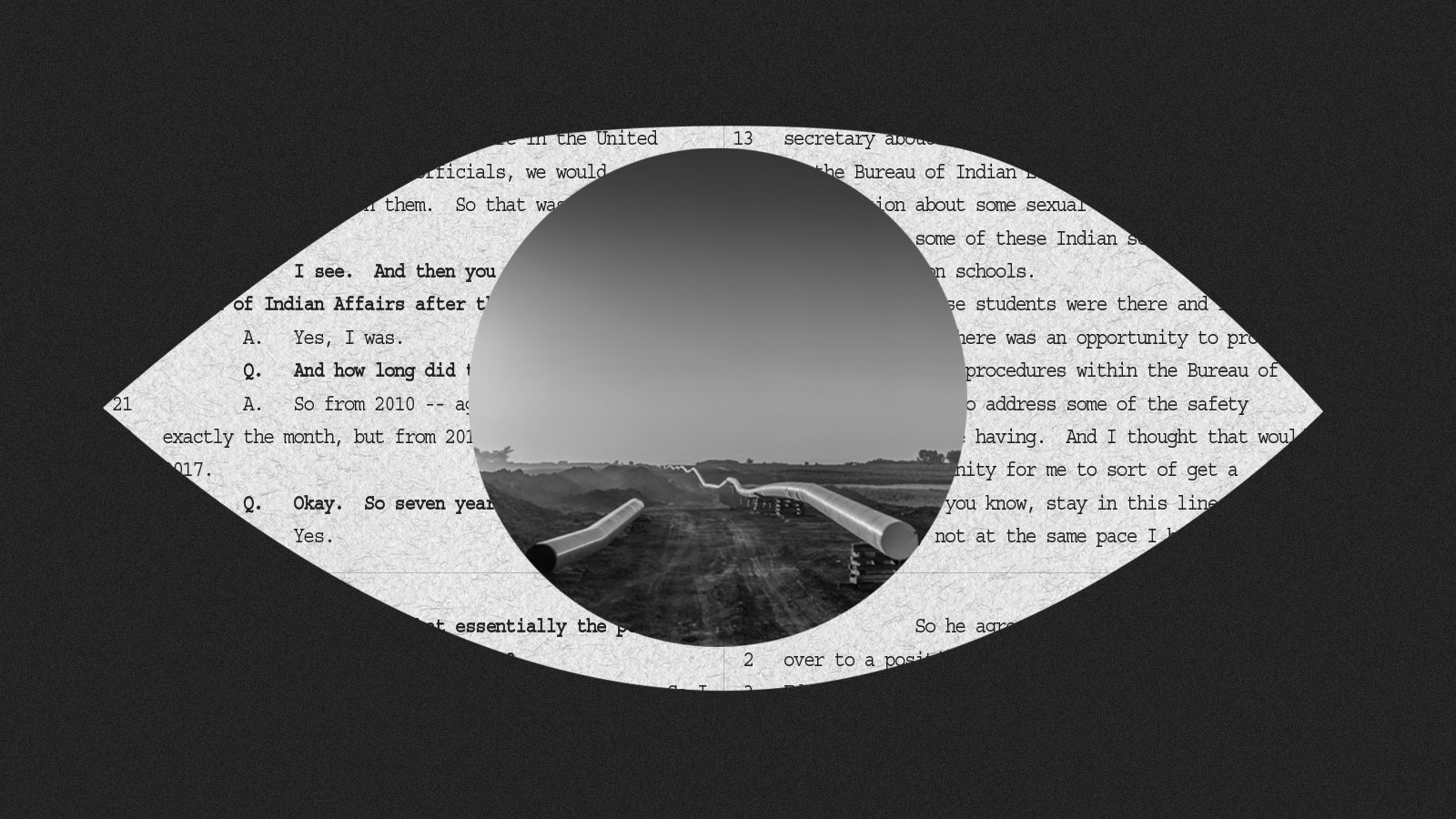

Up to 10 FBI-run informants were embedded in anti-pipeline resistance camps near the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation at the height of mass protests against the Dakota Access pipeline in 2016. The new details about federal law enforcement surveillance of an indigenous environmental movement have been released as part of a legal battle between North Dakota and the federal government over who should pay for policing the pipeline fight. So far, the existence of only one other federal informant in the camps has been confirmed.

