nation’s land and water by 2030.

Courtesy of NOAA

According to Angelo Villagomez and Steven Manaʻoakamai Johnson, authors of the peer-reviewed article in Environmental justicehas the Biden administration privileged native Hawaiian perspectives (supporting the expansion, which does not extend to the archipelago) over those of other indigenous Pacific Islanders, namely Micronesians and Samoans, who have less political power in the US system and have expressed . more concern about the proposal.

“Anti-Micronesian bias and colonialism undermine efforts to protect and manage waters around US overseas territories in the Pacific Islands,” wrote the authors. “The proposal is problematic because it failed to meaningfully include the indigenous people who live closest to the region and who have the strongest historical and cultural ties to the islands – the Micronesians and Samoans.”

Villagomez, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress who is Chamorro and grew up in the Mariana Islands, has been advocating for marine protected areas for more than 15 years. When he started this work, back in 2007, Villagomez tried to organize support in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands for the Marianas Trench National Marine Monument, which preserves nearly 100,000 square miles of water in the Marianas Archipelago. Although the proposal faced backlash from local residents who worried the move would infringe on indigenous sovereignty, Villagomez thought the monument would not only help the planet but also bring federal jobs to the area. He was in the room celebrating when then-President George W. Bush signed the monument in 2009, which was hailed as a major environmental achievement.

For years afterward, Villagomez watched as government work for the monument was concentrated in Hawaii. The office was located in Honolulu, thousands of miles from the monument. Research vessels were equipped and crewed from Honolulu with people who came from Hawaiʻi and other states. It was disappointing to see that these benefits did not help the people of the Northern Marianas, who have a much more fragile economy. After all, he saw how the 2006 Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Monument in the northern Hawaiian Islands gave Hawaiʻi a boost in prestige and research funding.

“We worked under the assumption that [the Marianas monument] would work like [the one in] Hawaiʻi,” Villagomez said. “But the difference is that Hawaii has two senators, and they have representation in the House of Representatives, and they can vote for president. And we just don’t have the political power to bring the dollars to our islands like Hawaii.”

Only recently has an office for the Marianas Trench monument been opened in the Commonwealth. And just last month — 15 years after monument designation — the Department of the Interior released a proposed management plan for the Marianas Trench Monument. Villagomez thinks the delays reflect a broader disregard for the areas he sees unfolding again in the Pacific remote islands designation effort.

“The process of colonization not only plays out with the colonizer and the colonized, but it also plays out in relationships between colonized people,” said Steven Manaʻoakamai Johnson, Villagomez’s co-author who is an assistant professor of natural resources and the environment is. at Cornell University. “In this case, what we’re trying to highlight is that the Hawaiian perspective and the Hawaiian voice is privileged, over that of the Micronesian and Samoan voice.”

For example, the official community group advising government agencies on the monument includes a designated Native Hawaiian representative, but not an equivalent role for other Native peoples, Villagomez and Johnson wrote.

Similarly, in documents describing the cultural significance of the islands, marine sanctuary advocates often describe the sacrifices of Native Hawaiians who lived on Howland, Baker, and Jarvis Islands during World War II, and ignore the comparable sacrifices of native Chamorros killed on Wake. Island and the fact that most of the islands within the monument’s coverage are part of the Micronesian region, Villagomez and Johnson wrote.

Sarah Marquis at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said the agency plans to release a draft plan for the sanctuary designation later this year and will then accept further public input on the proposal. “We cannot comment on specific papers or articles at this stage of designation,” she said.

Naiʻa Lewis, a member of the Pacific Remote Islands Coalition who advocated for the sanctuary designation, said the group has long advocated for inclusivity through avenues such as co-management and renaming.

“It’s really important when we critique frameworks that we feel don’t support our communities and our perspectives that we also highlight people, organizations and communities that are working in that space to make those changes,” Lewis said.

Villagomez said a major impetus for the paper’s release was the importance of Pacific Ocean areas to U.S. ocean conservation goals: 29 percent of the nation’s ocean territory surrounds Guam, American Samoa and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and 99 percent of the country’s marine protected areas is in the Pacific region. Villagomez said he would like to see the areas benefit from those protected areas, such as jobs and funding, but said they sometimes can’t even get their own people on the boats who explores those waters.

In American Samoa, political leaders have long opposed monuments restricting commercial fishing. Although conservation supporters points to a recent study showing that relatively few ships calling at Pago Pago, its primary port, are actually fishing in the proposed Pacific Remote Islands Sanctuary, fears of economic damage persist. These concerns are particularly relevant when the islands’ struggling economies continue to experience large out-migration and make it difficult for areas to provide essential medical care for their residents.

In the Northern Mariana Islands, commercial fishing is not a major industry, but critics of the marine monuments have argued that closing large areas of the sea to potential economic activity violates their right to indigenous economic self-determination and is particularly egregious when the same areas remain open for US military undersea sonar training and explosives testing.

“Our already disadvantaged and marginalized communities bear a disproportionate burden to meet national conservation goals,” the governors of American Samoa, Northern Mariana Islands and Guam wrote in a joint letter to Biden last year.

Villagomez and Johnson both support ocean conservation, but argue that any marine sanctuary designation should include dedicated funding for the affected areas and peoples, and call on NOAA to create such a fund.

“These are the areas that live with the decisions,” Villagomez said. “But it’s people in Washington DC and Honolulu who are forcing the territories to bear these burdens for the rest of the country.”