For those constantly worried about climate change, the results of the November election seemed to send a clear message: American voters just don’t care as much as you do.

But even as President-elect Donald Trump took the popular vote as he promised roll back the country’s landmark climate legislationthe overall results present a more complicated message. Exit polls show that more Americans have prioritized climate change than ever before. And in several battleground states that supported Trump, Democratic senators who ran on environmental platforms also won their races. Across the country—in blue and red states—environmental ballot measures took hold. So what exactly happened to the climate vote?

“There’s no question that at the presidential level, climate was not on the ballot,” said Pete Maysmith, senior vice president of campaigns at the League of Conservation Voters, an environmental nonprofit. “Voters are complex,” he said. “The economy has really dominated a lot of other issues that have come up.”

Climate change has been largely absent from this presidential election, with both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump remaining relatively quiet on the subject. The National Election Pool, the nation’s largest exit poll, did not include a question on the topic in its survey. But the second largest – a collaboration between Fox News and the Associated Press – did. When asked what they consider to be the most important issue facing the country, 7 percent of the voters said climate change, a nearly doubling of climate concern since 2020, placing it as the fifth most chosen issue out of the nine listed.

“These data show that climate voters have more political power than ever before, even if it’s still not nearly enough,” said Nathaniel Stinnett, the founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project, a nonprofit that tries to persuade environmentalists to vote in the polls. . Among the share of voters who see climate change as their top issue, the vast majority chose Harris — breaking harder for her than any other constituency did for any other candidate. About 9 percent of them chose Trump.

An advocacy group’s message is displayed on a residential lawn in Michigan in November 2024.

Izzy Ross / Grist

But while climate change may not be a top issue for the majority of Americans, that doesn’t mean they don’t care. Environmental initiatives have prevailed across the map: In California, for example, voters sent $10 billion for climate prevention and resilience. In Washington state, a ballot measure to repeal the state’s landmark Climate Commitment Act, which created a cap-and-invest program, failed miserably. In Louisiana and South Carolina, places Trump won handily, conservation funding initiatives received the public stamp of approval.

“Broadly speaking, large majorities of Americans want to take action on climate change, but it’s a high priority for very, very few voters,” Stinnett said. “We’ve seen that play out in a lot of ballot initiatives because when voters are given a binary choice, you either vote for climate leadership or you vote against it.”

While other issues — such as the economy, abortion and immigration — appeared to lead Americans in their vote for president, candidates appeared to capitalize on voters’ climate concerns in the battleground states that swung to Trump, such as Arizona, Nevada, Wisconsin and Michigan. Exit polls show that at least three incoming Democratic senators — Arizona’s Ruben Gallego, Nevada’s Jacky Rosen and Wisconsin’s Tammy Baldwin — won more than 90 percent of the vote from voters who prioritize climate change.

Early voting provided another clue of where the climate vote went in these states. In Arizona and Nevada, environmentalists turned out in numbers large enough to propel Democratic candidates to slim margins of victory. Gallego won his Senate seat by about 80,000 votes — a fifth of the number of early ballots cast by voters who prioritize environmental issues, according to data provided by the Environmental Voter Project. In Nevada, the organization found a similar relationship between early climate first voters and the number of votes Rosen won.

