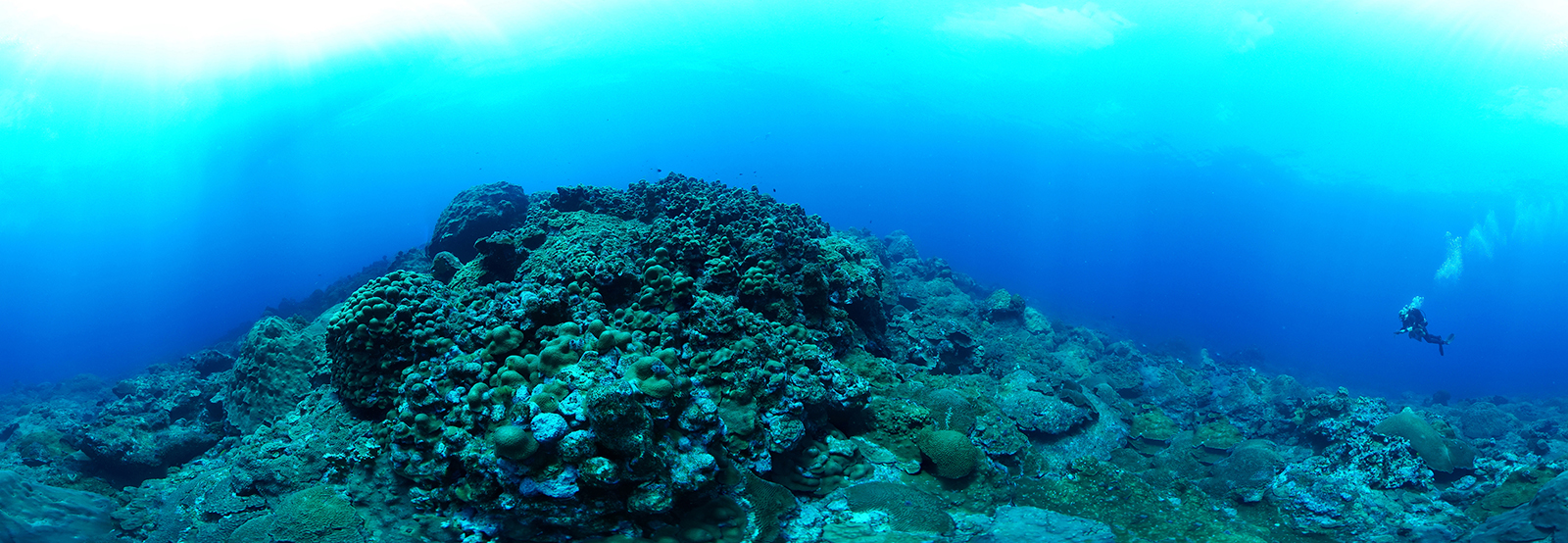

While the Gulf of Mexico is a region known for oil, it is also home to something much less expected. Nestled among offshore oil platforms, about 150 miles from Houston, is one of the healthiest coral reefs in the world: the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary.

Marine researchers who have visited the Flower Garden Banks describe it with awe in their voices. “When you look out, it can be almost disorienting because there’s so much coral,” said Michelle Johnston, superintendent of the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary.

As reefs around the world bleach at an alarming rate, scientists are racing to study and preserve this remarkable coral reef in the most unlikely of places. “We have these magical underwater places, [and yet they are] completely surrounded by the oil and gas industry,” Johnston said.

Emma Hickerson / Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary via NOAA

Understanding how both can exist so close together helps to understand the history of the region. About 190 million years ago, the sea here was drying up, leaving behind a massive salt flat. Over the centuries, that dried layer of salt has been buried deep in the earth.

And eventually a new body of water—the Gulf of Mexico—formed high above it. Because salt is less dense than the surrounding rock, the layer slowly rose to the surface, pushing the earth above it, while massive deposits of oil were pulled up from below. Slowly, this shift created enormous underwater mountains known as “salt domes”. If you look at a map of the Gulf of Mexico today, you can see that many of its oil rigs are on the same underwater mountains.

