In October, the Bureau of Land Management finalized a new resource management plan for Colorado’s Western Slope that will determine how 2 million acres of public land are managed for the next 15-20 years.

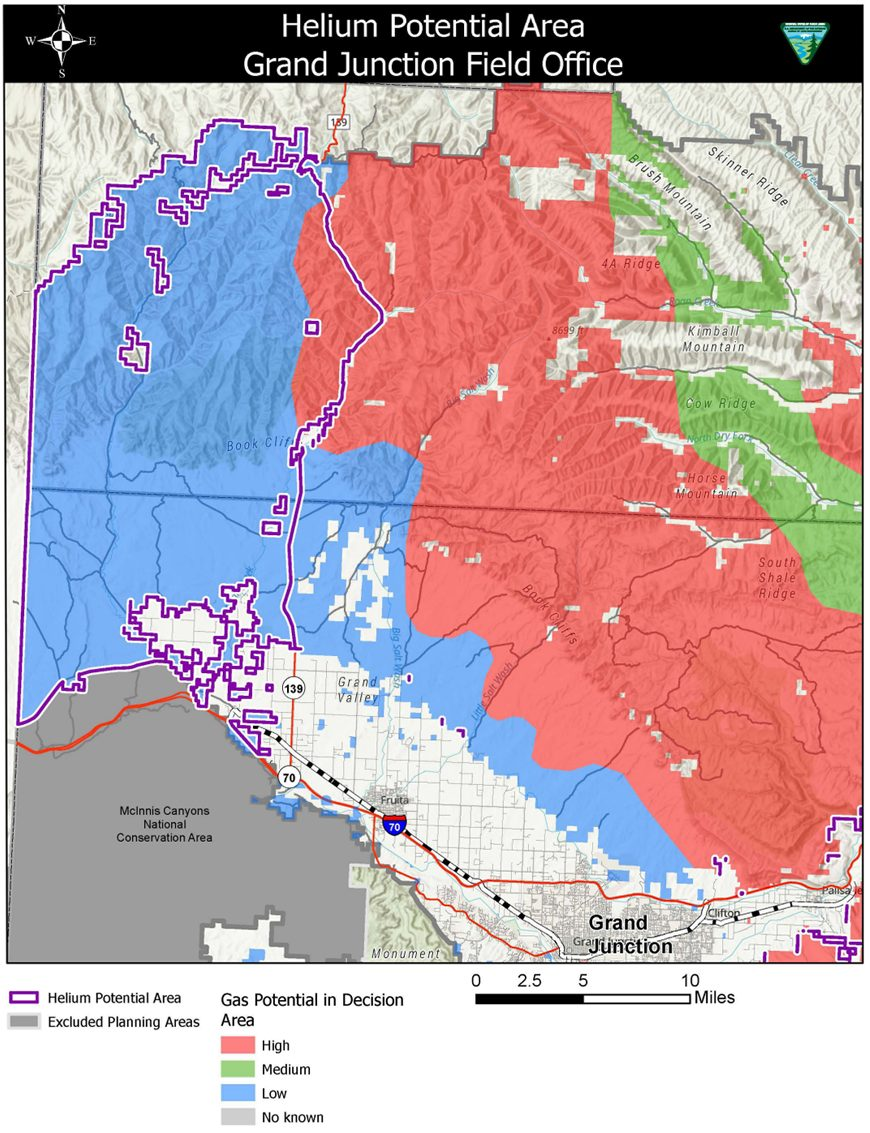

The plan includes some conservation wins; for example, it sets aside land designated as critical habitat and introduces extra protection for big game. But it also allows continued leasing in areas that have moderate and high potential for oil and gas development – with a specific focus on locations with the unique geological conditions necessary for helium production.

