The spotlight

When Grist writer Tik Root set out on a journey to degas his home, he initially had no intention of documenting the effort. As a journalist covering climate, he has years of experience reporting on electrification, energy and technology – and demystifying those often complex topics for the average consumer. But the decision to write about his own experiences as a homeowner trying to ditch fossil fuels came about two-thirds of the way through what amounted to more than a year-long process.

“I said, ‘OK, if I spend all my days doing this and I learn so much, maybe other people will learn something,'” he recalls.

Residential energy consumption accounts for about one sixth of total greenhouse gas emissions in the US Our homes remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels, and especially natural gas. But that’s starting to change – electric heat pump sales is more than gas boilers, and some cities have passed resolutions banning the use of natural gas in new construction. Law such as the Inflation Reduction Act also sought to make it cheaper and more accessible for Americans to upgrade their home energy systems and appliances to more efficient ones.

Still, that doesn’t mean it’s easy or cheap to renovate a home to be more climate-friendly, as Tik and his wife discovered. Even a few climate journalists encountered obstacles and difficult decisions in the course of a process that took several times longer than they initially expected.

“Build on time,” advises Tik to anyone thinking about similar upgrades. “It’s going to take longer than you think.”

He recorded his and his wife’s experiences in a first-person feature for Grist, which was published today—and he shared some of his best takeaways for Looking Forward. In addition to budgeting more time than you think you’ll need, Tik recommended leaning on family and friends who were early adopters of things like heat pumps, induction stoves, and solar panels.

“It’s only a matter of time — if not already — before someone on your block has a heat pump, and if you ask them about their process, you can probably skip a whole bunch of steps,” he said. Shortly after he and his wife installed heat pumps at their two-story home in Burlington, Vermont, a neighbor who noticed the contractor’s truck in their driveway called to ask about it and see if she could hire the same installer. “I think my neighbor probably saved three months of work,” Tik said. “And my friend is just about to do the same; my father will do the same.”

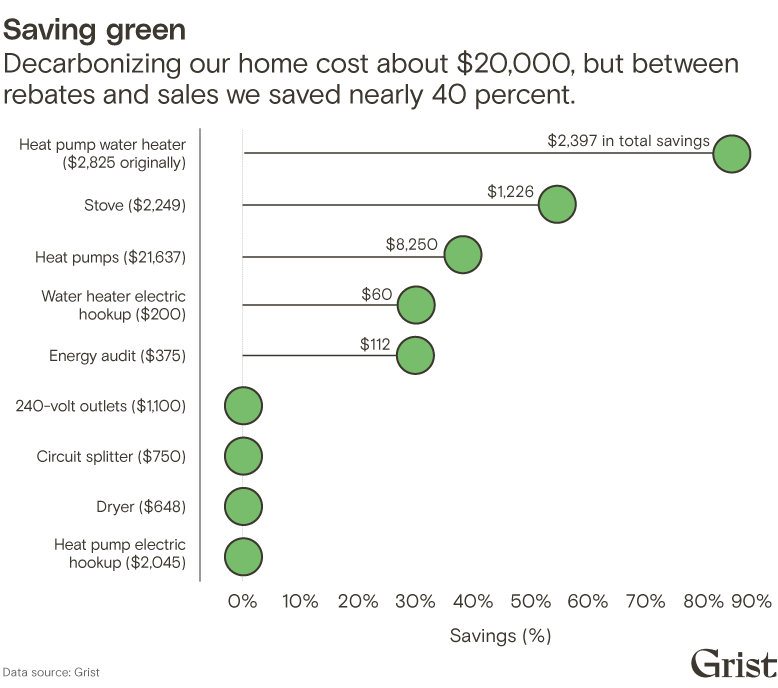

A home’s heating system is the big ticket item in terms of financial investment and emission saving potential. For Tik and his wife, the journey leading to installation involved comparing different models of heat pumps, a long detour exploring rooftop solar (to offset some of the energy needs and costs of their new all-electric systems) , and a brief moment of panic when they feared they needed to upgrade their electrical panel. They worked through each of these decisions one by one, culminating in a successful – even joyful – installation in early January.

The heat pump setup that Tik and his wife chose is a “mini split” system. It consists of three condensers (one for each floor), installed outside, and ductwork in the attic to reach the upstairs bedrooms. Philip Martin

We’ve excerpted Tik’s feature below (lightly edited for clarity), highlighting some of the other lower-lift projects he and his wife have taken on to start weaning the full house off natural gas. Check out the full feature, with all its twists, here.

– Claire Elise Thompson

![]()

Our first attempt at ditching gas was installing a heat pump water heater. It works a bit like an air conditioner in reverse draws warmth from the surrounding air bringing water to temperature, and the technology is growing in popularity. Not only are heat pumps energy efficient, they can also do some dehumidification, which our musty basement badly needed. The process was deceptively smooth.