A few of these mountains rose so high that sunlight could only filter through the water to reach them. And about 10,000 years ago, coral polyps attached to the peaks and began to grow. Those submerged mountain tops are now the Flower Garden Banks.

Because the reef is so far from the coast, it is protected from many threats such as overfishing and coastal pollution. And because of its depth and northern latitude, the water here is about as cold as corals can tolerate, essentially protecting the Flower Garden Banks from global warming. In the summer of 2023, for example, while other reefs across the Caribbean were plagued by heat stress and bleaching, the unique geology of Flower Gardens allowed it to outperform the rest.

But the same unique geology has also turned the region into a massive hub for offshore oil drilling.

“When you dive in the ocean at the Flower Gardens, you look around from the submarine and you can see oil and gas platforms in every direction,” Johnston said. “So there’s all this industry happening around this beautiful place.”

LM Otero/AP Photo

For now, the reef has thankfully avoided any catastrophic oil spills, but that doesn’t mean oil hasn’t left its mark. In fact, the legacy of oil extraction, carbon emissions and climate change is literally etched into the hard skeletons of the corals themselves.

“I think of that skeletal material as a little time capsule,” said Amy Wagner, a scientist who studies corals for clues about Earth’s past.

When she was a graduate student in 2005, Wagner and a team of scientists came to Flower Garden Banks in search of one very specific type of coral, Siderastrea siderea. “They just look like a bunch of rocks on the bottom,” she said.

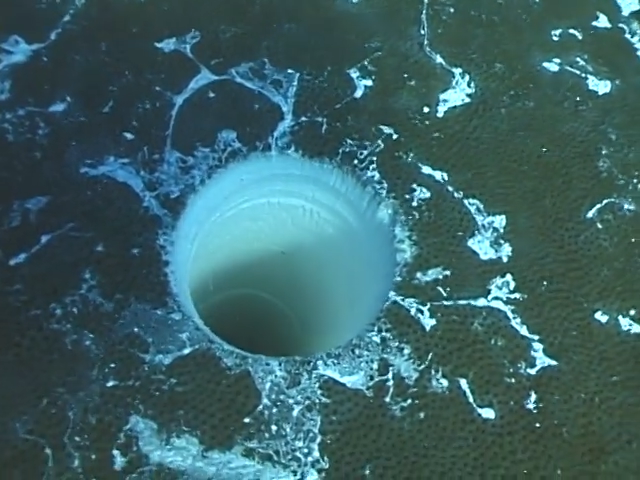

The team descended 78 feet, to the peaks of these ancient mountaintops, and drilled a nearly 6-foot-long core of this slow-growing species of coral—a 250-year record of pollution, climate change, and even global events. “You start drilling in and, especially in that initial drilling, you get the tissue layer of the coral,” Wagner said. “And you end up letting a lot of fish in because it’s free food, right?”

Amy Wagner’s team drills a coral sample from the Flower Garden Banks in 2005. Courtesy of Amy Wagner and John Halas

