Hello, and welcome to the latest edition of Grist’s special series on how climate disasters shape elections. I’m Zoya Teirstein.

I was at an election night watch party in Asheville, North Carolina last week when it became clear that Vice President Kamala Harris’ path to victory had become impossibly narrow. On the drive back to my hotel, I drove around roads that had been cut by Hurricane Helene two months earlier. It will take years for Asheville, Black Mountain, Swannanoa and other hard-hit communities in western North Carolina to recover from that storm. Residents will be counting on the next White House administration to see them safely through this disaster and any others that may strike in the next four years.

As the final ballots were counted, evidence mounted that Donald Trump had swung a significant number of American voters to the right. But political observers pointed out that a handful of the very few counties nationwide that bucked the trend — actually moved further out this presidential election cycle — happened to fall along Hurricane Helene’s path.

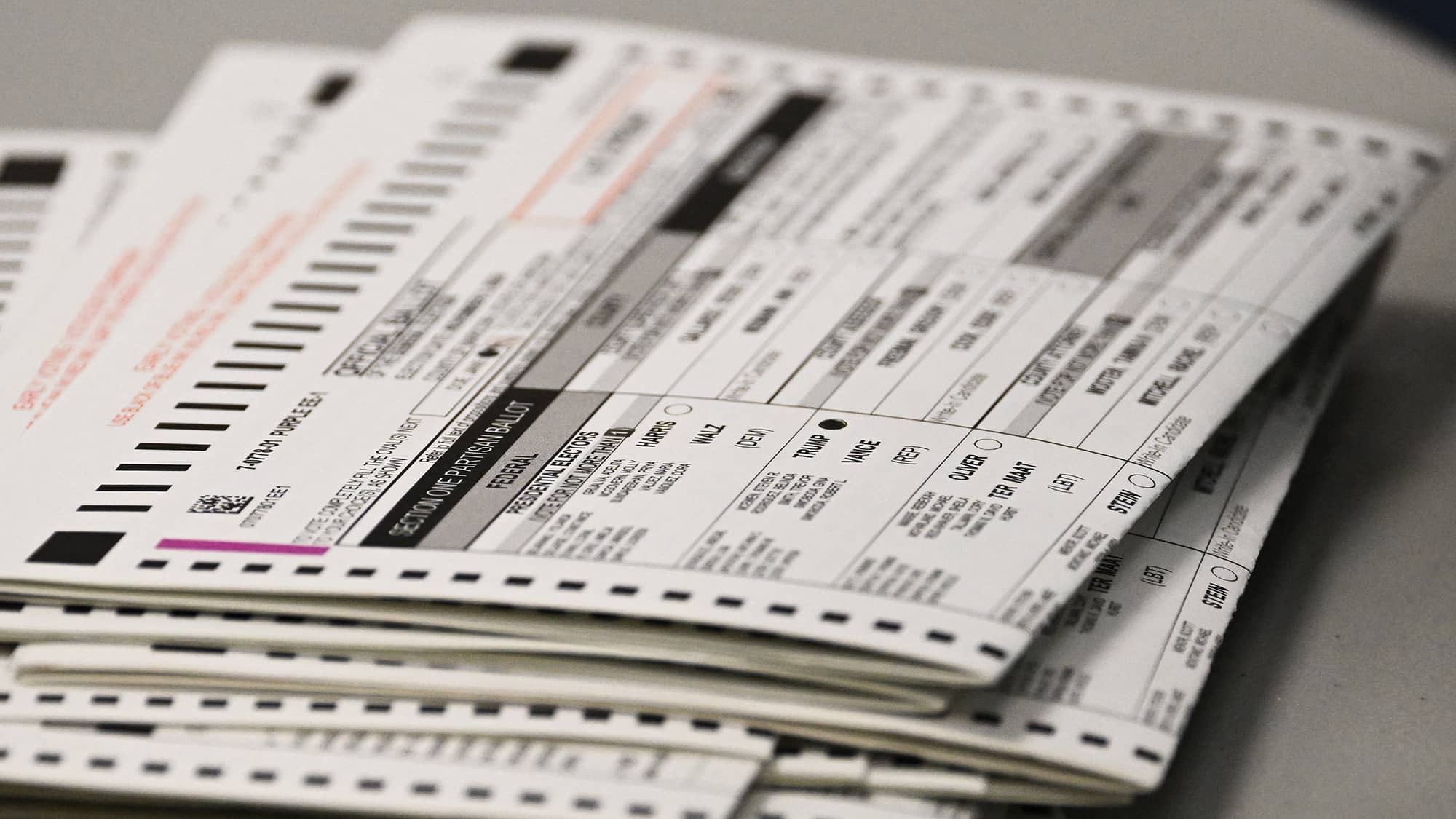

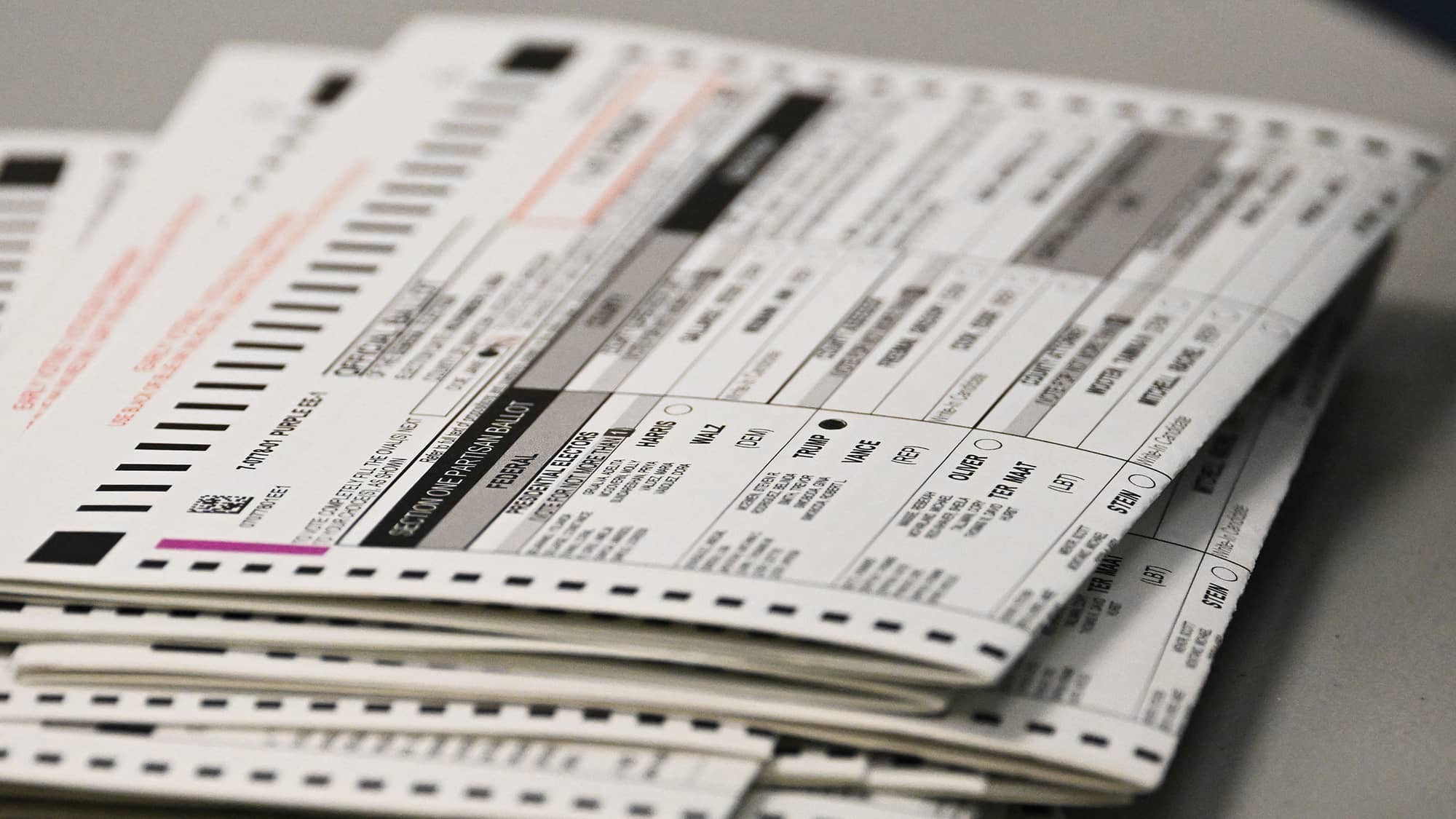

A ballot marked for Trump sits on a stack of completed ballots at the Maricopa County Tabulation and Election Center on Nov. 5 in Phoenix.

Patrick T. Fallon/AFP/Getty Images

Research has shown that people who endure a shock event like a hurricane and then receive a benefit from the federal government tend to vote for the party that provided them that benefit. But experts I spoke with said it’s much more likely that these blue shifts in Helene’s path are explained by factors unrelated to the storm — at least in the short term.

