Every email you send has a home. Every uploaded file, web search, and social media post does, too. In massive buildings erected from miles of concrete, stacked servers hum with the electricity needed to process and store every morsel of information modern lives rely on.

In recent years, these data centers have expanded rapidly in the United States. But the giant facilities do more than keep cloud servers running—they also siphon absurd amounts of water to run cooling systems that protect their components from overheating. Now, as artificial intelligence applications become ubiquitous, they use more water than ever.

Northern Virginia is the data center capital of the world, where more than 300 facilities process nearly 70 percent of the world’s digital information, a job that requires more and more electricity. A utility serving the area, Dominion Energy, announced during an earnings call on May 2 that the industry’s demand for electricity has more than doubled in the past year. The week before that call, Google announced a billion dollars expansion of three Virginia facilities, following a $35 billion investment by Amazon Web Services in the same area last year. State lawmakers and environmental groups have begun to worry about what this boom in the industry means for the area’s water supply.

“Some of these data centers will use resources equivalent to a small city for energy and water,” said Ann Bennett, chair of data center issues in the Sierra Club’s Virginia chapter. “They’re being built on a scale that we just haven’t seen in the past.”

Large data centers are resource pigsusing as much as 5 million liters of water per day. Big companies, such as Google, Microsoft and Meta, faced public backlash for pumping up groundwater in drought-stricken regions, such as in Arizona. But warm temperatures and more heat waves driving increased water scarcity even in states unaccustomed to shortages. Last summer and fall, Virginia suffered for months drought. The worst of the drought was in the same watershed as “data center alley,” part of Loudoun County where thousands of tech companies make use the greatest concentration of data centers in the world, in area the size of 100,000 football fields.

