1. India’s lunar lander reaches the dark side of the moon

While western billionaires were busy sending rockets to space only for them to crash and burn, scientists in India were quietly doing something no one had accomplished before. Their Chandrayaan-3 moon lander was the first mission to reach the lunar south pole – an unexplored region where reservoirs of frozen water are believed to exist. I remember my heart soaring when images of the control room in India spread around social media, showing senior female scientists celebrating their incredible achievement.

The success of Chandrayaan-3, launched in July 2023, showed the world that not only is India a major player in space, but that a moon lander can be launched successfully for $75m (£60m). This cost is not to be sniffed at but it is much cheaper than most other countries’ budgets for a moon mission.

July 2023 was an extremely busy month for space firsts. It kicked off with the launch of the Euclid satellite, designed to explore dark matter and dark energy in unprecedented detail. Only a fortnight later, China successfully launched the world’s first methane-fuelled rocket (Zhuque-2), demonstrating a potentially greener way to do space travel, again at vastly reduced cost.

Two weeks after landing, Chandrayaan-3 was sent to sleep during the very cold lunar night-time, only to never wake up, but it had done what it had been sent to do: to detect sulphur on the surface of the moon and to show that lunar soil is a good insulator. With greater diversity, lower costs, and greener rockets, it feels like humanity could be on the brink of a new, more accessible era of space exploration. Haley Gomez

Haley Gomez is a professor of astrophysics at Cardiff University

2. AI finally starting to feel like AI

It’s often hard to spot technological watersheds until long after the fact, but 2023 is one of those rare years in which we can say with certainty that the world changed. It was the year in which artificial intelligence (AI) finally went mainstream. I’m referring, of course, to ChatGPT and its stablemates – large language models. Released late in 2022, ChatGPT went viral in 2023, dazzling users with its fluency and seemingly encyclopaedic knowledge. The tech industry – led by trillion-dollar companies – was wrong-footed by the success of a product from a company with just a few hundred employees. As I write, there is desperate jostling to take the lead in the new “generative AI” marketplace heralded by ChatGPT.

Why did ChatGPT take off so spectacularly? First, it is very accessible. Anyone with a web browser can access the most sophisticated AI on the planet. And second, it finally feels like the AI we were promised – it wouldn’t be out of place in a movie, and it’s a lot more fluent than the Star Trek computer. We’ve been using AI for a long time without realising it, but finally, we have something that looks like the real deal. This isn’t the end of the road for AI, not by a long way – but it really is the beginning of something big. Michael Wooldridge

Michael Wooldridge is a professor of computer science at Oxford University and is presenting the 2023 Royal Institution Christmas Lectures, which will be broadcast on BBC Four over the Christmas week

3. Girls doing hard maths

In March, two teenage girls from New Orleans, Calcea Johnson and Ne’Kiya Jackson, presented a new mathematical proof of the Pythagorean theorem using trigonometry at a regional meeting of the American Mathematical Society.

What’s so special about this? Well, in 1940, Elisha Loomis’s classic book The Pythagorean Proposition had a section entitled “Why No Trigonometric, Analytic Geometry Nor Calculus Proof Possible”. Hence, a2 + b2 = c2 can’t be proved using sin2(θ)+cos2(θ)=1.

This is because these two equations have a circular relationship. For example: If A is true if B is true and B is true if A is true, then how do we know that A and B are actually true?

Johnson and Jackson aren’t the first to derive a trigonometry proof for Pythagoras’s theorem. However, their “waffle cone” proof using the sine rule and infinite geometric series showed great creativity and mathematical agility. There are limitations to their approach – it is not valid when ∅=π/4 (45 degrees), for example. But that is fixable.

Last year, Katharine Birbalsingh, the former social mobility adviser to the UK government, was criticised for saying girls are less likely to choose physics A-level because it involves “hard maths”. Johnson and Jackson’s achievement spoke eloquently to the contrary. Nira Chamberlain

Nira Chamberlain OBE is president of the Mathematical Association and a visiting professor at Loughborough University

4. Insights on our earlier migration out of Africa

We are an African species. That broadly means that Homo sapiens emerged on the land that is now Africa, and most of our evolution occurred there in the past half a million years. The rest of the world was peopled when a few left that pan-African cradle within the past 100,000 years. Until recently, this was largely known from the old bones of the long dead. But recovering DNA from those old bones has become fruitful. In October, a study led by Sarah Tishkoff at the University of Pennsylvania showed that the small amount of Neanderthal DNA in living Africans today had entered the Homo sapiens lineage as early as 250,000 years ago somewhere in Eurasia, meaning that we had left Africa several times, and way earlier than thought.

