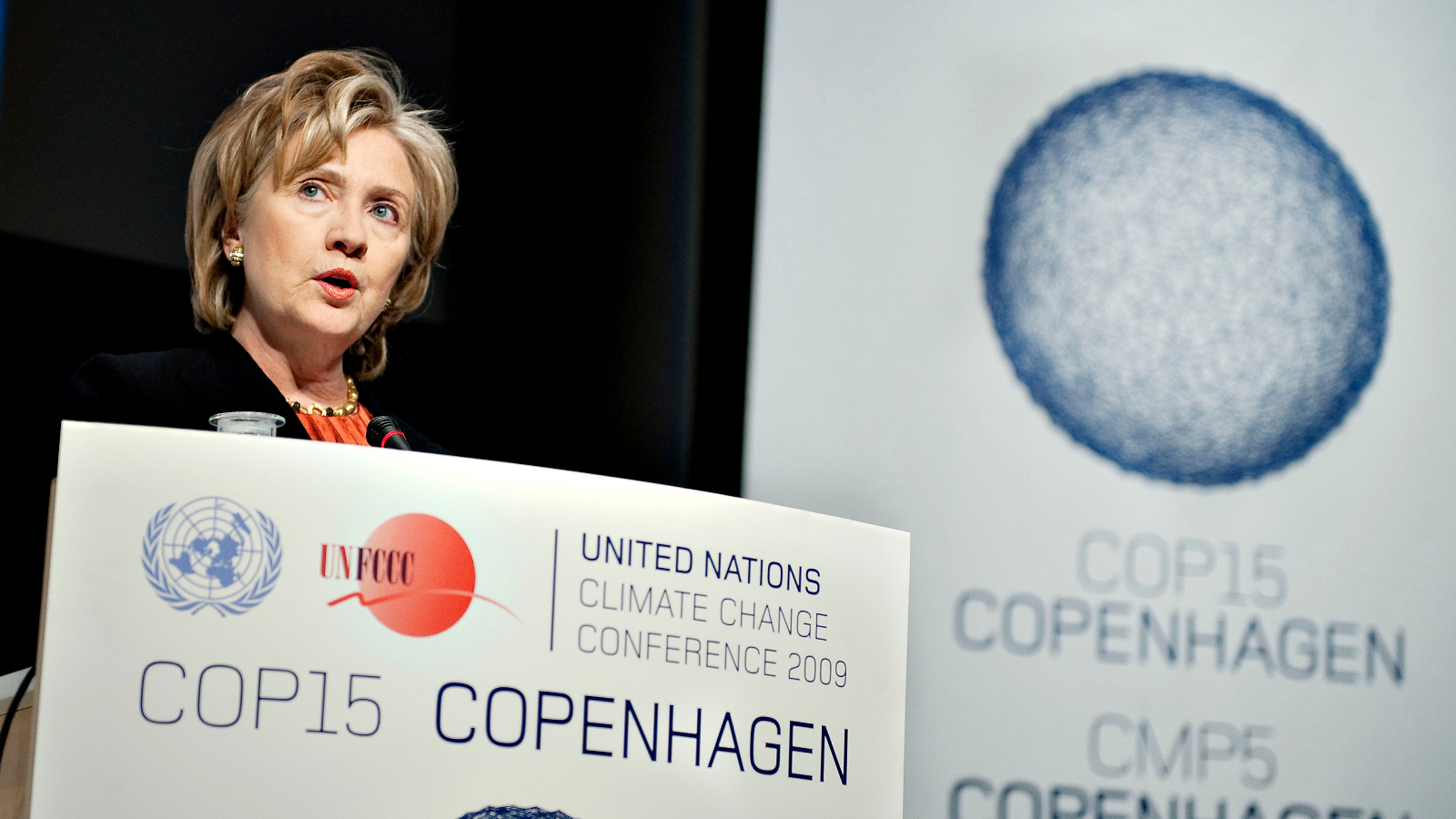

International climate negotiations are long overdue haunted by a broken promise. In the wake of collapsed negotiations at the United Nations climate conference in Copenhagen in 2009, wealthy nations, led by the United States, pledged to provide developing countries with $100 billion in annual climate-related aid by 2020. The money was intended in part to ease tensions between the rich countries that have historically contributed the most to climate change and the poorer nations that suffer disproportionately from the effects of a warming planet. But rich countries failed to meet the target in both 2020 and 2021, deepening mistrust and stalling progress at the annual United Nations climate conferences, known by the acronym COP.