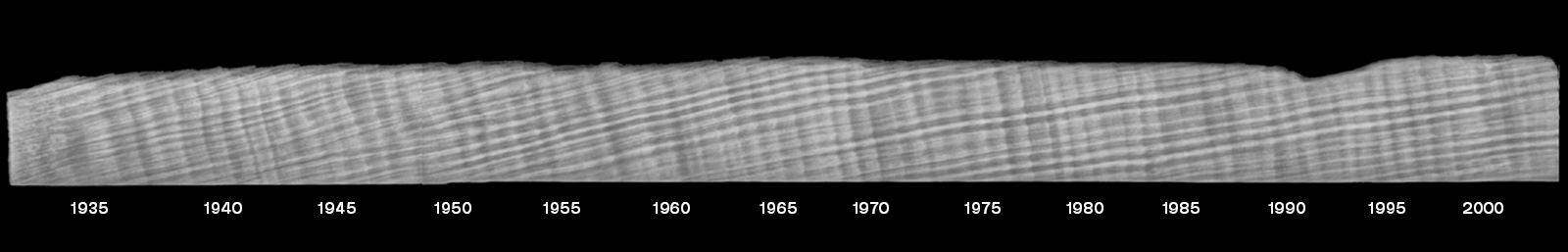

After hours of drilling, they patched the hole and swam the 6-foot-long core to the surface. Back at the lab, they split open the core samples and x-rayed them. “They’re like trees,” Wagner said. “You can count the tree rings and go back in time. Corals produce these annual bands.”

Each year the living coral organism lays down a new growth band, using the nutrients and minerals it draws from the seawater. Essentially, whatever is in the ocean water makes it into that year’s layer of coral skeleton. “So we have this long record of these tiny, tiny time capsules that kind of lock in the ocean chemistry,” Wagner said.

Using a high-tech version of a dentist’s drill, Wagner and her colleague Kristine DeLong, a professor at Louisiana State University, collect a tiny bit of dust from each growth band. Then, like detectives, they analyzed different elements in the dust for clues, looking at the variations in the coral core over time.

Jesse Nichols / Grist

Just like humans, corals build their skeletons from calcium. But sometimes they make mistakes and accidentally grab similar elements from the sea water. One of those elements is barium, which is often used as a lubricant in offshore oil wells. During the energy crisis of the 1970s, oil drilling boomed in the Gulf of Mexico. And Wagner and DeLong could see that the increase in barium levels was reflected in the coral: When oil prices crashed, production dropped, and so did the barium.

There are many other histories that scientists can see etched into this coral core. By looking at nitrogen, they can see the rise of fertilizer pollution from the Mississippi River. By looking at radioactive carbon, they can see the rise of nuclear weapons testing during the Cold War.

And the corals even tell the story of how fossil fuels are changing the climate—in the words of one scientist, “recording their own demise.” To see how, it is important to know that carbon atoms are not all exactly alike. They actually come in a few different weights depending on the number of neutrons in each carbon atom. A carbon atom with seven neutrons is called “heavy carbon”, while an atom with six neutrons is called “light carbon”. Plants prefer to use the light carbon for photosynthesis. So, inside a plant, the carbon atoms tend to be a little lighter than those, say, inside a volcano.

Fossil fuels come from ancient plants, which are full of light carbon. As fossil fuel emissions increase, the carbon atoms in our atmosphere are slowly getting lighter.

Courtesy of Kristine DeLong

You can see the same trend playing out in the corals: The carbon in the coral is slowly getting lighter in the tire samples as the world burns more fossil fuels. As those fossil fuel emissions warm the climate, they put reefs around the world at risk.

Today, the Flower Garden Benches still hold, but they will not be safe forever. As early as 2040, the Blomtuinbanken could begin to see large bleaching events every summer. If we can reduce our emissions at a more reasonable pace, climate models say we might be able to buy an extra 15 to 20 years for the Garden Banks — essentially doubling its lifespan. That window will be critical for the sanctuary’s staff and independent scientists working hard to study and protect what could become one of the last coral reefs.

“Going to a place like Flower Gardens is like — these corals, they’re still pretty healthy,” DeLong said. “Being able to manage those reefs and take care of them is important because they may be the last we have.”