“Remember that a lot of these Appalachian towns that were hit by Helene are really popular places for people to retire,” said Jowei Chen, an associate professor of political science at the University of Michigan. “Trump was less popular among retirees in 2024 than four years ago. So that alone might explain some of the shifts you see in the Appalachian counties.”

However, if there’s one thing I’ve learned over the course of reporting this series, it’s that disasters like Helene have political ramifications that manifest over years, even decades. In July, I wrote about Lake Charles, Louisianawhere a string of back-to-back storms in 2021 fundamentally restructured the city. City councilors, who were elected before the disasters, are still struggling to figure out how many people live in their districts today. On the 19th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina this August, my colleague Jake Bittle wrote about what happened in Houston after an influx of Katrina evacuees reached the city in 2005. Houston’s mayor at the time, Bill White, faced tremendous backlash for helping to resettle those displaced people as a racially charged social panic over alleged gang violence imported from New Orleans spread through the Texas city.

We’ve written about the chaos that ensues for communities that try cast their ballots after a climate-driven disasterthe floods causing housing crisesthe droughts and wildfires that gave rise to a new cadre of solution-oriented politiciansand why a warmer, more volatile planet is a fertile one breeding ground for authoritarianism. “To navigate future climate disruptions, politicians will need to be prepared to deal with concerns about housing, jobs and crime—concerns that may spill over into outright racism or xenophobia,” Jake wrote a few months ago.

The growing chorus of those demanding reform is likely to become deafening—in some places it already has.

