2023 was characterized by symbiosis between the labor and climate movements. Workers across industries and geographies have vociferously declared that a world in which their safety and well-being are disregarded is even more dangerous to them and to others at a time of energy transition and climate crisis. After decades of hesitation, several major unions have recognized an urgent need to organize those who will do the hard work of degassing the nation’s economy. It doesn’t hurt that public sympathy and policy have become kinder to them. As a result, calls for a just transition rattled union halls and corporate offices, as organized labor enjoyed one of its most active years in recent memory and environmental organizations, long unsure of where unions stood, found new allies.

“The choices and solutions aren’t really going to work unless labor is involved,” said Dana Kuhnline, director of Reimagine Appalachia. It works with union leaders and environmental grassroots groups to bring good jobs to coalfield communities that need them. “I think that’s a lesson that climate activists really need to take to heart.”

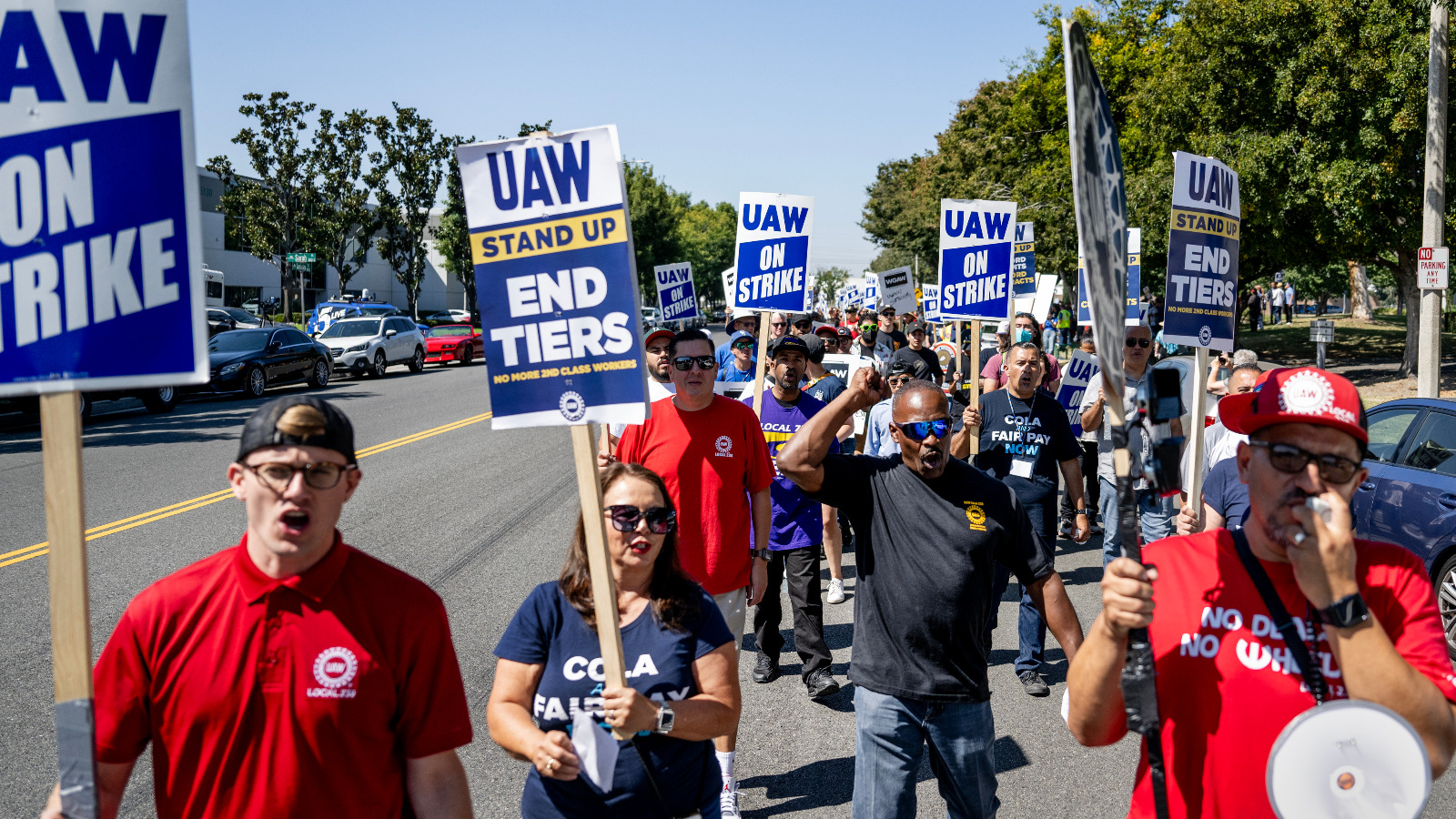

The reality of a warming world was a central concern for UPS, Amazonand airport workers who demanded and in many cases won concessions to protect them from extreme heat. But the biggest gains were made by the 150,000 members of the revived United Auto Workers, or UAW, which made a fair transition a key demand in one of the most high-profile strikes of the year. Although the union’s primary demands concern wages and sick days, no small amount of negotiation has focused on the impending transition to electric vehicles. Workers wanted to ensure that the factories that would make this happen for Ford, General Motors and Stellantis would be union shops, with wages and benefits equal to those provided at traditional auto factories. Forty years of internal organizing brought UAW to a place where it was willing and able to address energy transition, whereas in previous years its leaders had become confused by the idea.

