Recent data analysis by a human rights advocacy organization found that nearly a dozen international financial institutions directed more than $3 billion to animal agriculture in 2023. The majority of those funds — more than $2.27 billion — came from development banks and went to projects supporting factories. farming, a practice that contributes to greenhouse gas emissions as well as loss of biodiversity.

The researchers behind the analysis call on the development banks – which include the International Finance Corporation, or IFC, part of the World Bank – to assess the climate and environmental impacts of the projects they finance, especially in light of the World Bank’s climate pledges , to investigate. .

The analysis comes from the International Accountability Project, which reviewed disclosure documents from 15 development banks and the Green Climate Fund, which was established at COP16 in 2010 to support climate action in developing countries. Researchers found that 10 of those development banks, as well as the Green Climate Fund, financed projects that directly support animal agriculture. The data serves as the basis for a new white paper from Stop Financing Factory Farming, or S3F, a coalition of advocacy groups seeking to stop development banks from financing agribusiness, released last month.

The International Accountability Project, which campaigns for human and environmental rights, hopes its findings will push international financial institutions such as the World Bank to see the contradiction in financing industrial animal agriculture projects, while also promising to help reduce harmful greenhouse gas emissions .

Agriculture accounts for a significant portion of global greenhouse gas emissions, so much so that research has suggested limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). is not possible without changing how we grow food and what we eat. Within the agricultural sector, livestock production is the main source of greenhouse emissions – as ruminants such as cows and sheep emit methane into the atmosphere whenever they bulk.

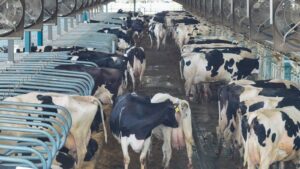

Factory farms, which aim to produce large quantities of meat and dairy as quickly and cheaply as possible, present a problem for the climate and the environment. They can like anywhere hundreds to hundreds of thousands of animals (less if the animals are larger in size, such as cattle, and more if they are smaller, such as chickens). These operations result in enormous amounts of manure, which, depending on how it is stored, can polluted waterways or release ammonia into the air. They also contribute to global warming: A non-profit research organization once looked at the 20 meat and dairy companies responsible for the largest amount of greenhouse gas emissions and found that, together, their emissions surpassed those of countries such as Australia, Germany and the UK

The primary purpose of development banks is to provide funding for projects in developing countries that help achieve some social or economic good. In recent years, these banks have included climate among their considerations when choosing initiatives to support. In his Climate Change Action Plan for 2021 to 2025, the World Bank has declared its commitment to funding “climate-smart agriculture” with the aim of pushing the agricultural sector towards lower emissions without sacrificing productivity. The plan says the IFC, a member of the World Bank Group that funds private sector projects in developing countries, will seek to finance “precision farming and regenerative” agriculture, but also “make livestock production more sustainable.”

But this framework has not stopped development banks from supporting industrial animal agriculture – despite the abundance of information about how factory farming harms people, the planet and animals themselves. “I think it’s just business as usual,” said Alessandro Ramazzotti, the International Accountability Project researcher who led the data analysis.

To determine how much money development banks send in the form of loans, investments and technical and advisory services to industrial animal agriculture projects, Ramazzotti used a tool that scrapes bank websites for public disclosures. From there, he and a team of researchers analyzed the information collected, identified 62 animal agriculture projects, and carefully read the disclosures for detail about each one. They found that of the $3.3 billion spent on animal agriculture, $2.27 billion — or 68 percent — was spent on projects that support industrial animal agriculture or factory farming.

Only $77 million – or 2 percent – went to non-industrial operations or small-scale animal agriculture. The remaining project disclosures did not contain sufficient information for the researchers to somehow determine what kind of initiative it was funding.

RAUL ARBOLEDA / Contributor / Getty Images

Ramazzotti noted that the analysis was subjective based on the interpretation of the language of bank disclosures — which, he pointed out, could largely be considered marketing material for the banks. As a result, projects that sound small in scale can sometimes still veer into industrial animal operations.

He gave the example of the World Bank, which has striven to do so over the years connect small farmers in Latin America to greater market opportunities. Depending on the exact context of such investments, this could be “quite worrying”, he said. For example, supporting small-scale cattle farmers in Brazil could eventually lead to an increase in the supply of beef for the Brazilian meat processing giant JBS SA, which works with suppliers in the region. Such a development would be of concern to environmentalists, such as Livestock farming is considered a major driver of deforestation in the Amazon. JBS, along with three smaller slaughterhouses, was sued by Brazilian authorities last year for allegedly bought illegal cattle on protected lands in the Amazon. JBS declined to comment for this article, but previously said it was “committed to a sustainable beef supply chain.”

The IFC, the member of the World Bank Group that finances private sector projects in the developing world, told Grist that its goals relate to “food security, livelihoods and climate change.”

“There are 1.3 billion people whose livelihoods are linked to livestock and we also know that this sector is responsible for more than 30 percent of global GHG emissions,” said a spokesperson for the member bank, with ‘ an abbreviation for greenhouse gas.

The spokesperson added that the bank seeks to finance projects that increase both livestock production and efficiency, while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The IFC also noted that from July 1, 2025, all of its investments will be required to be in line with the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), and that it will grant recipients of livestock financing to comply with their countries’ obligations under the Paris Agreement.

Lara Fornabaio, a senior legal researcher at Columbia University’s Center for Sustainable Investment, said she was “not surprised at all” by the findings of the S3F report. She argued that development banks, rather than being profit-motivated, should consider the big picture when choosing the types of projects they fund. But she also emphasized that banks must be rigorous when determining whether an initiative fits their stated climate goals.

Even the “reduction of emissions” rubric is probably not strict enough to ensure banks don’t inadvertently support industrial agriculture, Fornabaio said. In some factory farming environments, because producers are so efficient at producing livestock, “the emissions per animal are probably lower than the emissions from a cow [grazing] on a field,” she said. This is partly because farmers in industrial agriculture operations can control every aspect of an animal’s feed – and some feed choices can help reduce ruminant methane emissions. But because large animal agriculture operations raise so many animals, their cumulative emissions footprints can be enormous. This big picture fits research that says shifting diets away from meat is crucial to limiting global warming.

Ramazzotti says his team will continue to monitor bank disclosures for new financing of animal agriculture and hopes to release updated findings on a regular basis in the future. He mentioned that the S3F coalition would consider supporting animal agriculture in the developing world if it was done on a local, small scale – such as through family farms or pastoral or indigenous communities. However, he said the coalition would prefer to see development banks spend money on vegetable farming and plant-based diets.

Ramazzotti is hopeful about the possibility of putting pressure on financial institutions to stop supporting factory farming. Recently, the team found that the IFC had a loan of up to $60 million to expand a company’s meat processing operations in Mongolia. “This is a direct investment in the expansion of factory farming,” he said. “And this is exactly the [type of] investments that we no longer want to see, because we believe that the impact on the local level, but also on the global climate, is very deep.”

The coalition reached out to the IFC team considering this project with concern, and the team has since twice postponed a discussion of the project with their board, according to Ramazzotti. Ramazzotti said that this is not always effective, but he is optimistic that engagement with financial institutions can still lead to change.

Fornabaio agreed. “If I didn’t believe in change, I probably wouldn’t be doing this job. … There’s always a way to apply pressure,” she said. “I think this type of work is key.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled Lara Fornabaio’s last name.