To get to the Super Bowl in time, Taylor Swift took a private jet from Tokyo to Los Angeles and then rushed to Las Vegas. The carbon removal company Spiritus estimated that her trip was about 5,500 miles produced about 40 tons of carbon dioxide — about what is generated by charging nearly 5 million mobile phones. But don’t worry, the company assured its critics: It will take those emissions out of the air immediately.

“Spiritus wants to help Taylor and her Swifties”Breathing‘without any CO2’Bad blood,’” it told reporters in a pun-laden pitch. “It’s a touchdown for everybody.”

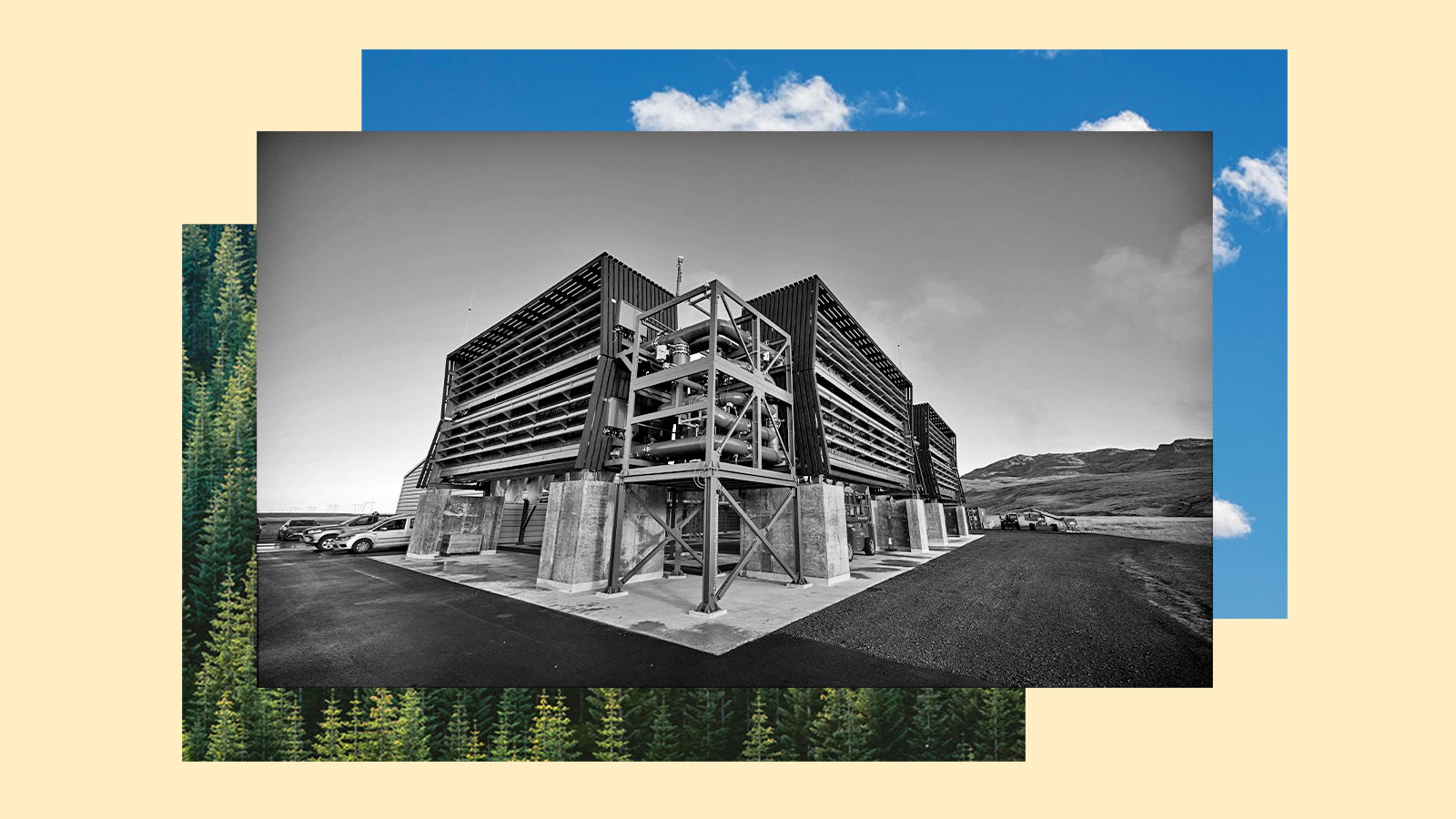

The startup is among dozens, if not hundreds, of companies trying to permanently remove climate-warming gases from the atmosphere. His approach involves extracting carbon directly from the air and burying it, but others sink it into the ocean. Last week, Graphyte, a company backed by Bill Gates, launched to compact sawdust and other woody waste rich in carbon into bricks that it will bury deep under the ground.

