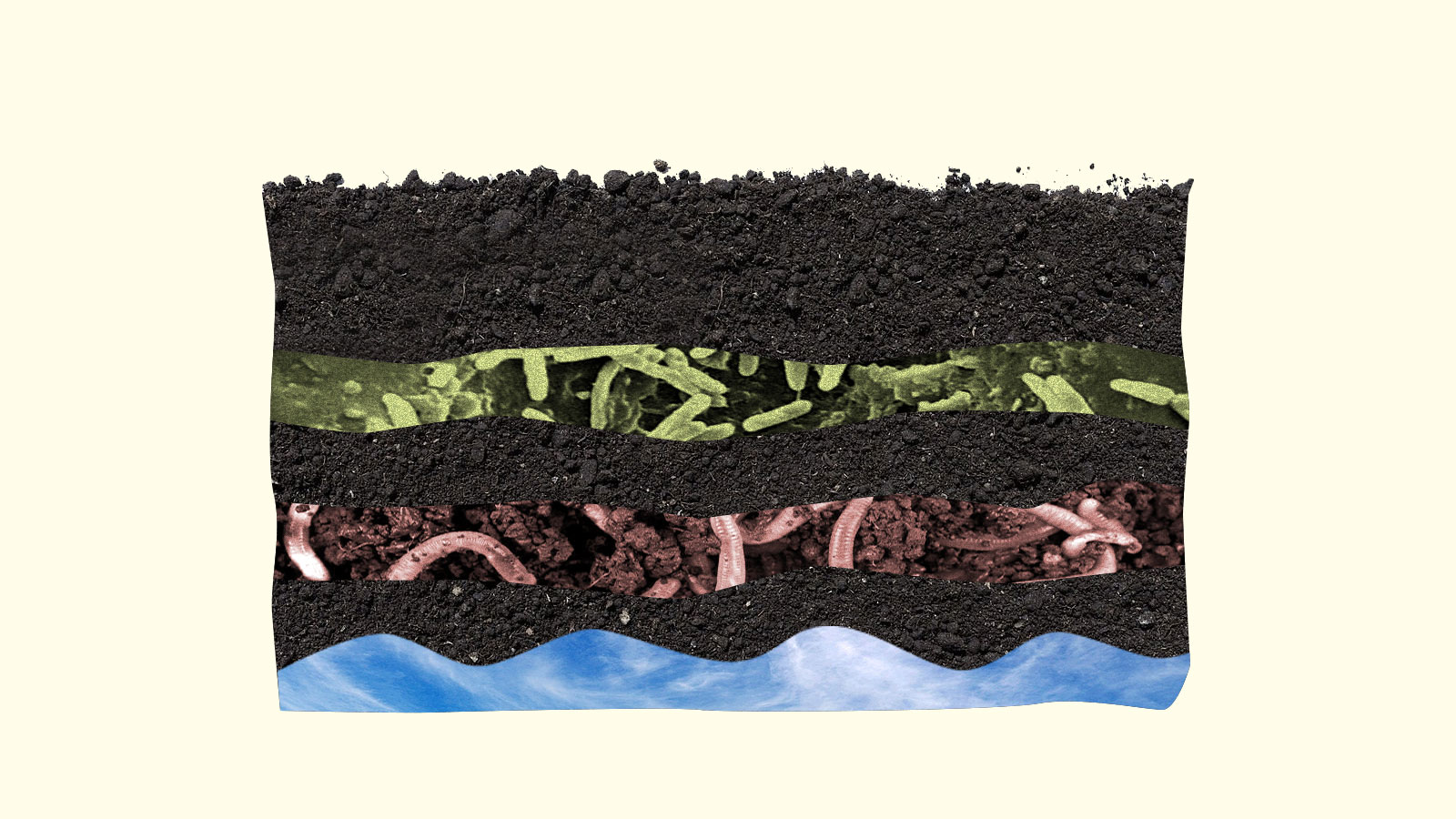

Dirt, it turns out, isn’t just worm poo. It is also an enormous reservoir of carbon, some 2.5 trillion tons of it – three times more than all the carbon in the atmosphere.

That’s why if you ask a climate activist about the US farm bill — the broad, trillion-dollar spending package that Congress is supposed to pass this year (after failing to do so last year) — they’ll probably tell you something about the things below your feet. The bill to fund agriculture and food programs could put a dent in the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, some environmental advocates say, if it does one thing in particular: Help farmers store carbon in their soil.

The problem is, no one really knows how much carbon farmers can store in their soil.

“There’s still a lot of research that needs to be done,” said Cristel Zoebisch, who analyzes federal agricultural policy at Carbon180, a nonprofit that promotes carbon sequestration.