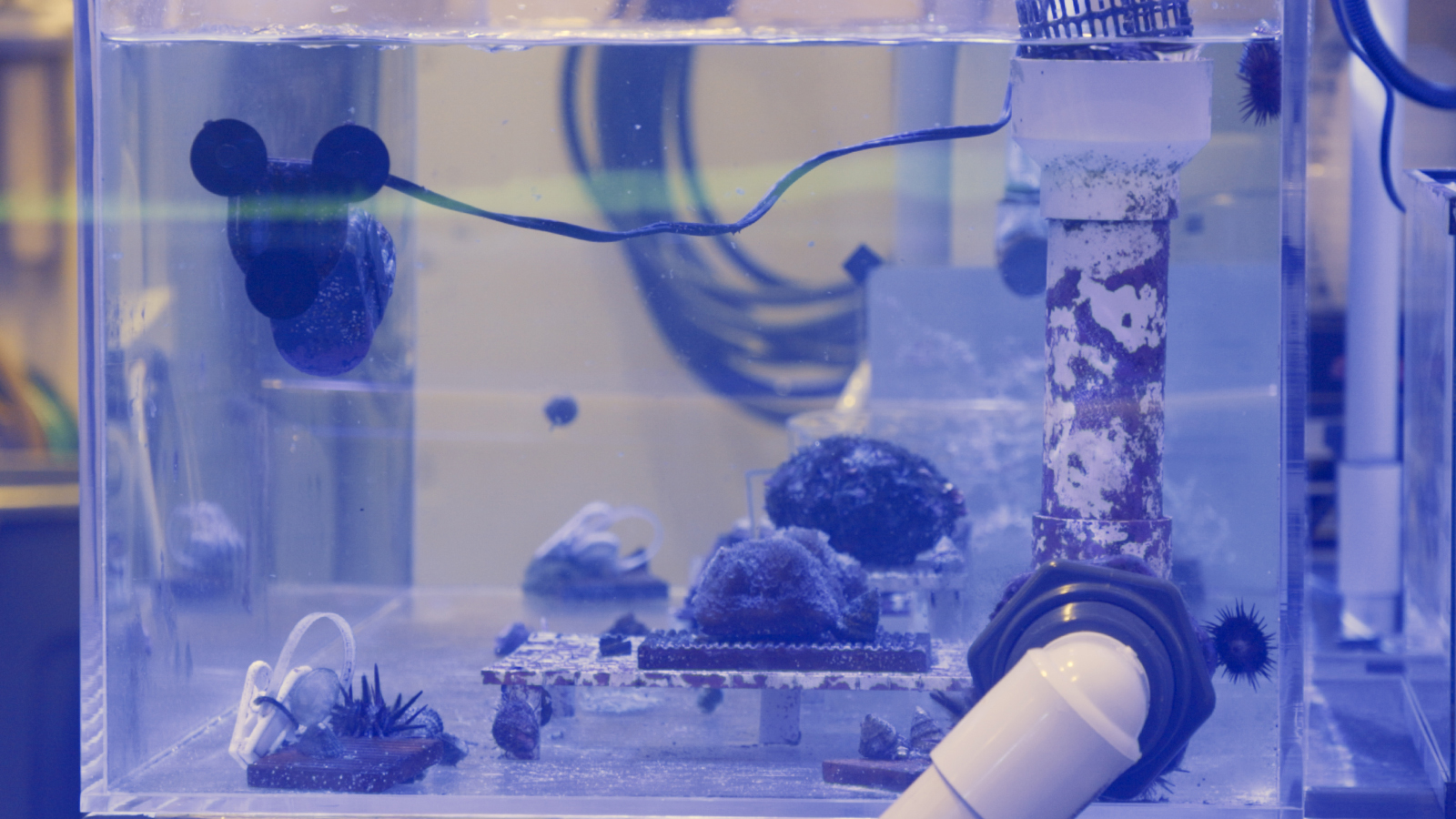

Recently, scientists at the Flower Garden Banks began collecting corals from the reef and storing them in a coral laboratory on shore. The hope is to eventually bank enough coral here in case the worst happens.

Jesse Nichols / Grist

“It’s a grim prospect,” Johnston said. “It is better to be proactive and assert certain things than to get into the situation where all the corals are bleached and dead and we have nothing left. It is my hope that nature can figure things out and adjust things. I think the problem is that the climate is changing fast enough that there may not be time.”

The Flower Banks are a product of 10,000 years of slow, steady growth, capturing annual snapshots of our world, in tiny millimeter-sized chapters. The next few decades will be critical in determining how much longer this reef can continue its ancient undersea story.