The FBI also routinely sent plainclothes agents into the camps, one former agent told Grist in an interview. Meanwhile, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA, operated undercover narcotics officers out of the reservation’s Prairie Knights Casino, where many pipeline opponents rented rooms, according to one of the statements.

The operations were part of a broader surveillance strategy that included drones, social media monitoring and radio tapping by a variety of state, local and federal agencies, according to lawyers’ interviews with law enforcement. The FBI infiltration fits into a longer history in the region. In the 1970s, the FBI infiltrated the highest levels of the American Indian Movement, or AIM.

The indigenous-led uprising against Energy Transfer Partners’ Dakota Access oil pipeline drew thousands of people seeking to protect water, the climate and indigenous sovereignty. The participants protested for seven months to stop construction of the pipeline and were met by militarized law enforcement, sometimes facing tear gas, rubber bullets and water hoses in sub-freezing weather.

After the pipeline was completed and protesters left, North Dakota sued the federal government for more than $38 million — the cost the state claims it spent on police and other emergency responders, and for property and environmental damage. Central to North Dakota’s complaints is the existence of anti-pipeline camps on federal land run by the Army Corps of Engineers. The state argues that by failing to enforce trespass laws on that land, the Army Corps allowed the camps to grow to 8,000 people and serve as a “safe haven” for those who engaged in illegal activities during protests and damaged property.

In an effort to prove that the federal government has failed to provide adequate support, lawyers have deposed officials leading several law enforcement agencies during the protests. The depositions provide unusually detailed information about the way federal security agencies are intervening in climate and indigenous movements.

Until the lawsuit, the existence of only one federal informant in the camps was known: Heath Harmon was working as an FBI informant when he entered into a romantic relationship with water protector Red Fawn Fallis. Finally a judge Fallis sentenced to almost five years in jail after a gun went off when she was tackled by the police during a protest. The gun belonged to Harmon.

Manape LaMere, a member of the Bdewakantowan Isanti and Ihanktowan groups, who is also Winnebago Ho-chunk and spent months in the camps, said he and others expected the presence of FBI agents because of the agency’s history . Camp security kicked out several suspected infiltrators. “We were already cynical because our hearts had been broken by our own family members before,” he explained.

“The culture of paranoia and fear created around informants and infiltration is so detrimental to social movements because these movements for indigenous people are typically based on kinship networks and forms of relationality,” says Nick Estes, a historian and member of the Lower Roaring Sioux. Tribe who spent time at the Standing Rock resistance camps and extensively investigated the infiltration of the AIM movement by the FBI. Beyond his relationship with Fallis, Harmon had close family ties to community leaders and participated in important ceremonies. Infiltration, Estes said, “turns family members against family members.”

Less well known than the FBI’s covert operations are those of the BIA, which serves as the primary police force on Standing Rock and other reservations. During the NoDAPL movement, the BIA had “a few” narcotics officers operating undercover at the Prairie Knights Casino, according to the statement of Darren Cruzan, a member of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma who was then the director of the BIA’s Office of Justice Services were .

It is not unusual for the BIA to use secret officers in his drug busts. However, the information gathered by the Standing Rock divers went beyond drugs. “It was part of our effort to gather information about, you know, what happened within the boundaries of the reservation and whether there were any plans to move camps or add camps or those kinds of things,” Cruzan said .

A spokesman for Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who oversees the BIA, also declined to comment.

