This story was originally published by Floodlight, a non-profit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.

In the more than a decade since Alabama regulators allowed a landfill to take in tons of waste from coal-burning power plants around the US, neighbors in the majority-Black community of Uniontown frequently complain of thick air so pungent it makes their eyes burn.

On some days, it can look like an eerily white Christmas in a place that rarely sees snow.

“When the wind blows, all the trees in the area are totally gray and white,” said Ben Eaton, a Uniontown commissioner and president of Black Belt Citizens Fighting for Health and Justice, a local group that is pushing to shutter the facility.

Residents of the former plantation town complain of high rates of kidney failure and neuropathy – two symptoms of exposure to coal ash, whose toxic byproduct contains mercury and arsenic. The controversy has been covered for years in local and national news outlets, including a civil rights case Eaton’s group filed – and lost – to close the landfill.

Michael Malcom/The People’s Justice Council

Just last year, coal ash in the state drew national attention when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) tentatively denied a state clean-up proposal that it found to be too weak for waste coming in part from its largest electricity provider – Alabama Power.

But neither the news from Uniontown, nor the EPA rejection, ever appeared in the Birmingham Times – a historic African American newspaper – or on the online-only Alabama News Center, an investigation by Floodlight found. A search for “coal ash” in the Birmingham Times yields just one reprinted story from HuffPost, and it’s a reference to coal ash in another state.

Both news outlets have financial ties to the main subject of those stories, Alabama Power.

For decades, Alabama Power has sowed influence across the state, according to interviews with more than two dozen former and current reporters, civil rights activists, utility employees and environmentalists.

What’s happening in Alabama is an example of how special interests have taken advantage of the diminishing reach and influence of shrinking mainstream newsrooms in the US. In their place have sprung up fake “pink slime” news sites operated by political interests; a utility that secretly created news outlets to attack its critics; and a Florida publisher who accepts payments for positive coverage.

Lee Hedgepeth/Inside Climate News

This investigation into power companies infiltrating local media follows Floodlight’s revelation earlier this month about how utilities wield influence among civil rights groups.

In the last decade, nearly a dozen local reporters and editors were hired to staff the two Alabama news outlets. A Floodlight review of the content since the utility founded the Alabama News Center in 2015 shows it publishes overwhelmingly positive stories about the power company.

Coverage of the utility by the Birmingham Times, which was funded with money from Alabama Power’s charitable arm the Alabama Power Foundation, consists of reprinted stories from the News Center and the utility’s own press releases.

The Birmingham Times executive editor, Barnett Wright, said the outlet’s coverage is limited due to its small staff and having to make hard editorial decisions on what to cover. “The Alabama Power Foundation had or has zero influence in the newsroom,” Wright said in an email. “As the executive editor, I have never had any conversation with the Alabama Power Foundation about any article the Birmingham Times chooses to run or not run.”

Alabama Power and its foundation did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Michael Malcom/The People’s Justice Council

Here is another example of news that readers of the Birmingham Times and the Alabama News Center do not see: when Alabama Power was granted three consecutive electric rate increases in 2022 – raising the average annual cost of electricity by $274 in 2023 – neither publication wrote about the rise, according to a search of their websites.

Residents of this seventh poorest state have the most expensive monthly electric bills in the US. This past summer – after the increases – Alabama Power customers railed against bills topping $700 a month for some households.

“Clearly those communities that are suffering this way don’t have pleasant things to say about those [Alabama Power] folks who are causing the problems in the first place,” said the Rev Michael Malcom, executive director of Alabama Interfaith Power and Light, a faith-based organization that focuses on climate change. “So how best do you silence these people? You control the narrative in the first place.”

Wright countered that he does not have the staff to “give those rate increase stories the comprehensive cover … they deserve.”

But, he added, “that’s a fair question. Our readers turn on lights, flush toilets, take showers and warm their homes, and it’s a story that should be covered and will be going forward – even if I have to write them myself.”

A ‘good news’ site

The Alabama News Center was launched to promote “the good news of this state.” Its stories run in outlets around Alabama and are picked up by national aggregators including Google and Apple News.

It’s ostensibly news – with an electric industry tinge. Recent top stories include a write up of University of Alabama students competing in an electric vehicle battery challenge and a feature on a career day for future lineworkers.