The thing is, while Trump and many of the people around him are proud climate deniers, climate change has become almost impossible to ignore. Disasters will continue to tear communities apart; the federal government, no matter who runs it, will struggle to provide the help people need; and more and more disaster victims will become very, very angry. The growing chorus of those demanding reform is likely to become deafening—in some places it already has.

“It’s not just Florida and Louisiana anymore, and it’s not just the states dealing with wildfires anymore,” Vermont’s Republican housing commissioner told me a few weeks ago. “Everyone faces it. We need to completely rethink how we address disasters.”

After collectively traveling to six states and interviewing dozens of people, one thing became clear: We are only beginning to see the political consequences of climate change.

until next time,

Zoya

PS If you would like to see Grist content in your inbox, sign up for our flagship newsletter, The Weekly, and get the week’s biggest climate stories delivered to you every Saturday.

PS If you would like to see Grist content in your inbox, sign up for our flagship newsletter, The Weekly, and get the week’s biggest climate stories delivered to you every Saturday.

PPS This newsletter is part of an annual project at Grist to explore how extreme weather is reshaping our lives. If you want to play a part in shaping next year’s newsletter, fill it out hearing recording. It only takes a few minutes.

PPS This newsletter is part of an annual project at Grist to explore how extreme weather is reshaping our lives. If you want to play a part in shaping next year’s newsletter, fill it out hearing recording. It only takes a few minutes.