ohff the west coast of GreenlandA 17-meter (56-foot) aluminum sailboat crawls through a narrow, rocky fjord in the Arctic twilight. The research team on board, still bleary-eyed from the rough nine-day passage across the Labrador Sea, lower nets to collect plankton. This is the first time that anyone has sequenced the DNA of the small marine animals that live here.

Prof Leonid Moroz, a neuroscientist at the University of Florida’s Whitney marine laboratory, watches the nets with palpable excitement. “This is how the world looked when life began,” he says to his friend, Peter Molnar, the expedition leader with whom he Ocean Genome Atlas Project (Ogap).

Moroz gestures to Greenland’s glacial valleys. The rapid warming here replicates conditions of 600m years ago, when complex life forms began to appear. “We are currently sailing through deep biological time,” he says.

Moroz and Molnar’s mission is to classify, observe, sequence and map 80% of the ocean’s smallest creatures to learn more about ourselves and the health of the planet.

At first glance, plankton and humans do not have much in common. But studying marine organisms has led to breakthrough understanding about our own brains and bodies. Observing the electrical discharges of jellyfish taught us how to restart the heart. Sea snails have shown us how memories form. Squid taught us how signals spread between different parts of the brain. Horseshoe crabs have demonstrated how visual receptors work.

An unusual aspect of Moroz and Molnar’s research voyages is that they unlock plankton’s secrets on board sailboats rather than engine–powered vessels – and they are not alone in this endeavour.

“Large oceanographic vessels can cost $100,000 [£77,000] a day, which can quickly bankrupt your research organization,” says Chris Bowler, an oceanographer at France’s National Center for Scientific Research and a scientific advisor to the Tara Ocean Foundation.

He has taken plankton samples for the past two years Microbiome Missiona research initiative to study microorganisms in the sea, on board a 33 meter long schooner. “Working from a sailboat is 50 times cheaper,” says Bowler.

That cost savings also allows researchers the luxury of time, which is essential to finding the genetic communities and patterns that will reveal answers about human health. Bowler says it is important to analyze and observe these microscopic organisms interacting with each other and the world around them. This cannot happen in a laboratory on land because the organisms are too fragile.

Low-carbon, readily available and easier to maneuver close to shore, sailboats “also don’t vibrate, so you can do very precise work on board,” says Molnar, who has captained Ogap voyages over 9,000 nautical miles.

The reason microscopic sea life can teach us about our own development is convergent evolution. This is when unrelated organisms arrive at the same solution to a problem, such as how birds, beetles, butterflies and bats all adapted to fly, but did so at different times and in slightly different ways. Overlapping solutions provide common building blocks for everything from how to fold a protein to how to shape a brain.

“Every organism living here today is a log of every single adaptation that made it successful,” says Moroz. “The brain is one of the most complicated structures in the universe. Yet 70% of our knowledge about how the brain works is thanks to marine animals. Without them, many of today’s medicines simply wouldn’t exist.”

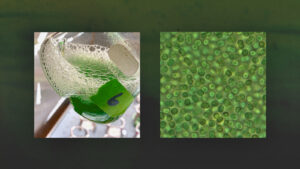

The reason he studies plankton is because their “log” is the longest – some single-celled marine organisms have been around for more than 3 billion years. That means they have more tricks up their metaphorical sleeves than we do.

“Some groups of these marine species do not age, never develop cancer and they can fully regenerate when damaged. They are able to perform many tasks better than us,” says Moroz.

One way to take human medicine to the next level is to take our cues from these organisms. But first we need to identify them. Ogap’s lofty mission would not have been possible 10 years ago; rapid technological advances have reduced the size of equipment, while satellite communications and AI have shrunk the time frame for analyzing results from months to minutes.

In Greenland, for example, Ogap kept marine organisms alive on their sailboat for several days while they sequenced their DNA during different life stages. “We could watch them reproduce, decay, then repair themselves, even die, all while taking high-resolution video,” says Molnar.

The team then uploaded the data via Starlink to universities where scientists used AI to search for pattern recognition in the organisms’ DNA. “Literally within an hour we would have results back on the sailboat,” says Molnar. “This kind of work was just science fiction 10 years ago.”

While the technology is new, using sailboats to explore is a millennia-old human endeavor.

“There’s a long history of sailing to answer scientific questions,” says David Conover, the owner of ArcticEarth, the sailboat Ogap used for his Greenland expedition. From Captain Cook’s anthropological discoveries in the Pacific to Darwin’s ground-breaking observations on natural selection aboard the Beagle, sailboats have given many kinds of researchers the luxury of coming to far-flung parts of the world to engage deeply with their environment.

“The more time you can afford to be at sea, the more open you are to discovery,” says Conover.

The key now is to observe the cornucopia of unknown marine organisms before they disappear forever. “By the time you finish your coffee tomorrow morning, between 20 and 100 species will have disappeared forever, including the wonderful solutions provided by nature, which is a great loss for biomedical science,” says Moroz.

To continue documenting the wonders of tiny single-celled sea creatures, Ogap will go along Patagonia, at the tip of South America. Eventually, Ogap’s genomic atlas will be digitized and made freely available, providing a baseline of marine biodiversity as well as valuable insights for the development of new medicines.

“Every day is a surprise,” says Moroz. “That’s the best part of all these trips – the level of excitement, of discovery. It is so rich. It’s non-stop.”