In the final days before the presidential election, about 2,000 volunteers from across the country spend hours calling voters in 19 states. Their goal? Get people who care about climate change to the polls, especially those who didn’t turn out in the last presidential election.

You might expect this volunteer force, raised by the nonprofit Environmental Voter Project, to talk about a particular candidate. After all, Vice President Kamala Harris, a Democrat who cast the deciding vote for the largest climate bill in congressional history, contrast sharply with former President Donald Trump, a Republican who rolled back dozens of environmental protections and pulled the United States out of the Paris climate accord. Although it is true that most voters who prioritize climate change choose Democratic ticketsphone bankers for the Environmental Voter Project keep their message nonpartisan. In fact, their script doesn’t even mention climate change.

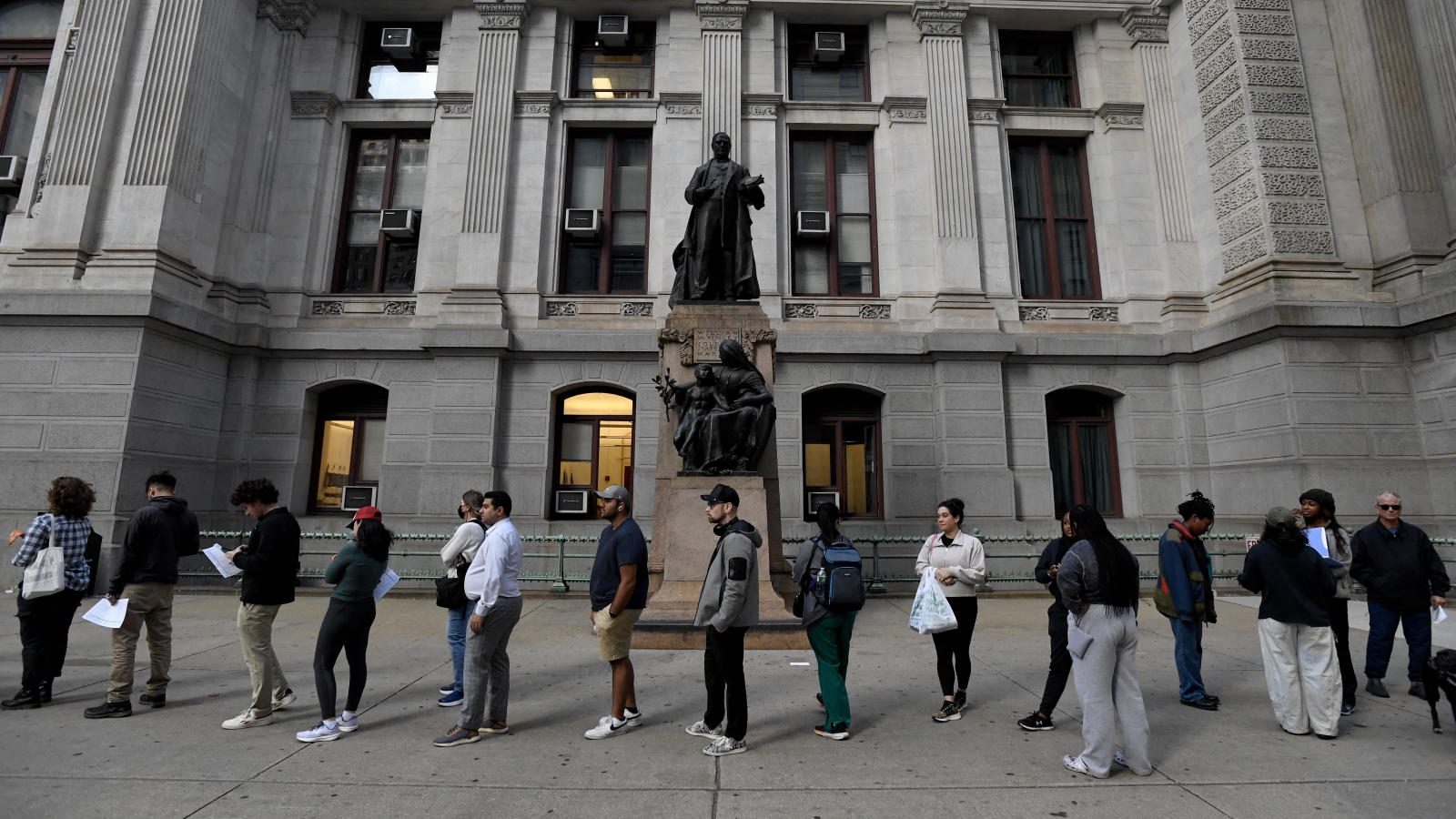

In an election expected to be won by a razor-thin margin, the estimated 8 million registered voters who care about the environment but didn’t vote in 2020 can swing entire states, especially states where the race is expected to be tight. The organization found 245,000 registered voters in Pennsylvania who care about climate change but rarely challenge it at the polls.

“Climate voters and first-time climate voters can absolutely make a difference this fall,” said Nathaniel Stinnett, founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project.

Research suggests that those climate voters who turned up in 2020 had a significant influence on the election. Climate change was the most important factor driving voters under 45 who previously voted third-party, or not at all, to cast their ballots for President Joe Biden in 2020, according to a Navigator Research Poll. Another analysis of the University of Colorado, Boulderfound that, hypothetically, Biden would have lost 3 percent of the popular vote if climate change did not play a role in voters’ preferences – enough to tip the election.

Matthew Hatcher/AFP via Getty

Stinnett believes the climate vote could be critical to this year’s presidential election in Pennsylvania, Georgia and North Carolina, the three swing states that have the largest share of voters who care about the climate but are unlikely to vote, according to the Environmental Voter Project’s modelling. Since 2017, the group reports that it has helped turn more than 350,000 previously inactive voters in Pennsylvania into super-consistent voters — in a state that Biden won by just 80,555 votes in 2020. In contrast, it does not reach out to voters in Michigan. and Wisconsin, because there aren’t that many non-voting environmentalists in those swing states.