Helium is a noble gas, which means that it is chemically inert and does not react with other substances. These properties mean that it is in high demand for a variety of critical uses in medical technology, diving and national defense; diagnostic procedures such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), for example, and nuclear detection systems, including neutron detectors, all depend on helium. Currently, there are no synthetic substitutes for the gas that can replicate its low boiling point and low reactivity.

While some helium is being reused in some scientific areas, the wider adoption of recycling is still limited by cost and infrastructure barriers. Some biotech companies are developing helium-free MRI systems and systems that use helium recovery units, but helium remains an essential resource that many technologies require. And the world’s supply of the gas is rapidly dwindling.

Luna Anna Archey/High Country News with support from EcoFlight

This scarcity has placed increasing pressure on federal public lands to produce a resource vital to industry and national security. Helium is not recyclable: Once released, it escapes into the atmosphere and eventually into space. According to the BLM, it is “a non-renewable resource found in recoverable amounts in only a few places around the world; many of these are being depleted.”

In its final plan for western Colorado, the BLM proposes to close 543,300 acres in the Grand Junction Field Office to oil and gas leasing, but to keep 692,300 open, including about 165,700 acres identified for helium recovery . A BLM spokesman said the nation’s dwindling helium reserves influenced the management plan: “The final decision on this plan to keep the helium area open for future leasing was based on helium’s scarcity and strategic importance.”

Keely Meehan, policy director for the Colorado Wildlands Project, a nonprofit focused on protecting public lands managed by the BLM, criticized the plan for prioritizing resource extraction over preserving critical habitat.

“The environmental impacts and the impacts on habitat and species are the same as for oil and gas,” Meehan said. “It disrupts habitat connectivity.”

The sensitive areas in question include migration corridors and seasonal areas that are essential for species such as mule deer, elk, pronghorn and bighorn sheep, as well as habitat that the endangered Gunnison sage-grouse relies on for breeding, nesting and feeding.

According to the US Geological Surveythat conducted a survey of helium resources across the country, there is plenty of recoverable helium available—about 306 billion cubic feet, or about 150 years’ supply at the 2020 U.S. production level, which comes to about 2.15 billion cubic feet annually . It’s unclear how much of that helium is found on federal public lands. Helium tends to occur naturally in natural gas reservoirs, and since federal public lands in the West account for a significant portion of natural gas production, much of the US’s helium reserves likely reside on public lands.

Some rural communities in western Colorado, many of which have historically depended on resource extraction, welcome the prospect of continued helium production. The Associated Governments of Northwest Colorado (AGNC), a council of city and county governments in that part of the state, advocated opening the area to helium mining in public comments to the agency, citing the potential economic advantages.

“Helium holds significant economic potential and could potentially serve as an essential resource to support communities grappling with looming economic challenges,” the AGNC wrote in the commentary.

However, other communities disagree, and the plan highlighted the ongoing tension between rural communities that depend on resource extraction and those that rely on outdoor recreation, such as Pitkin and Eagle counties. The Mountain Pact, a coalition of local elected officials from more than 100 mountain communities with outdoor recreation-based economies, argued in public comment that leaving the helium leases open would be detrimental to the natural resources that attract tourism dollars and investment.

“Protected public lands are tremendous assets for Western Colorado communities,” the Mountain Pact wrote in a public comment to the BLM. “They play a critical role in our way of life. They help make the communities we live in what they are while contributing to a healthier and better tomorrow for future generations.

In addition to the land impact of helium production, which mirrors that of natural gas extraction, opponents have also raised concerns about processing. Helium is separated from natural gas by a cryogenic process that uses refrigeration and pressure changes, which requires energy, often from natural gas.

However, western Colorado does not currently have a facility that can process helium, and conservationists fear that building one, along with the necessary roads and other infrastructure, would disrupt wildlife habitat and potentially remove some parcels from consideration for future wilderness protection .

“We’re really concerned about these wild places,” Meehan said, “and protecting areas that are currently undeveloped. There are really high-priority wildlands in this area, as well as high-priority habitat.”