We have collected several quotes – something that the [director of research for the electrification nonprofit Rewiring America] and others have told me that managing costs is critical. The lowest was $2,825 to install a 50-gallon tank, a price that on the high end of Energy Star guidance but hundreds less than the others. A $600 immediate rebate from the state and an $800 post-purchase one from the city brought the cost to $1,425. I happened to have a friend who also needed one, so we both got another $150 off for doing it together. The IRA offers a tax credit of 30 percent of the total cost (up to $2,000), although we won’t get it until after we file our taxes.

All told, the bill will come to $428, plus a few hundred more to have an electrician. Installation took less than a day and the water heater is now humming happily in our basement. Although the emissions savings will be negligible because we still need our boiler for space heating, it was a confident first step in reducing our dependence on gas.

Buoyed by the success, we aimed for the stove and the dryer.

![]()

Electrification of appliances is not yet a major climate victory. The average dryer used approximately 2,000 cubic feet of natural gas per year, with CO2 emissions roughly equivalent to driving around 300 miles. Gas stoves consume about the same amount. At best, electric fully displaces those greenhouse gases. But the benefits are even smaller than in Vermont, where local utilities aren’t as clean. The nation continues to generate 60 percent of its electricity with fossil fuels (43 percent of it from natural gas) and until that changes, it’s trashing a gas stove more or less a wash for the planet.

Our main motivation for throwing out gas equipment was the flashing light on our air purifier. We read the research that shows that boiling over gas production benzene and nitrogen dioxide. But seeing that little diode change from a soft blue to a bright red every time we cooked was a looming reminder of the risks. It became even more disturbing when we found out we were going to be parents, since gas stoves are connected to almost 13 percent of the nation’s childhood asthma cases.

The consensus among climate experts and, perhaps just as importantly, chefs is that the best alternative is an induction stove, which uses electromagnetic energy to heat cookware. It requires less energy than a traditional electric range and offers greater temperature control. But when we started exploring options, we quickly realized the technology wasn’t cheap. The cheapest models start at about $1,100, or almost twice the price of a basic gas stove. Proponents of the technology say prices should come down as it becomes more widespread, but that didn’t do us much good, and our city’s rebate was only $200. We hoped Black Friday would further blunt the financial blow, although that meant waiting a few months. We used the time to weigh whether we wanted features like a convection oven (we did) and went to Lowe’s in November.

Given my propensity for buying power tools I don’t need, my wife drove me straight to the appliances. Alas, the store only had one induction model on display, and it wasn’t the one we wanted. But the conventional stoves were similar enough that we could get an idea of how the induction version might feel in the kitchen. After much pushing, turning, hemming and chasing, we chose a Samsung induction model with knobs rather than buttons, which we knew from a family member’s experience could be finicky. The list price was $2,249, but we got it for almost half off in the holiday sale.

On our way out, we solved our dryer dilemma when we came across a well-reviewed electric model similarly marked down to just $648. We pulled out our phones and compared it to a heat pump dryer, which would have used less electricity and saved us the trouble of installing another outlet and vent. But aside from being significantly more expensive (even with an extra government discount), the heat pump version only had half the capacity. Given the mountains of laundry that newborns produce, we chose the traditional technology, hoping that larger models are available next time we need a dryer.

When I left the store, I almost blew our savings on a track saw. Good job, I showed restraint as installing outlets to power our purchases was much more expensive than expected. The electrician charged over $600 for the stove hookup, and the dryer vent, when our basement remodel is ready to accommodate it, will probably work about the same. Although it’s about two-thirds the cost of appliances, we saw the benefits of gassing almost immediately.

My wife does most of the cooking and faints when she turns on an induction burner. Water boils much faster than with the gas stove and even faster than in our electric kettle. “It feels almost immediate,” she said. “The bubbles are crazy.” The heat is also just right enough to simmer pasta sauce and keep food perfectly warm while we assemble our dinner plates.

Best of all, it’s been months since we saw the red light on our air purifier.

![]()

CORRECTION: In last week’s newsletter, about alternatives to synthetic substancesfailed to take note of the textile recycling company Renewcell filed for bankruptcy last month. The next steps for the company, its patented technology and its inventory of recycled materials are uncertain.

More exposure

A parting shot

Although Tik and his wife eventually decided to put solar panels on their roof, they are now looking into it community solar power – an arrangement that allows neighbors to buy a larger solar installment at a centralized location, such as a school or a church. Here is such a project on Crystal Spring Farm in Brunswick, Maine. The panels are jointly owned, and they provide energy to the farm as well as several nearby families who would otherwise not have individual access to solar power.