Lee Hedgepeth/Inside Climate News

The News Center’s operation is entirely paid for by electricity customers, Alabama Power’s assistant treasurer, Brian George, said at a December public hearing.

he electric company’s power over the news in the state is a significant silencer, according to 15 reporters interviewed by Floodlight. They cite Alabama Power’s digital and broadcast advertising purchasing power and its aggressive stance toward reporters and outlets that publish critical stories.

Floodlight previously revealed the company’s secret hiring of an Alabama-based consulting firm to pay for positive news coverage in three other Alabama news outlets. Coupled with its foray into newsroom financing, Alabama Power now exerts a heavy influence on what news is covered or ignored in Alabama.

The effect is compounded by hundreds of layoffs of news reporters in Birmingham, Montgomery, Huntsville and Mobile in the past decade.

“If you just search Alabama Power and Google News, you’re not going to find a lot that’s very investigative or goes beyond the surface level of just covering press releases. There are a lot of factors that go into that, that aren’t just Alabama Power manipulating the media,” said Lee Hedgepeth, an Alabama-based reporter at Inside Climate News.

Alabama’s powerful power company

Alabama Power is a huge economic driver. Its parent company, Southern Co, employs about 27,700 employees, with more than 6,000 working for Alabama Power.

It’s a significant player in the state’s mostly Republican politics. Using heavy lobbying and campaign contributions to utility regulators and politicians, Alabama Power has created strong allegiances that allow it to secure rate hike approvals without public hearings. The company also operates the nation’s dirtiest power plant.

The PJC Media/Michael Malcom

And it places steep fees on homeowners, which stymie the competing rooftop solar industry. The result is that sunny Alabama trails far behind Alaska – which sees only a few hours of daylight in deep winter – when it comes to clean solar energy.

Alabama politicians have in large part allowed the utility to flourish. Shareholders of the publicly-traded utility receive some of the highest returns on equity in the country. In fact, in 2022 Alabama Power reported more profit than allowed, and this past August had to refund $62 million to its customers.

Even before Alabama Power created its own news entities, four reporters in the state said the utility was aggressive in squashing negative news coverage, including frequently challenging reporting by demanding to meet with top newsroom leaders or threatening lawsuits.

In 2001, Birmingham’s FOX6 station killed a story about an elderly woman who died after life-sustaining equipment was turned off in her home when Alabama Power halted her electric service over failure to pay. Three former newsroom staffers who asked not to be named said a station executive – who later went to work for Alabama Power – spiked the story.

The utility later settled with the family for $15 million. The former station executive did not respond to a request for comment.

Two Alabama Political Reporter journalists recounted separate instances of a critical story they wrote about Alabama Power being killed without explanation by their outlet in 2013 and 2021. Each suspected the articles were held to appease Alabama Power. At least as far back as April 2013, the Alabama Political Reporter was being paid $8,000 a month by Matrix, the consulting firm employed by Alabama Power, leaked records show. The site’s publisher didn’t remember the stories and denied they were killed because of the utility.

Utility foundation buys Black newspaper

Founded in 1964 as a paper written by and for the Black community, the Birmingham Times emerged as the state became a leader in the civil rights movement, including the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery march that culminated in brutal police attacks on protesters.

In 2016, the Birmingham Times was sold to the Foundation for Progress in Journalism, a nonprofit established with $35,000 of Alabama Power Foundation money, tax records show. Alabama Power’s charity gave the Foundation for Progress in Journalism $185,000 between 2014 and 2016. The chair of the board for the journalism foundation also was a vice president at Alabama Power.

Michael Malcom/The People’s Justice Council

Birmingham Times publisher Samuel Martin says the paper’s founder at 91 years old had no clear successor and approached the foundation to purchase it. “It was his hope that the Foundation would offer a way to preserve his legacy, with the Times being the only remaining Black newspaper in Birmingham. The foundation agreed,” Martin said in an emailed response.

On the surface, the Times appears to be a typical independent newspaper. It largely publishes profiles and stories about the state’s Black community, sometimes touching on hard topics like gun violence and poverty. A recent issue of the newspaper had a lead story about the city’s Black homeless population. The back of the paper featured a full-page Alabama Power ad. The paper does not disclose its relationship to Alabama Power on its website or in the weekly print edition.

Martin said there is “no reason to reference Alabama Power” on its website or in its paper and stories because “they have no ownership.”

