This coverage is made possible through a partnership with HONEYCOMB and Grista non-profit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future.

In the midst of a difficult year for North Atlantic right whales, a proposed rule to help protect them is a step closer to reality.

Earlier this month, a proposal to expand speed limits for boats – one of the leading causes of death for the endangered whales – took an important step forward: it is now being reviewed by the White House’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, the latest phase of federal review.

Fewer than 360 of the whales remain; only about 70 of them are females of reproductive age. Each individual whale is considered vital to the species’ survival, but since 2017, bowhead whales have experienced what scientists call an Unusual Mortality Event, during which 39 whales died.

Human actions – including climate change – are killing them.

When the cause of a right whale’s death can be determined, it is most often a strike by a boat or entanglement in fishing gear. Three young whales have been found dead this year, two of them with wounds from boat strikes and the third entangled. One of the whales killed by a boat was a calf just a few months old.

Meanwhile, climate change has disrupted their food supply, whale birth rates decrease and pushing them into areas without rules in place to protect them.

“Our impact is now so great that the risk of extinction is very real,” said Jessica Redfern, associate vice president of ocean conservation at the New England Aquarium. “In order to save the species, we must stop our direct anthropogenic impact on the population.”

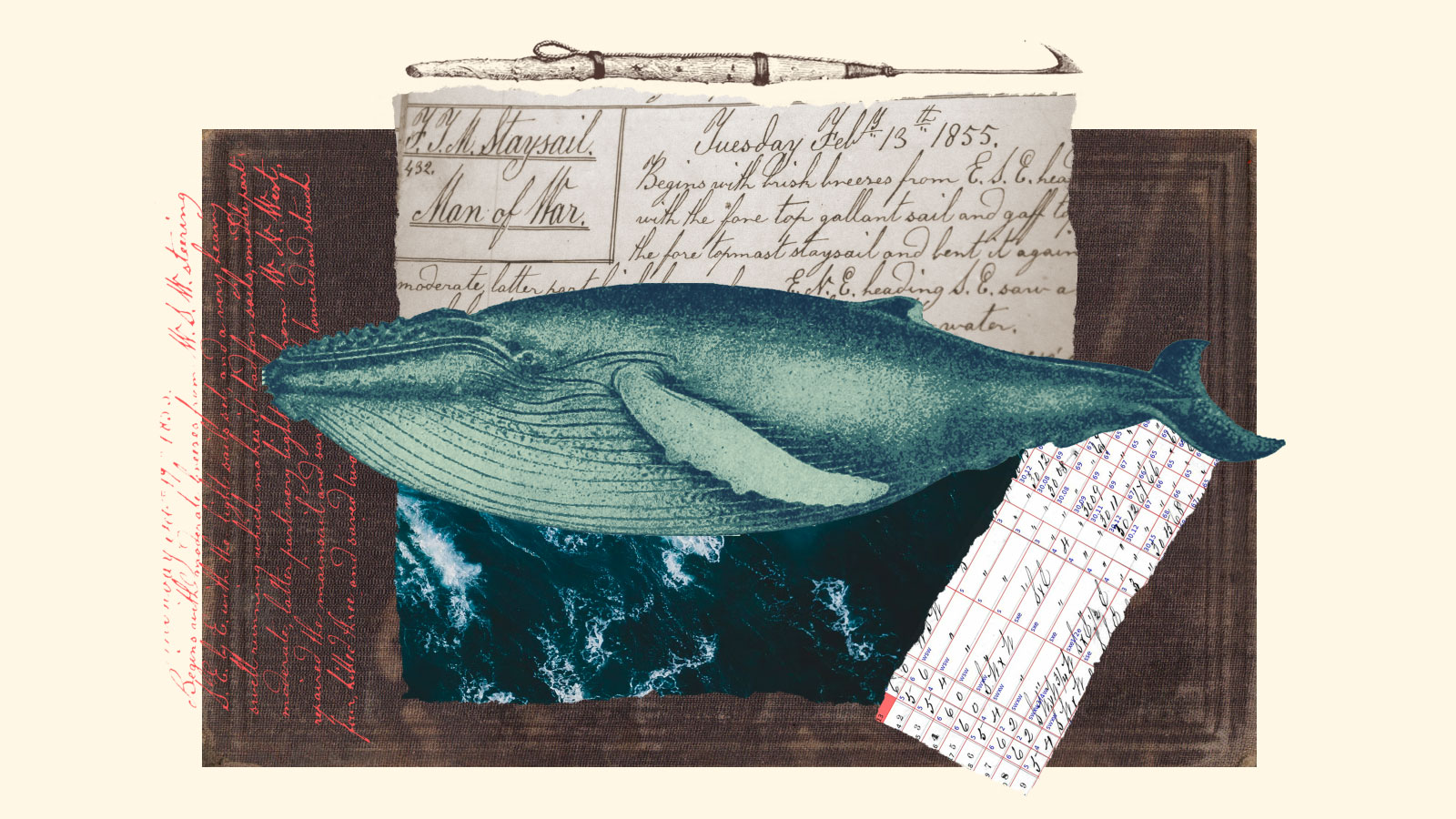

This is not the first time that humans have driven North Atlantic whales to the brink of extinction.

Their name comes from whaling: they were known as the “right whale” to hunt because they spend time relatively close to shorelines, often swimming slowly and close to the surface, and they float when dead. They also yielded large quantities of the oil and whalers were after them. People therefore hunted them to near extinction until it was banned in 1935.

Many of those same characteristics are what make right whales so vulnerable to human dangers today. Because they are often near the surface in the same waters frequented by fishing boats, harbor pilots and shipping vessels, it is easy for boats to collide with them.

“They’ve been called an urban whale,” Redfern said. “They swim in waters that people use; they have high overlap with humans.”

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation / NOAA #24359

To reduce the risk of vessel strikes, ships must travel over 65 feet during designated times of the year when the whales are likely to be in the area. In the Southeast, the speed limits are in force during the winter when the whales calve; outside of New England, the restrictions are in place in the spring and summer when they feed. Regulators can also declare voluntary speed limits in localized places if whales are sighted, known as dynamic management areas.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration proposed in 2022 to expand those restrictions in three ways.