How were these revelations uncovered? By doing something that has been paradoxically overlooked in our studies of our African origins: actually looking at the genomes of African people.

It may seem small, and incremental, but the more we look – especially among people and areas until now vastly under-represented – the more we are going to find about our own story. Adam Rutherford

Adam Rutherford is a writer, broadcaster and lecturer in genetics at University College London. His latest book is Control: The Dark History and Troubling Present of Eugenics

5. The hottest year on record

As the analogy goes, a frog thrown into hot water will save itself. The slow-boiled one doesn’t notice until the temperature reaches lethal levels. 2023 will be the hottest year on record. That record was previously set seven years ago, in 2016. As King Charles said at Cop28, we are becoming immune to what the records are telling us.

The impacts of the heat are mounting. Warmer seas and a warmer atmosphere contributed to events that brought death and destruction at an alarming rate. In Libya, more than 10,000 people died when a flood swept a city into the sea. Fires burned through Greek islands and Canadian forests. Tropical Cyclone Freddy battered communities in east Africa already pummelled by poverty. Drought and heat made some regions uninhabitable.

The good news is, the answers already exist. In the past year, the UK produced more green energy than ever before. AI forecasts began doing work a million human forecasters couldn’t manage, analysing weather and climate data at an unprecedented rate. The Nasa Swot satellite started measuring where all the water is on Earth, helping to prevent future disasters.

Humans think they are smarter than frogs, but we’ll only save ourselves if we realise that we are the frogs, the source of the heat, and the experimenting psychopaths. Hannah Cloke

Hannah Cloke OBE is a professor of hydrology at the University of Reading

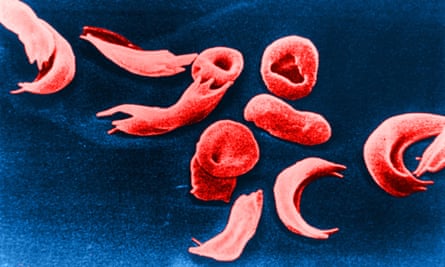

6. New Crispr therapy for sickle cell disease and beta thalassaemia

In recent years, racialised inequities in healthcare have been much publicised. For some, this has reduced trust in health sciences and services, including preventive measures such as vaccines. So it is cause for celebration that the UK is trailblazing a biotechnology therapy for sickle cell disease and beta thalassaemia. These debilitating and sometimes deadly diseases are respectively more likely to afflict black populations and those with roots in the southern Mediterranean, Middle East, south Asia, and Africa. In a world-first, the UK medicines regulator has approved the Crispr–Cas9 genome-editing tool called Casgevy, for the treatment of disease. The therapy has been shown to relieve debilitating episodes of pain in sickle cell disease and to remove or reduce the need for red-blood cell transfusions in thalassaemia for at least a year.

While heartening, it remains to be seen how the potential risks play out. Will the positive outcomes continue in the long term? What of the safety implications? There is, for example, the possibility that Crispr–Cas9 can sometimes make unintended genetic modifications with unknown effect. Equally, this therapy may cost as much as $2m (£1.6m) per person. In setting budgets, will these diseases continue to be a focus?

Yet the approval gives cause for cautious optimism – not least because including groups frequently overlooked could mark a small, but important, shift towards making healthcare more equitable. Ann Phoenix

Ann Phoenix is a professor of psychosocial studies at the UCL Institute of Education

7. Eating our cakes and having our Wegovy

The world has a food problem: 650 million adults are obese, meaning they have a body mass index (BMI) of over 30 kg/m2 and consume more calories than their bodies can use. On the other hand, 735 million people worldwide are starving. However, more people die from being obese than from being undernourished. So the discovery of a group of drugs known as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor stimulants is welcome. These GLP-1 drugs were originally licensed to control diabetes and they have since been licensed as weight-loss medicines. Wegovy, the poster child of these medicines, works by reducing blood glucose and by making people feel full more quickly when eating. In a two-year, 304-person clinical trial, subjects on Wegovy lost 15% of their body weight, while control subjects lost only 3%. Excitingly, this year we have also learned, from a large, three-year study involving heart disease patients, that Wegovy also reduces the risk of strokes, heart attacks and death from heart disease. It may seem as if we can now eat as much as we wish and get an injection for that, but there are side-effects to taking Wegovy, such as nausea, vomiting, headaches, tiredness and a possible risk of developing some thyroid cancers. Additionally, we still need to find a way to feed the starving. Ijeoma F Uchegbu

Ijeoma F Uchegbu is a professor of pharmaceutical nanoscience at University College London

8. A superconductor claim meets resistance

For decades, scientists have been on the quest for the “holy grail” of a room-temperature superconductor. A superconductor is a material that carries electric current without resistance, but this remarkable property is only observed more than 100C below room temperature.