Influencing the Black community has been part of Alabama Power’s playbook for years, Floodlight has learned. In 2018, the utility paid the owner of the consulting firm Matrix LLC $124,000 a month – or nearly $1.5m a year – to maintain ties to Black communities, according to a leaked copy of the contract. One provision called for the Matrix owner to “continue strategic consulting and issue research that promotes [the] Company’s commitment to helping develop the Black Belt region.”

It is also a region, in central Alabama, that suffers from environmental and health impacts linked to coal. Some residents there tape up windows to keep black soot out of their homes.

“By controlling the media, they (Alabama Power) are able to present as good neighbors to the public while drowning out those private conversations that talk about the [environmental] burdens that these communities have to bear,” Malcom said.

Warding off a rate hearing

Alabama Power made its move into newsrooms on the heels of one of the biggest threats to its business model.

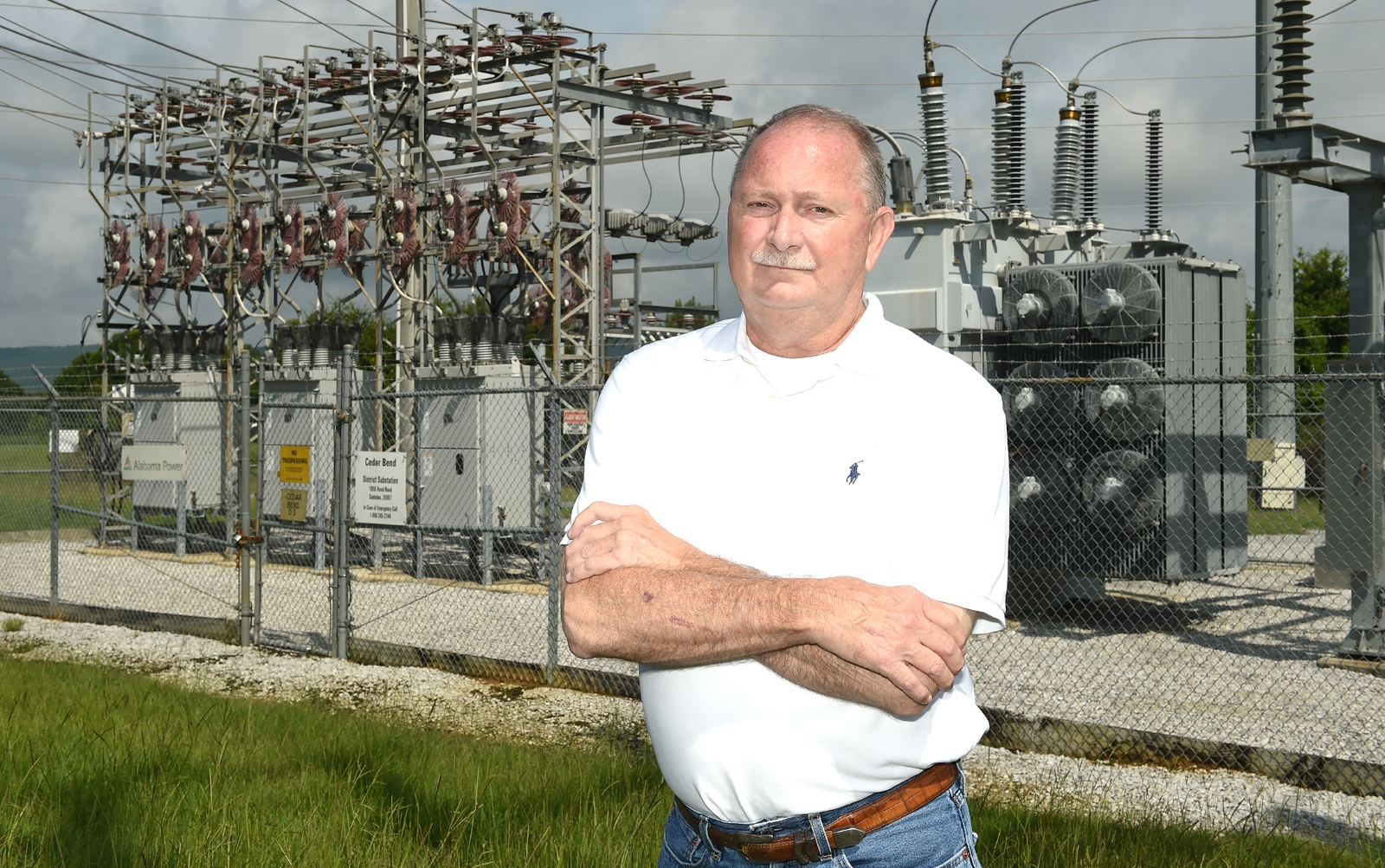

Back in 2013, a Republican member of the Alabama Public Service Commission wanted to know why customers’ bills were so exorbitant. Terry Dunn wanted Alabama Power and two other utilities to open their books and answer questions about how rates were determined.