According to the statement of Jacob O’Connell, the FBI’s supervisor for the western half of North Dakota during the Standing Rock protests, the FBI infiltrated the NoDAPL movement weeks before the protests gained international media attention and drew thousands . By August 16, 2016, the FBI had assigned at least one “confidential human source” to gather information. The FBI ended up having five to 10 informants in the protest camps — “probably closer to 10,” Bob Perry, assistant special agent in charge of the FBI’s Minneapolis field office, which oversees operations in the Dakotas, said in another deposition said. The number of FBI informants at Standing Rock was first reported by the North Dakota Monitor.

According to Perry, FBI agents told recruits what to collect and what not to collect, saying, “We don’t want to know about constitutionally protected activities.” Perry added, “We’ll essentially give them a list: ‘Violence, potential violence, criminal activity.’ Up to a point it was also health and safety because, you know, we put an informant and had them in a position where they could report on it.”

The statement from US Marshal Paul Ward said that the FBI also sent agents undercover into the camps. O’Connell denied the claim. “No secret agents were used whatsoever.” However, he confirmed that he and other agents did visit the camps regularly. For the first few months of the protests, O’Connell himself arrived at the camps shortly after dawn most days, wearing outerwear from REI or Dick’s Sporting Goods. “Being in civilian clothes, we were able to kind of hang around and, you know, do what we needed to do,” he said. O’Connell would chat with whoever he came across. Although he sometimes handed out his card, he did not always identify himself as FBI. “If people didn’t ask, I didn’t tell them,” he said.

He said two of the agents he worked with avoided confrontations with protesters, and Ward’s statement indicated the couple raised concerns with the US officer about the safety of entering the camps without the local police knew about it. Despite its efforts, the FBI has discovered no widespread criminal activity beyond personal drug use and “criminal-type activity,” O’Connell said in his statement.

The US Marshals Service, as well as Ward, declined to comment, citing ongoing litigation. An FBI spokesman said the press office does not comment on litigation.

Infiltration was not the only activity conducted by federal law enforcement. Customs and Border Protection responded to the protests with its MQ-9 Reaper drone, a model best known for remote airstrikes in Iraq and Afghanistan, which flew above the camps by August 22, providing video footage known as the “Bigpipe Feed .” The drone flew nearly 281 hours over six months, costing the agency $1.5 million. Customs and Border Protection declined a request for comment, citing the litigation.

The biggest beneficiary of federal law enforcement spending was Energy Transfer Partners. In fact, the company donated $15 million to North Dakota to help foot the bill for the state’s parallel efforts to stem the disruptions. During the protests, the company’s private security contractor, TigerSwan, coordinated with local law enforcement and passed on information gathered by his own under cover and eavesdrop operations.

Energy Transfer Partners also tried to influence the FBI. However, it was the FBI that began its relationship with the company. In his statement, O’Connell said he arrived at Energy Transfer Partners’ office within a day or two of starting to investigate the move and soon met and communicated with executive vice president Joey Mahmoud.

At one point, Mahmoud pointed the FBI to the indigenous activist and actor Dallas Goldtoothand said that “he is the ring leader who makes it violent,” according to an email that described an attorney.

During the protests, federal law enforcement officials pushed for more resources to police the anti-pipeline movement. Perry wanted drones that could zoom in on faces and license plates, and O’Connell thought the FBI should investigate crowd-sourced funding that could have ties to North Korea, he claimed in his statement. Both requests were denied.

O’Connell explained that he was more concerned about China or Russia than North Korea, and it wasn’t just state actors that worried him. “If someone like George Soros or some of these other well-heeled activists try to disrupt things in my field, I want to know what’s going on,” he explained, referring to the billionaire philanthropist, who conspirators theorize control progressive causes.

For the federal law enforcement officers working on the ground at Standing Rock, there was no reason they couldn’t use all the resources at the federal government’s disposal to confront this latest indigenous uprising.

“That shit should have been crushed like immediately,” O’Connell said.