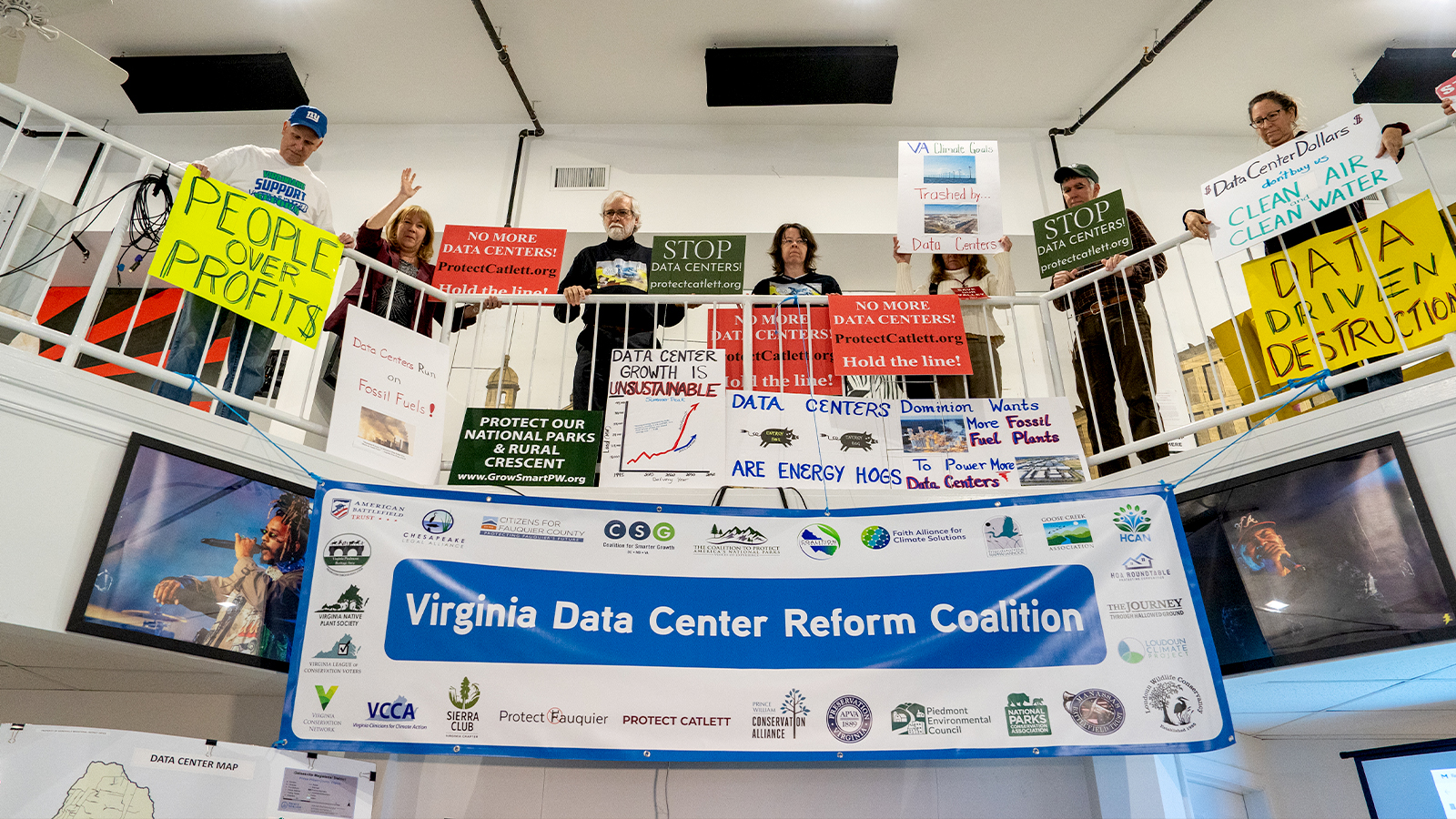

“I think as we look at climate change and drought, somebody needs to start asking these questions about how that affects water supply and future increased need,” said Kyle Hart, a program manager for the National Parks Conservation Association in Alexandria, one of the groups involved in the recently formed Virginia Data Center Reform Coalition. Many environmental advocates say that because companies often do not disclose details about their water use, it is a challenge to draw attention to these issues.

Jahi Chikwendiu / The Washington Post via Getty Images

Data centers are among the top 10 water consuming industries in the United States, according to a 2021 study from Virginia Tech that looked at their environmental costs. And the next generation of technology will only make these facilities thirstier, as servers using AI algorithms generate more heat. Compared to traditional computer, the average neural network needs six times more kilowatts per rack. And AI scales exponentially: Large-scale algorithms, used by the likes of Google, Amazon and Microsoft, consume at least 100 times more computing power and process millions more data points than simpler types of machine learning.

Cracking all those grips are tech giants looking for more data centers. Information on how many servers are used for AI applications is not publicly available, but according to polling by Forbes, more than half of businesses use AI in some capacity. Amazon Web Services, which has 85 data centers in northern Virginia alone, offers hundreds of AI applications to his customers.

In Virginia, some residents are concerned about the scramble to put land up for grabs for data centers. In December, local officials in Prince William County approved a $40 billion land development project that will turn the county into the world’s largest data center hub. The public debate took 27 hours and drew nearly 400 citizens who raised questions about water availability, effect on the network and noise pollution.

Dozens of climate advocacy and historic preservation organizations formed the Virginia Data Center Reform Coalition late last year over concerns that data centers are being built without first understanding the consequences. Julie Bolthouse, director of land use at Piedmont Environmental Council, one of the members of the coalition, says without more information about the resources these facilities consume, it’s hard to draw a line from data centers to water issues. “We just don’t know. And this is the biggest problem: We need more transparency around this industry,” she said. “And yet we approve of them because of the promise of increased revenue.”

“Data centers are really secretive about their operational details,” said Md Abu Bakar Siddik, an engineering doctoral student who co-authored the Virginia Tech study. In 2022, Google became the first company to release its water usage data in The Dalles, Oregon. after a long legal battle. While a handful of other tech giants, such as Microsoft, have followed suit, most companies remain tight-lipped.

Ben Townsend, head of infrastructure and sustainability at Google, says the tech giant has some of the most sustainable data centers in the industry. And if a drought hits the area, Townsend said Google will work with local utilities “ahead of time to understand what behaviors need to be taken to best support the watershed.”

Last month, Bolthouse learned from a Freedom of Information Act request that data centers served by the Loudoun water utility increased their use of potable water by more than 250 percent between 2019 and 2023. The documents also showed that water consumption peaked during the summer months. when the risk of drought is highest.

Recycled water is used at some data centers, such as a Google facility Colorado. But Siddik says fresh water is usually needed to keep cooling systems running smoothly.

Hugh Kenny / Piedmont Environmental Council

Shaolei Ren, an engineering professor at the University of California, Riverside, said that instead of returning the water to a city wastewater system, like the one connected to your drains at home, many data centers use cooling methods that rely on evaporation. A study last year he co-authored a finding that just training Open AI’s flagship product, GPT-3, may have directly evaporated more than 700,000 gallons of clean fresh water. “Whether the water is recycled, salt water or fresh water, after that the water is just gone,” Ren said.

Some Virginia lawmakers have sought to hold companies accountable for their impact on the environment. In February, Josh Thomas, a Democrat in the Virginia House of Representatives, introduced several data center reform bills, including one that would require counties to conduct water studies before approving new developments. Although the legislation made it through the Virginia House in February, the Senate vote was finally postponed until 2025, effectively killing it. According to Thomas, industry groups opposed the bill. By the time he reintroduces it during next year’s legislative session, lawmakers and the Data Center Reform Coalition expect an environmental impact studycommissioned by Virginia, will be completed.

“I think it’s very fair to paint a picture of a very stubborn industry that is opposed to any type of control on its growth,” Thomas said. “If we don’t do something quickly, there could be a tipping point where anything we do can’t have an impact.”