Spiritus says “sponsoring carbon offsets is a step toward environmental responsibility, not an endorsement of luxury flights” and added that “celebrities are going to take private jets regardless of what Spiritus does.” Even before the company stepped in, Swift reportedly planned to buy compensation that more than covered her trip. But some climate experts say moves like Spiritus’s illustrate the dangerous direction the fast-growing carbon dioxide removal, or CDR, industry is headed.

“The concern is that carbon removal will be something we do so that business-as-usual can continue,” said Sara Nawaz, director of research at American University’s Institute for Carbon Removal Law and Policy. “We need a very big conversation reframed.”

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says carbon removal will “be required” to meet climate goals, and the United States Department of Energy has a goal of bringing the cost down to $100 per ton (a price point Spirit claims he also wants to deliver). What worries Nawaz is the large role that private companies currently play.

“It’s very market-oriented: doing carbon removals for profit,” Nawaz said. That reliance on the market, she elaborated, will not necessarily lead to the fair, equitable and scalable outcomes she hopes CDR can achieve. “We have to take a step back.”

Nawaz co-authored a report released today titled “Agenda for a Progressive Political Economy of Carbon Removal.” In it, she and her co-authors lay out a vision for carbon removal that moves away from market-centric approaches to those led by government, community and workers.

“What they’re proposing is pretty radical,” said Lauren Gifford, associate director of the Soil Carbon Solutions Center at Colorado State University, who was not involved in the research. She supports the direction the authors are advocating, adding, “They’re actually giving us a road map on how to get there, and that in itself is progressive.”

Nawaz compared carbon removal’s current trajectory to the bumpy road followed by carbon offsets. That industry, in which organizations sell credits to offset greenhouse gas emissions, has been hit misleading claims and perverse incentives. It has also raised concerns about environmental justice where offsets have a disproportionate impact on frontline communities and developing countries. For example, Blue Carbon, a company backed by the United Arab Emirates, was huge plots of land for sale in Africa to fuel its clearing program.

“We don’t want to do that again with carbon removal,” she said.

Philanthropy is one possible alternative to corporate carbon removal. The report mentions a nonprofit organization called Terrace set which makes tax-deductible donations to CDR projects (including Spiritus’). But, says Nawaz, that approach will not grow quickly or sustainably enough to remove the many gigatons of emissions needed to meaningfully address climate change.

“It’s not a scalable approach,” she said. “We’re going to need so much more money.”

The report argues that communities and governments must play a central role in the industry. Nawaz cites community-driven carbon removal efforts in the west, such as the 4 Corners Carbon Coalitionas examples of what is possible at the local level. Nationally she shows up Germany’s transition away from coal as a way for governments to not only fund but fundamentally drive clean energy policy that puts workers at the forefront.

To be sure, the United States is investing in carbon removal. The bipartisan Infrastructure Act and Inflation Reduction Act included billions of dollars for technology such as regional direct air capture hubs. But the legislation mostly positions the government as a funder or buyer of carbon removal initiatives rather than a practitioner.

“It’s honestly a pretty disappointing way it’s developing,” Nawaz said, noting for example that Occidental Petroleum is among those receiving federal funding for carbon removal. She would like to see the government take a more hands-on role. “Not just government procurement of carbon removal. But actually government-led research and early-stage implementation of carbon removal.”

Gifford agrees that there are dangers in the industry relying too much on the private sector. “There’s something really scary about putting the climate crisis in the hands of rich tech founders,” she said. But companies have also been at the forefront of advancing the field. “The climate crisis is one of these all-hands-on-deck things.”

Those in the private sector say their efforts are critical to ensuring carbon removal technology is developed and deployed as quickly as possible. “Our coalition represents innovators,” said Ben Rubin, the executive director of the Carbon Business Council, a nonprofit trade association representing more than 100 carbon management companies. “There won’t necessarily be one silver bullet.”

“There’s a long history of public-private partnerships ushering in some of the world’s latest and greatest innovations,” added Dana Jacobs, chief of staff at the Carbon Removal Alliance, which similarly represents startups in this space. “We think carbon removal will be no different.”

Nawaz and her colleagues want to shake that paradigm before it becomes too deeply entrenched. The alternative may be continued unfair outcomes for marginalized people and limited progress on luxury outlets like Swift’s flight to the Super Bowl.

“The idea is that carbon removal is a public good,” she said. “We don’t have to rely only on the private sector to provide this.”