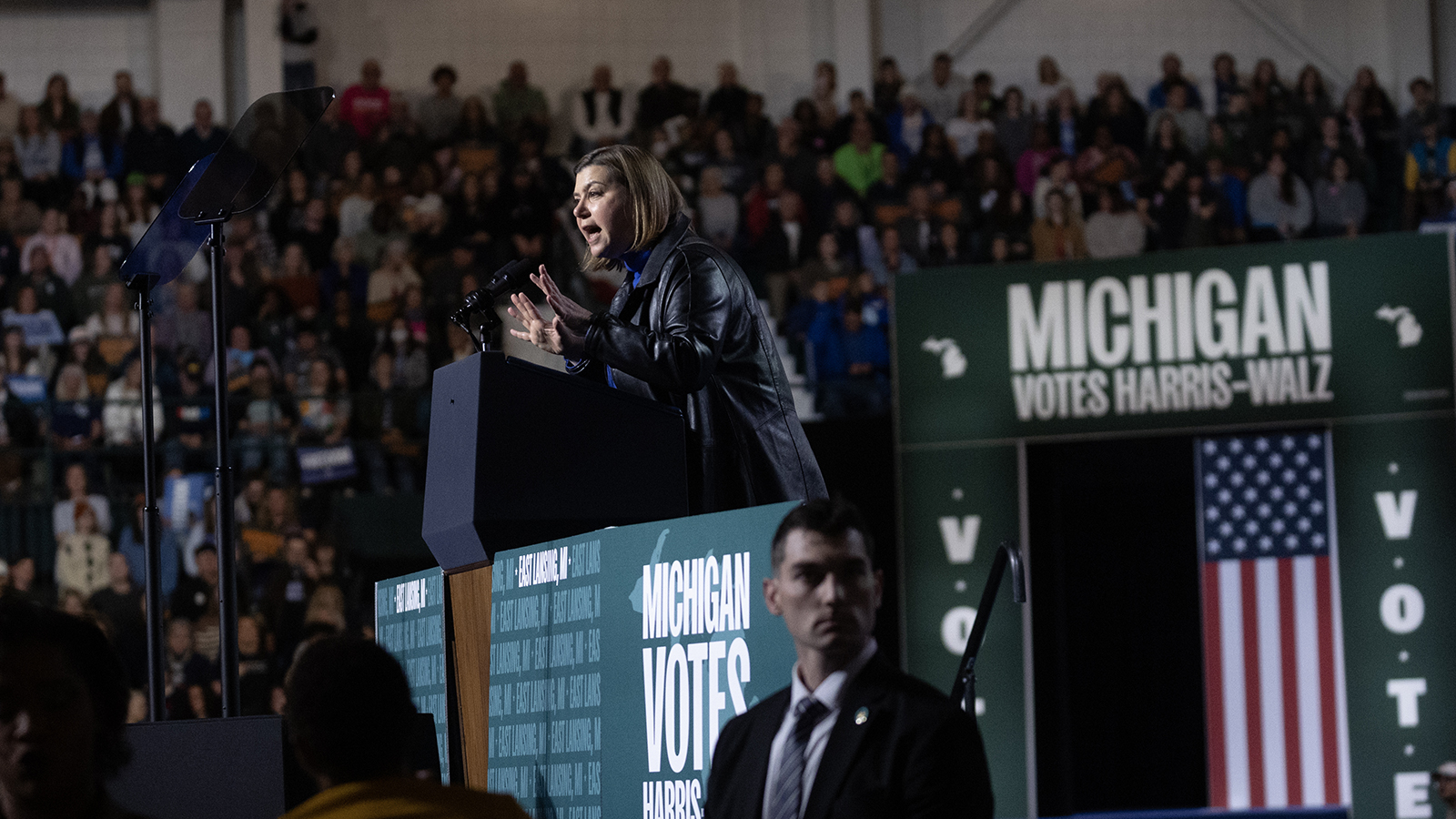

Democratic Senator-elect Elissa Slotkin speaks at a rally hosted by Democratic presidential nominee U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris on the Michigan State University campus two days before the 2024 election.

Scott Olson/Getty Images

And in Michigan, which Trump carried by a slim margin, economic concerns collided with climate action. There, Democrat Elissa Slotkin won a Senate seat over Republican Mike Rogers, who campaigned against Slotkin’s support of the state’s burgeoning electric vehicle industry. tens of millions of dollars on attack ads.

“There are going to be political consequences when you mess with people’s livelihoods,” said Lori Lodes, the executive director of Climate Power, an advocacy group. Lodes believes that a shift to clean energy technologies, such as EVs, will continue – even in red stateswhich benefited more from funding from the Inflation Reduction Act than blue ones. “Democrats and Republicans know firsthand the impact of these investments on their communities,” she said.

There is evidence and precedent to suggest that climate progress will continue regardless of the outcome of the presidential election. About 28 percent of the roughly 400 state-level bills to cut carbon emissions from 2015 to 2020 — which includes the years Trump was last in office — passed by Republican-controlled legislatures. And this summer, 18 House Republicans signed a letter against rolling back clean energy tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act. Exit polls showed that 24 percent of voters who support the expansion of clean energy alternatives to oil and gas also chose Trump.

“Long-term sustainable climate progress must be bipartisan,” said David Kieve, president of Environmental Defense Fund Action, an organization that supports environmental candidates, including Republicans who support their mission. “I don’t think we can continue to operate in the really divided, fractured way that we’ve had in recent years.”