Among those concerned about the climate, it has become something of a self-evident truth that as people experience more severe and more frequent extreme weather and grapple with global warming’s impact on their daily lives, they will understand the problem on a visceral level . Consequently, they will be eager for action. In other words, many climate activists believe that even if advocates and academics can’t sway the hard-line opinions of the naysayers, extreme weather can wake anyone up.

The data disagree.

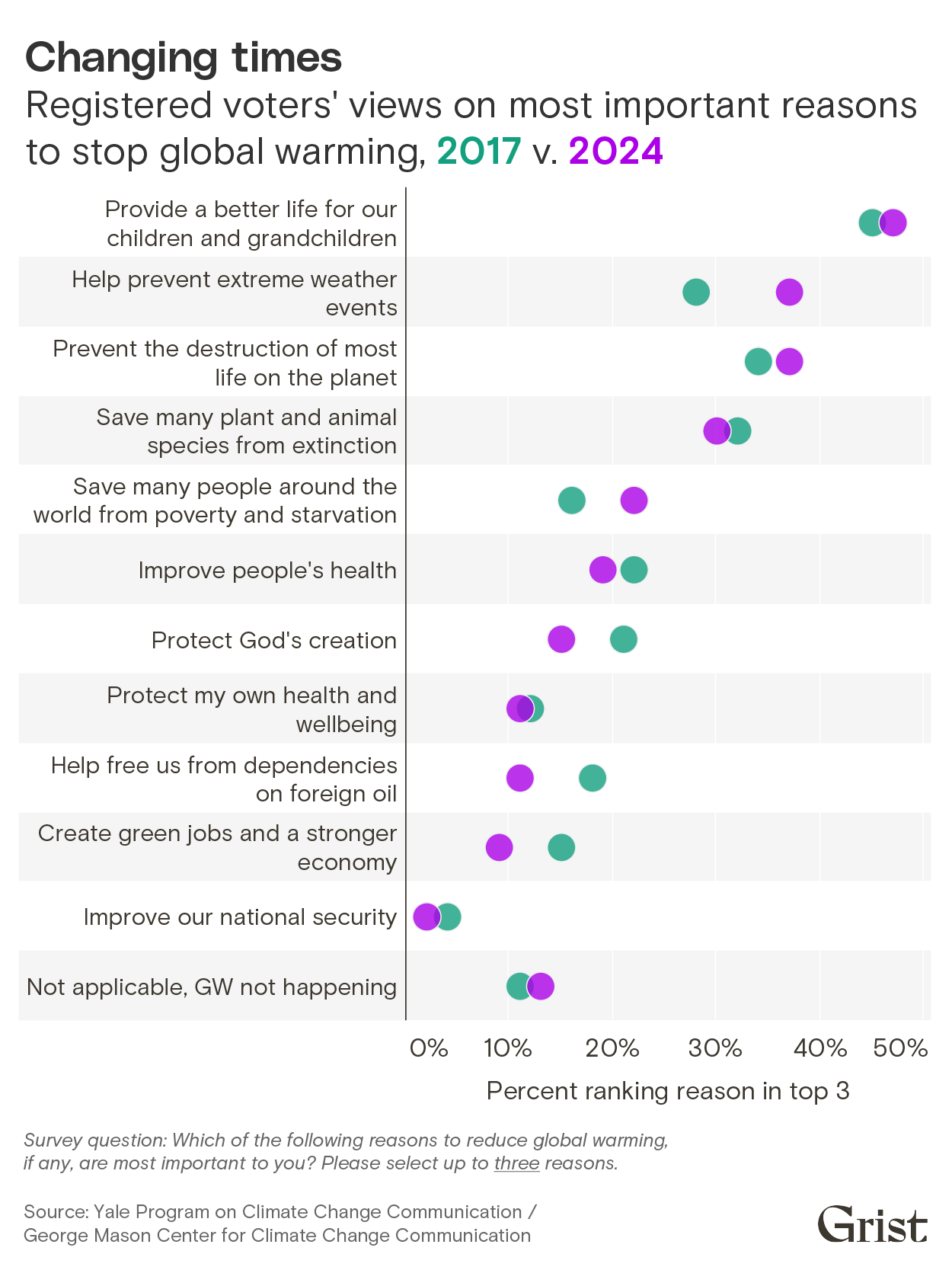

Over the past seven years, as the effects of climate change have begun to shroud the world in smoke and storm, natural disasters have actually jumped ahead of voters when considering the most important reasons to take climate action. However, these concerns are not shared equally across the political spectrum.

Preventing extreme weather was among the top three reasons for addressing the crisis among 37 percent of voters surveyed this year, according to an analysis by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. That’s up from 28 percent seven years ago. For Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale program, this shift reflects the fact that, while many Americans view climate change with a certain psychological distance, the increasingly shared experience of smoke-filled air, life-threatening heat and earth-shattering droughts means “Climate change is not more distant in time and space,” Leiserowitz said. “It’s right here, now.”

Mainstream media outlets are making this increasingly clear to their audiences, thanks in large part to the burgeoning field of attribution science that allows researchers to describe the links between global warming and a given weather system in real time.

The shift that Leiserowitz and his colleagues detected was largely driven by moderate and right-leaning Democrats. In 2017, less than one-third of those voters included preventing extreme weather among their top three reasons for wanting action, but by this year, half of moderate and conservative Democrats ranked it that high. However, the opinions of moderate and left-leaning Republicans remained mostly unchanged, with just under 30 percent of voters citing extreme weather as a top three reason to reduce global warming. Perhaps surprisingly, extreme weather has even increased in relevance among conservative Republicans, with 21 percent citing it as a leading reason compared to just 16 percent in 2017.

But even as extreme weather became more salient among the most conservative voters, many more of them chose the survey option “global warming is not happening.” In 2024, a full 37 percent of conservative Republicans denied the reality of climate change, up from 27 percent just seven years earlier.

“People’s beliefs about climate change are primarily driven by political factors,” said Peter Howe, an environmental social scientist at Utah State University who has worked with Leiserowitz in the past but was not involved in this analysis. The political and social circles a person occupies and the beliefs they hold not only mediate a person’s overall opinions about climate change, Howe pointed out, but influence how that person experiences extreme weather.

When Howe collected and reviewed studies showing the connections between extreme weather and personal opinions on climate change, he found that while those already concerned about the crisis often had their worries exacerbated by a natural disaster, those who were dismissive before the event often remained so, ignoring any potential link to global warming.

When Constant Tra, an environmental economist at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, and his colleagues published a similar study in May he found that disasters do not drive people to worry and alarm as he expected. At best, “it kind of bumps people up,” he said, but rarely does anyone move from an entrenched position of categorical denial, especially when those around them aren’t concerned.

This dynamic mirrors a groundbreaking experiment conducted in 1968 in which a college student was placed in a room with two actors. As smoke dripped into the room, if the actors pretended everything was fine, the subjects rarely reacted with alarm or reported the smoke. In fact, they often assumed it was not dangerous. In the climatic repetition of this “smoky room experiment” currently taking place in America, climate deniers play the role of the actors and try to convince everyone around them that everything is right. Over time, those views spread and positions hardened.

But the smoky room experiment and Leiserowitz’s own research make something clear: Worry can also be contagious.

However, shouting from the bell towers is not enough on its own, Leiserowitz added. “It’s really important that people have an accurate understanding of the risks,” he said, without exaggerating or ignoring the fact that every little bit matters. That clear accounting of the risks must also be accompanied by an exploration of the solutions that exist, that we can implement with ease and efficiency, and that can make a meaningful impact today.