A new report from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, confirms what the international organization began to suspect just before last year’s COP28: that rich nations have finally surpassed the $100 billion goal in 2022. And while they were two years late in meeting their to keep that promise, rich countries have partially offset their earlier deficits, contributing nearly $116 billion in climate aid to developing countries in 2022, according to the latest available data. That additional funding helps fill the roughly $27 billion gap resulting from rich countries’ failure to meet the $100 billion threshold in each of the two previous years.

“If you’ve underperformed in the first two years, overperforming in the rest of the period is a good way to make up for it, to make amends,” says Joe Thwaites, an expert on climate finance at the Natural Resources Defense Council. , a US-based environmental non-profit organization.

However, even $100 billion is far below the developing world’s estimated need. United Nations-supported research projects that developing countries (excluding China) will need an eye-watering $2.4 trillion a year by 2030 to move away from fossil fuels and adapt to climate change.

There also remain serious questions about the quality and accounting of the existing funding. According to the OECD report, more than two-thirds of public finance in 2022 was provided in the form of loans rather than untied grants. This means developing countries have to pay the money back, often with interest at market rates. A recent Reuters investigation also found that some aid providers required recipients to work with companies in donor countries, meaning that much of the aid money ended up finding its way back to rich nations.

Such findings are likely to inform talks next week as climate negotiators meet in Bonn, Germany in preparation for COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, at the end of the year. Negotiators must agree on a new collective goal for climate aid this year to developing countries. So far, different countries have submitted a range of proposals, with some countries floating $1 trillion annually as an appropriate number. Rich countries also want to expand their ranks so that some relatively rich countries that are technically classified as “developing”, such as the oil-rich states of the Persian Gulf, can contribute funds to the cause. Historically, only countries designated as “developed” by the United Nations in the 1990s were on the hook.

The new OECD report’s findings could be beneficial to rich nations as they negotiate these thorny issues, according to Thwaites. “Developed countries were not necessarily fighting from a position of strength or moral high ground because they did not reach the $100 billion on time,” he said. If countries continue to provide a similar level of funding for the next few years, they can make up the shortfall. “To make up for 2020 and 2021, to achieve the goal in those two years, can help rebuild a bit of confidence,” Thwaites added.

The OECD report found that funding from all types of sources – multilateral development banks, the private sector and public financing of governments – generally grew in 2022. to a total of $21.9 billion.

The report has specific progress regarding funding for adaptation measures such as sea walls and disaster-resilient infrastructure, an often overlooked area of climate finance. In 2021, countries pledged to double adaptation financing from the $19 billion provided in 2019 to $38 billion by 2025. According to the OECD report, adaptation funding had already risen to $32.4 billion one year after the pledge.

As in previous years, loans continued to make up the bulk of the financing. While developing countries have called on rich nations to move away from loans as the primary form of aid, all parties seem to agree that loans may be appropriate in some circumstances. For projects that generate income – such as investments in renewable energy – loans tend not to have a detrimental effect because they pay for themselves. But for measures that do not generate income – particularly adaptation measures such as sea walls – loans can trap countries in cycles of debt. As a result, the call for increasing grant-based funding has grown louder in recent years.

“Many countries are in debt distress,” Thwaites said. “And if they take out more loans for adaptation, where it doesn’t necessarily generate a return on the investment, that’s a challenge.”

Editor’s note: The Natural Resources Defense Council is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers play no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.