In July came the extraordinary claim from a South Korean team led by Sukbae Lee and Ji-Hoon Kim of the first room-temperature superconductor at normal pressure with a lead-based compound named LK-99. Such a breakthrough could enable loss-free power cables and smaller MRI scanners.

Lee, Kim and colleagues uploaded two papers to the arXiv website, where studies are sometimes posted before peer review. This led to a buzz of excitement and scepticism as labs worldwide rushed to try to replicate the findings, with LK-99 even trending on Twitter (now known as X).

By late August, leading labs had failed to replicate the results. The current consensus is that there is not enough evidence of the crucial signatures of room temperature superconductivity.

What does this story teach us? It shows that careful materials characterisation is essential before rushing to hyped conclusions, and that scientific peer review can be constructive and thrilling. Even if LK-99 isn’t the holy grail, it shouldn’t deter the search for a real room-temperature superconductor, and may open up unexpected pathways for exciting new research. Saiful Islam

Saiful Islam is a professor of materials science at Oxford University

9. Bird decline linked to herbicides and pesticides

This has been a record-breaking year – and not in a good way, when it comes to the environment. Alongside global heating, yet another environmental disaster is unfolding: the rapid loss of wildlife.

Though pressing, the biodiversity crisis receives up to eight times less coverage than the climate emergency. Consequently, even though I am usually a sucker for positive research (such as the rediscovery of Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna, or exploring why primates like to spin round and round), for my pick of the year I chose a study focusing on the decline of European birds.

Over the past four decades, the number of birds across Europe dropped by a staggering 550 million. Thus far it was believed that the main reasons were habitat loss and pollution. But a research team led by Stanislas Rigal investigated data on 170 bird species across 20,000 sites in 28 countries – including records collected by citizen scientists – and concluded that the principal bird killer is agricultural intensification. More precisely, it is an increased use of pesticides and fertilisers, which not only deprive birds of food, but also directly affect their health.

Such large-scale studies are crucial for influencing decision-making and policy priorities. Let’s hope that 2024 brings a positive change in those departments. Joanna Bagniewska

Joanna Bagniewska is a science communicator and senior lecturer in environmental sciences at Brunel University

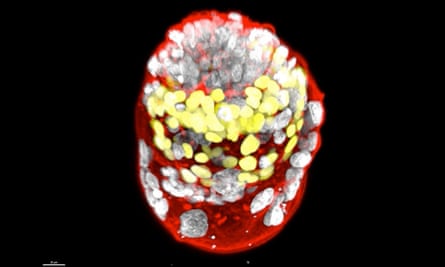

10. Hope for stem cell-based embryo models

There was a flurry of papers and preprint articles in June describing how it was possible to begin with cultures of pluripotent stem cells and, entirely in a culture dish, end up with structures that resemble early post-implantation human embryos. These prompted considerable media coverage, including front-page stories in some newspapers. The science was certainly newsworthy – the experiments reveal a remarkable ability of the stem cells to differentiate into the relevant tissues that self-organise into the appropriate pattern. However, some rather robust competition between several of the groups involved may have also contributed to the media interest.

It is hoped that stem cell-based embryo models will provide a practical and “more ethical” alternative to working with normal embryos. Scientists may be able to learn much about how we develop and what goes wrong with congenital disease, miscarriage, and with assisted reproduction (IVF) that often fails – and perhaps to find solutions to these problems.

What is clear at the moment, however, is that even the best of the models are not equivalent to normal human embryos, and the most rigorous test – to ask if they could be implanted into a womb – is something that everyone agrees should not be attempted. At the moment the vast majority, perhaps 99%, of the aggregates that are put into culture fail to give anything that resembles a human embryo. The efficiency needs to be improved if these models are going to find a use. Robin Lovell-Badge

Robin Lovell-Badge is a senior group leader and head of the Laboratory of Stem Cell Biology and Developmental Genetics at the Francis Crick Institute