Stinnett said that of the 4.8 million “potential first-time climate voters” volunteers are targeting in 19 states, nearly 350,000 of them cast their ballots early, which Stinnett sees as a promising sign. That includes 45,000 first-time climate voters in Georgia and more than 33,000 in North Carolina.

Anyone who lists climate change as their top priority is considered a climate voter. But some segments of Americans are more likely to be in this group than others: Democrats, women, young people, Black people, and those of Asian and Pacific Islander heritage. “If you’re more likely to feel the impact of toxic air and toxic water and extreme weather directly, well, you’re likely to care more about the climate crisis and environmental issues,” Stinnett said.

Of course, climate voters have other concerns as well. That’s why volunteers with the League of Conservation Voters knocked on 2.5 million doors across the country, asking potential voters what matters to them, then explaining how that issue relates to climate change. “You know, we’re trying to tell them what’s important — it might matter, but it’s usually a lot less effective than asking someone what they care about,” said Pete Maysmith, senior vice president of campaigns at the environmental advocacy group. About 75 percent of voters the group spoke to say they plan to vote for Harris, who has the League of Conservation Voters. endorsed.

The group is also making an effort to reach voters online, partnering with TikTok personalities to reach younger voters and creating digital ads that appear on platforms like Hulu and YouTube. One TikTok video features the “Queen of WaterTok” bake macarons emblazoned with Kamala Harris’ face as he talks about the vice president’s efforts to tackle pollution. In a totally different approach, a new digital advertising shown to voters in Georgia and North Carolina in the wake of Hurricane Helene conveys the stakes of the presidential election by illustrating how climate-enhanced storms could threaten babies born today. While you usually have through a fire, flood, or hot weather only a minor effect on how people voteis it possible for a disaster to make a difference in a close race.

The Environmental Voter Project has another method of pushing climate-concerned voters to the polls. The group hasn’t endorsed a candidate, and they don’t talk to voters about climate change at all. Instead, the group uses tactics rooted in behavioral science to get people to cast their ballots, using the power of peer pressure — like mailing people their voting history and reminding them that it’s public record. They also asked voters how they intended to vote — early, by mail or by Election Day — by phrasing the question to sidestep the option of not voting.

“All we’re trying to do,” Stinnett said, “is change someone’s behavior, rather than their mind.”