Farmers and ranchers interact with carbon more than you might think. For example, draining a swamp to plant rows of soybeans releases a lot of carbon into the air, while planting rows of shrubs and trees on a farm – a practice called alley cropping – does just the opposite, pulling the element from the air and putting it in the earth. If America’s growers and ranchers made sure that the carbon on their soil stayed under their crops and their cows’ hooves, some scientists say the planet would warm quite a bit less. After all, agriculture is responsible for about 10 percent of the United States’ greenhouse gas emissions.

“We are very good at producing a lot of corn, a lot of soybeans, a lot of agricultural commodities,” Zoebisch said, but farmers’ gains in productivity have come at the expense of soil carbon. “That’s something we can start fixing in the farm bill.”

For more than a year, climate advocates have eyed the bill as an opportunity to increase funding and training for farmers who want to adopt “climate-smart” practices. According to the Department of Agriculture, that label can apply to a range of methods, such as planting cover crops such as rye or clover after a harvest or limiting how much a field is tilled. Wheat farmers can also be carbon farmers.

But experts say the reality is a little more opaque. There’s still a lot scientists don’t know about how dirt works, and they don’t agree on the amount of carbon farmers can realistically remove from the air and lock into their fields.

Zoebisch and other advocates say that for the farm bill to be a true success, it will have to go even further than incentivizing carbon farming. Congress should also, they say, fund researchers to verify that these practices actually remove carbon from the atmosphere.

Currently, there is virtually no good way for a farmer to know how much carbon they are storing on their land. Current techniques for sampling soil and measuring carbon levels are very expensive and require equipment that is difficult to use, Zoebisch said. It’s a lot more complicated than sending buckets of dirt to a room full of scientists. Researchers must drill more than a foot deep into the ground and dig up a ‘core’ which must be handled carefully to avoid compacting or disturbing the soil en route to a laboratory.

“There are so many points where errors can be introduced,” Zoebisch said.

Several companies are trying to make the process easier and cheaper, but new technology has not yet scaled up. Besides taking physical measurements, the USDA uses a model to estimate soil carbon levels based on extremely limited data, and its projections are highly uncertain, so they’re pretty useless at the local level, says Jonathan Sanderman, a soil scientist and carbon program director at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts. “You can’t really say to a farmer: ‘This is the exact benefit’.”

Scientists largely agree that cover crops help sequester some carbon, but exactly how much is up for debate, and it varies by geography, soil type and numerous other factors. Planting cover crops in fertile Iowa may not have the same effect as planting them in the sandy soil of Southern California.

“There’s uncertainty in the literature, but from a first principles point of view it makes sense that cover crops should get carbon because you’re capturing CO2 from the atmosphere — a few tons per hectare — that you wouldn’t have captured” otherwise, Sanderman said. . “It’s the nuance we don’t understand.”

Timothy Searchinger, an agriculture and forestry researcher at Princeton University and the World Resources Institute, said he is a fan of cover crops because they prevent precious topsoil from being washed or blown away and nitrogen from polluting rivers and streams, but he thinks they potential climate benefits – and those of other practices such as reduced tillage – are often exaggerated. Rather than binding on soil carbon, he said the farm bill should focus on making agriculture more efficient. Helping farmers produce more food on existing farmland can save carbon-rich forests and peatlands from being cleared to meet demand for crops and livestock.

However, Searchinger acknowledged that there may be at least some potential to store carbon on farmland and said he doesn’t want the USDA to stop helping farmers who want to plant cover crops or try other “climate-smart” practices.

Congress allocated nearly $20 billion through the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022 to programs that do just that. Some $300 million of it will go to the USDA to step up efforts over the coming years to measure carbon in the soil. Currently, the agency uses long-term data from only 50 sites across the country, Sanderman said. The Inflation Reduction Act funding could increase that number to several thousand.

That money was “an incredible first investment,” Zoebisch said. “It’s going to be great for the next four years of funding. But what happens after that?” Zoebisch and others want to see funding for soil carbon research made permanent in the farm bill.

Fulfilling that wish — and the many others held by climate advocates — depends especially on a divided Congress’s ability to reach a deal. The farm bill expired in late September, when lawmakers were busy fighting over other things, such as how to avoid a state shutdown and who should (or should not) be Speaker of the House. So instead of agreeing on a new bill, they extended the old one by a year.

The expansion temporarily allowed money to flow into programs that support farmers and assist families in need of food. However, it did nothing to tackle climate change or advance anyone’s understanding of how much carbon is in the mush of rotting plants, bacteria, fungi and worm poo under your feet.