First, the new rule will cover larger geographic areas. The protection zones will stretch along the coast from Massachusetts to Florida at different times of the year, instead of only applying in certain isolated areas.

Second, the change would apply the speed limits to smaller vessels such as fishing boats, rather than just ships over 65 feet.

Third, the new rule will make the speed limits in dynamic management areas – the temporary speed limits where whales have been spotted – mandatory.

Since NOAA published and collected feedback on the proposed rule in 2022, whale advocates have called for the agency to implement it. Those calls have increased in recent months as dead right whales have washed up on beaches.

“There were three deaths, and it was really devastating this year, and two of them were related to vessel strikes,” Redfern said. “It was just emphasized that the absolute urgency, the necessity to get this rule out.”

A leading boating group is speaking out against the expanded speed limits, arguing they could hurt small businesses in the recreational boating industry.

“We are extremely disappointed and upset to see this economically catastrophic and deeply flawed rule proceed to these final stages,” Frank Hugelmeyer, president and CEO of the National Marine Manufacturers Association, said in a statement. “The proposed rule is based on incorrect assumptions and questionable data, and fails to distinguish between large, ocean-going vessels and small recreational boats.”

Right whale scientists have documented in recent years that small recreational boats can injure and kill right whales. At least four of the fatal vessel strikes since the current restrictions began in 2008 have involved boats smaller than 65 feet and therefore not subject to that speed limit, according to Redfern.

NOAA estimated that, based on the size and placement of the propeller wounds, the boat that killed the month-old calf this year was between 35 and 57 feet long — too small to fall under existing speed limits but subject to the new rule if it were to be implemented.

In his statement, Hugelmeyer also pointed to new marine technologies aimed at tracking right whales in the water to reduce vessel strikes without expanding speed limits.

However, scientists like Redfern remain skeptical.

The technology “offers a lot of promise,” she said, but the speed limits have been proven.

“It’s really important, I think, that we rigorously evaluate the technology that’s being proposed to make sure that it’s going to achieve the same type of risk reduction that we’re seeing with the slowdowns in extended areas,” she said.

Many groups have since expressed concern that offshore wind turbines could harm whales. There is no evidence of thataccording to NOAA.