More than any other fossil fuel company, Occidental Petroleum – known as Oxy – has built its climate strategy around innovations that capture carbon before it can be released or pull it directly from the air. The Texas-based oil giant, which made more than $23 billion in revenue last year, says on its website that this “visionary technologies” will help it achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions and enable a lower-carbon future.

Scientists agree that such technologies will be needed to limit global warming. But Oxy’s plans for them appear to be less about sustainability and more about creating a “license to pollute,” according to a new analysis from the nonprofit Carbon Market Watch. The analysis describes Oxy’s focus on carbon capture and removal as an “expensive fig leaf for business as usual,” allowing the company to claim emissions reductions while continuing to profit from the sale of fossil fuels — rebranded as “net -zero oil” and “sustainable aviation fuels.”

The company “makes this whole spiel about meeting the Paris Agreement’s goals, but it very clearly flies in the face of it,” said Marlène Ramón Hernández, a carbon removal expert at Carbon Market Watch and a co-author of the report. “What we need to do is phase out fossil fuels, not continue their life.”

Oxy first laid out its side net zero strategy in 2020, making it the first US oil major to do so. Today, Oxy outlines that strategy use four R’s: The company says it will “reduce” operational emissions, “revolutionize” carbon management, “remove” carbon from the atmosphere and “reuse/recycle” it to produce new low-carbon or zero-emissions products. Its overarching goal is to achieve net-zero emissions for its operations and indirect energy use by 2040.

This is where the problems begin, according to Carbon Market Watch. Despite Oxy’s net-zero pledge for its operation and energy use, it is much more vague about the emissions associated with the oil and gas it sells. These emissions, known as Scope 3 emissions, represent more than 90 percent of Oxy’s greenhouse gas footprint in 2022. The company has claimed an “ambition” to eliminate them by 2050.

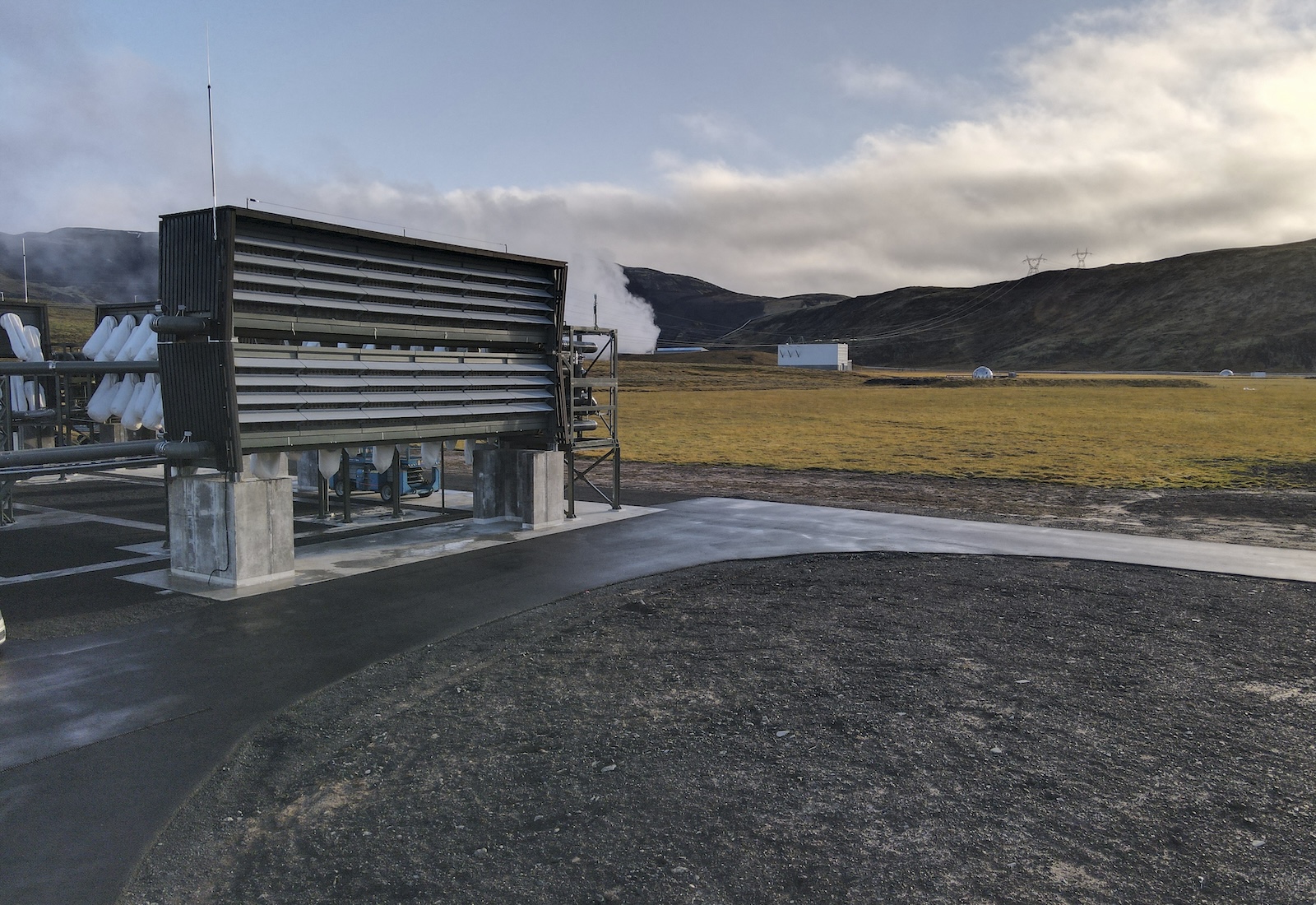

However, Oxy does not plan to reduce Scope 3 emissions by phasing out the production of oil and gas, but through investments in carbon removal. Direct air capture, or DAC — a technology that uses large fans and chemical reactions to separate carbon dioxide from the air — is a main focus. An Oxy subsidiary called Oxy Low Carbon Ventures announced in 2022 that it would deploy up to 135 DAC plants by 2035and last year Oxy bought a major DAC technology company for $1.1 billion.