Auto workers were right to be concerned. Many of the sectors making decarbonization happen are not unionized (this is especially true of Asian and European automakers with factories in the United States). Salaries also run lower on average than those paid by fossil fuel industries, where good pay and benefits were hard won, often with union contracts written in the blood of workers from more controversial times. Still, many workers in those fields remain leery of the coming changes — California oil workers, for example much less supportive of policies supporting the energy transition. That’s why many labor experts saw it as a big deal when the UAW overwhelmingly approved a contract that would deliver higher wages, secure its members a role in the EV transition, and potentially lead to greater unionization of the auto sector .

“The UAW strike showed the vision that many people were looking for,” said J. Mijin Cha, an environmental studies professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “The way you have power is through money or through people. We will never have as much money as the fossil fuel industry, so we need people.”

It also gave a public face to work that happened throughout the year in meetings and negotiations between unions, climate activists, public officials and employers. In many of the nation’s fossil fuel communities, clean energy projects — often supported by federal incentives to employ union workers — have embraced organized labor. In West Virginia, for example, the United Mine Workers and United Steelworkers have contracts with battery factories. Solar Hollerwhich will install photovoltaic panels throughout the state, is working with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers to create apprenticeship pathways and some long-term job stability.

Labor leaders and climate organizations are jumping at the possibility that a skilled workforce with a strong training pipeline could bring jobs to struggling fossil fuel communities. Union involvement, they said, would ensure those jobs stay local, instead of going to an out-of-state contractor, and offer competitive wages.

“Our biggest concern is local hiring, and getting the people affected by this economic transition off coal,” said Beau Hawk, who works for the International Brotherhood of Teamsters with an organization called Labor at the Table. It strives to represent labor interests and ensure that funding from the Inflation Reduction Act and bipartisan infrastructure legislation is spent in the communities where it is most needed. He said the organization hopes to build a solid apprenticeship infrastructure and ensure long-term job security that will boost communities in which the instability of the fossil fuel industry has left huge gaps.

Environmental organizations have supported speech for labor this year, with Sierra Club, Greenpeace and others supporting the UAW’s calls for a just EV transition and fame union contracts in the energy transition space as they advocated for climate policy.

“We need both movements to create pressure and we need legislative changes to really capitalize on that,” Cha said.

As the excitement of the year wanes, Cha says, the only way to codify labor’s victories is to increase funding to the National Labor Relations Board and integrate labor standards into the green energy buildup. While the IRA strongly encourages the use of unionized labor for federally funded infrastructure projects, incentives are not the same as mandates. Michigan has taken some steps in this direction, with Governor Gretchen Whitmer issuing a policy package which created an energy transition office and guaranteed union jobs for clean energy workers.

Without such action, Cha said, many unions — which represent many of the carpenters, welders, electricians and other laborers desperately needed in the race to build the infrastructure of the energy transition — may not trust the renewables industry to not provide them. .

Meanwhile, United Auto Workers is setting its organizing sights on 13 automakers that have so far been resistant to union campaigns. Even as the UAW announced its victory last month, Toyota factories in Kentucky and Alabama had already raised their base wages to $28 per hour. A nascent union drive began to turn Tesla, a notorious union buster. Hyundai, which operates electric vehicle battery plants in the South, said it would increase the factory payment starting next year. Solar workers in New Jersey, fed up with unstable, seasonal labor and low pay, asked the UAW for help. “These are the jobs of the future,” the effort’s leaders wrote in a op-ed. They are voting on their union this week.

UAW President Shawn Fain visited Chattanooga, Tenn., on Monday to support a renewed campaign at Volkswagen, where two failed unionization efforts have cast doubt on labor’s chances at foreign automakers in the South. Thirty percent of VW employees signed, a move said to have been met with intimidation by the company, and Fain delivered a letter to management indicating it was on notice for illegal union-busting. This is consistent with the tough and ambitious tone the UAW has adopted this year.

“We may be foul-mouthed, but we are strategic,” Fain said in October. “We may be fired up, but we are disciplined. And we may get rowdy, but we are organized.”