Joe Songer for Floodlight

It would be the first time in 30 years that Alabama Power was forced to answer to regulators in a formal public hearing.

Dunn’s more-tenured fellow commissioners pushed back. The Public Service Commission president, Twinkle Cavanaugh, who the year before reportedly received nearly $89,000 in campaign donations from coal interests, rejected Dunn’s call for a hearing as “half-baked.”

Around that same time, a non-profit, Alabama Citizens for Media Accountability, launched a website that attacked local reporters who covered Dunn’s arguments and his tight re-election race.

The group said it was “devoted to exposing liberal bias in the Alabama media.” Articles posted on its website often targeted reporters from AL.com, an online conglomerate of Alabama’s three largest newspapers.

“They went after me a lot,” said John Archibald, a two-time Pulitzer prize-winning editorial writer for AL.com who frequently wrote about Alabama Power.

Public tax filings show that Alabama Citizens for Media Accountability was given $100,000 in 2014 from a non-profit directed by Alabama Power consultant Mike Fields. The funding made up nearly its entire annual budget.

Dunn ultimately lost his re-election bid. Six months later, Alabama Citizens for Media Accountability stopped posting, and its executive director, Elizabeth BeShears, left to join Yellowhammer News, which has financial ties to the Matrix consulting firm, as Floodlight and NPR reported in 2022.

BeShears, spokeswoman for a national school choice group, did not respond to requests for comment.

Alabama Power’s ‘brand journalism’

In early 2015, less than a year after Dunn’s defeat, Alabama Power launched the Alabama News Center. Its motive: to bypass news organizations altogether.

Through the News Center, the utility would no longer have to rely on other reporters and news outlets to get their message out, explained Ike Pigott, Alabama Power communications strategist and former broadcast reporter, in a 2016 podcast about the News Center.

Alabama News Center website

“It’s helping establish us as a source of news,” Pigott said. “And when you look at the kind of stories that we do, and the degree of professionalism we take with it, it is news. It’s just not coming from what you would traditionally consider a news-only provider.”

Pigott said in creating its “brand journalism,” Alabama Power looked to fossil fuel giant Chevron for inspiration. Chevron in 2014 was caught secretly running a “community news site” in Richmond, California, that published positive stories – many written by a public relations firm – about oil and gas drilling in the state.

“We were looking at the Richmond Standard, we saw it for what it was,” Pigott told the interviewer. “And we saw it as an opportunity to say, ‘Hey, we can get out and we can tell some of our stories too.’” Pigott did not respond to requests for comment.

Alabama News Center divulges that it’s a product of Alabama Power on its homepage. But it does not do so on its stories that are picked up by legitimate news sites. The News Center operates as a state news wire and also reaches national readers through Apple and Google News, which both treat the site as a regular news outlet.

Regardless of ownership, traditional media outlets are bound to ethics standards that maintain a distance between the business operations and working journalists.

“The easy question to answer is, ‘Are you being transparent? Are you levelling with the public about who you are?’” said Dan Kennedy, a professor at Northeastern University’s School of Journalism in Boston.

“But if they’re doing some extremely favorable coverage of the power company, and any fair-minded person looking at this would say, ‘They’re leaving out important information about what the power company’s doing.’ It simply isn’t ethical to do that.”

Today, Alabama has just a handful of reporters fully devoted to covering environmental and energy issues in the state of 5 million people and the country’s third-largest coal exporter.

“I always regarded doing environmental journalism in Alabama like shooting fish in a barrel. There’s always so much to cover,” said Ben Raines, a former AL.com and Mobile Press Register environment editor who won several national prizes for his stories.

Raines left AL.com in 2019 and now spends his days on documentary projects and giving tours of the Mobile River.

“We have lost the firepower of environmental reporting we used to have. And in place of it, we have almost no coverage.”

Floodlight reporters Kristi E Swartz and Mario Alejandro Ariza contributed to this story.