Halldor Kolbeins / AFP via Getty Images

Some of Oxy’s DAC projects are already in the pipeline. The largest, called Stratos, is under construction in the Permian Basin, a massive oil field, in Texas. If it reaches its nameplate capacity of capturing half a million metric tons of carbon dioxide a year — which Oxy says it will do by mid-2025 — it will be 14 times larger than the largest DAC facility in the world. (That facility, owned by the Swiss company Climeworks, started working in Iceland this week with a nominal capacity of 36,000 metric tons of CO2 per year.)

However, for DAC to result in net removal of carbon dioxide, captured carbon must be kept out of the atmosphere forever. This is usually achieved by enclosing them in rock formations. However, Oxy CEO Vicki Hollub said it would be a “waste of a valuable product,” and plans to use the captured carbon instead. In one application, these would be converted into synthetic electrofuels — low-carbon fuels made from their chemical constituents using electricity — and sold to other companies.

The other major application is for a process known as enhanced oil recovery, where CO2 is injected into oil and gas wells to extract hard-to-reach reserves of fossil fuels. This forms the basis for Oxy’s “net-zero oil” claims. According to the company’s logic, the atmospheric carbon dioxide injected into the ground cancels out any new emissions from the oil and gas it is used to draw up. In a interview with NPR last DecemberHollub said this approach means that “there is no reason not to produce oil and gas forever.”

Before that, at a conference last March, Hollub told audience members that DAC would be “the technology that helps preserve our industry over time,” extending his social license to operate for “60, 70, 80 years.”

Neither Carbon Market Watch nor the independent experts Grist spoke with look favorably on these approaches. Charles Harvey, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at MIT who was not involved in the report, called it “absurd” to use captured carbon to make so-called sustainable aviation fuels; these fuels will eventually be burned, releasing the trapped carbon back into the atmosphere.

In fact, the whole process can result in a net Increase in greenhouse gas emissions, as DAC is an energy-intensive process often fueled by fossil fuels. Oxy has no publicly announced plans to power its carbon capture and removal facilities with renewable energy. “They will release more CO2 than they capture,” Harvey said.

As for “net-zero oil,” Carbon Market Watch calls it an “oxymoron and a logical fallacy.” A 2021 analysis by the US Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory suggests that this application would also result in net-positive emissions – both because it requires so much energy (probably provided by fossil fuels) just to run a DAC plant, and because every metric ton of carbon dioxide injected into oil fields, two to three barrels of oil. Each barrel of oil generates half a metric ton of carbon dioxide when burned, meaning that every metric ton of carbon dioxide used for Oxy’s net-zero oil can cause 1 to 1.5 tons of CO2 emissions.

Brandon Bell/Getty Images

Hernández said she is also concerned about Oxy’s plans to generate carbon credits from its DAC projects. Although none of its planned DAC facilities have yet been built, Oxy has already pre-sold or is in negotiations to sell DAC-generated carbon credits representing between 1.63 million and 1.98 metric tons of carbon dioxide, according to Carbon Market Watch’s calculations . If the company uses the same captured carbon to offset its own emissions and generate credits, which can be used to offset the emissions of another company “It’s a blatant issue of double counting,” Hernandez told Grist.

Oxy did not respond to Grist’s request for comment.

Holly Jean Buck, an assistant professor of environment and sustainability at the University at Buffalo, said it is possible to pursue DAC responsibly. Even a moonshot project like Stratos can be seen as having significant demonstration or research value. “The point is to find out if the technology is going to work at a real level,” she told Grist.

That said, she agreed there are ways Oxy can make its DAC agenda more credible. “They could make a commitment to build renewable power to power it,” she offered, or donate the technology to developing countries.

Buck and some other academics say fossil fuel companies should be doing more of this research — or at least paid the bill for it – in order to accept responsibility for their role in the climate crisis. However, Harvey argues that there is a opportunity cost to such research and deployment, which is expensive. He and other researchers estimated that it would cost Oxy’s Stratos facility $500 to capture each metric ton of carbon dioxide. (The company predicts that costs will drop to approx $200 per ton by 2030.)

Every dollar spent on DAC means a dollar not spent on more reliable, immediate emissions reductions. “There’s low-hanging fruit to do before you get there,” he said, such as building renewables for non-DAC purposes, insulating homes, installing heat pumps or putting more batteries on the grid with existing renewables .

“Almost anything is better” than DAC, Harvey said.

As a necessary first step toward a more credible net-zero strategy, Hernández suggested that Oxy abandon its aggressive plans to extract more oil and gas, as they are not in line with scientists’ call for a dramatic cut in production to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). “He’s actually planning to increase his oil production, so there’s clearly no intention to go to net zero,” she said.