Predicting the future has always been a difficult, sometimes fruitless task, but scientists are surprisingly good at predicting how hot the year ahead will be. For decades, their models largely agreed with global temperatures. Then 2023 arrived.

At the start of the year, climate scientists at four organizations – Berkeley Earth, NASA, the UK Met Office and Carbon Brief – predicted that 2023 would be slightly warmer than the year before, with the consensus falling around. 1.2 degrees Celsius of warming (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial temperatures. But it blew past those projections to become the hottest year on recordreach an estimated 1.5 C (2.7 F). “We were really far off, and we don’t know why,” said Zeke Hausfather, one of the scientists at Berkeley Earth who worked on the predictions.

The first sign that something was amiss came in March 2023, then the world’s oceans have risen to the hottest temperatures seen in modern history. Then came the heat for the country too. This led to the hottest June on record, followed by the hottest July, and the hottest every month since. On Wednesday, the European Union’s Copernicus climate change service confirmed that last month was the hottest May on record, setting record-shattering global temperatures for one year straight, averaging 1.63 degrees C over pre-industrial times. The report is with World Meteorological Organization updated forecast that one of the next five years is likely to beat 2023 as the hottest year on record.

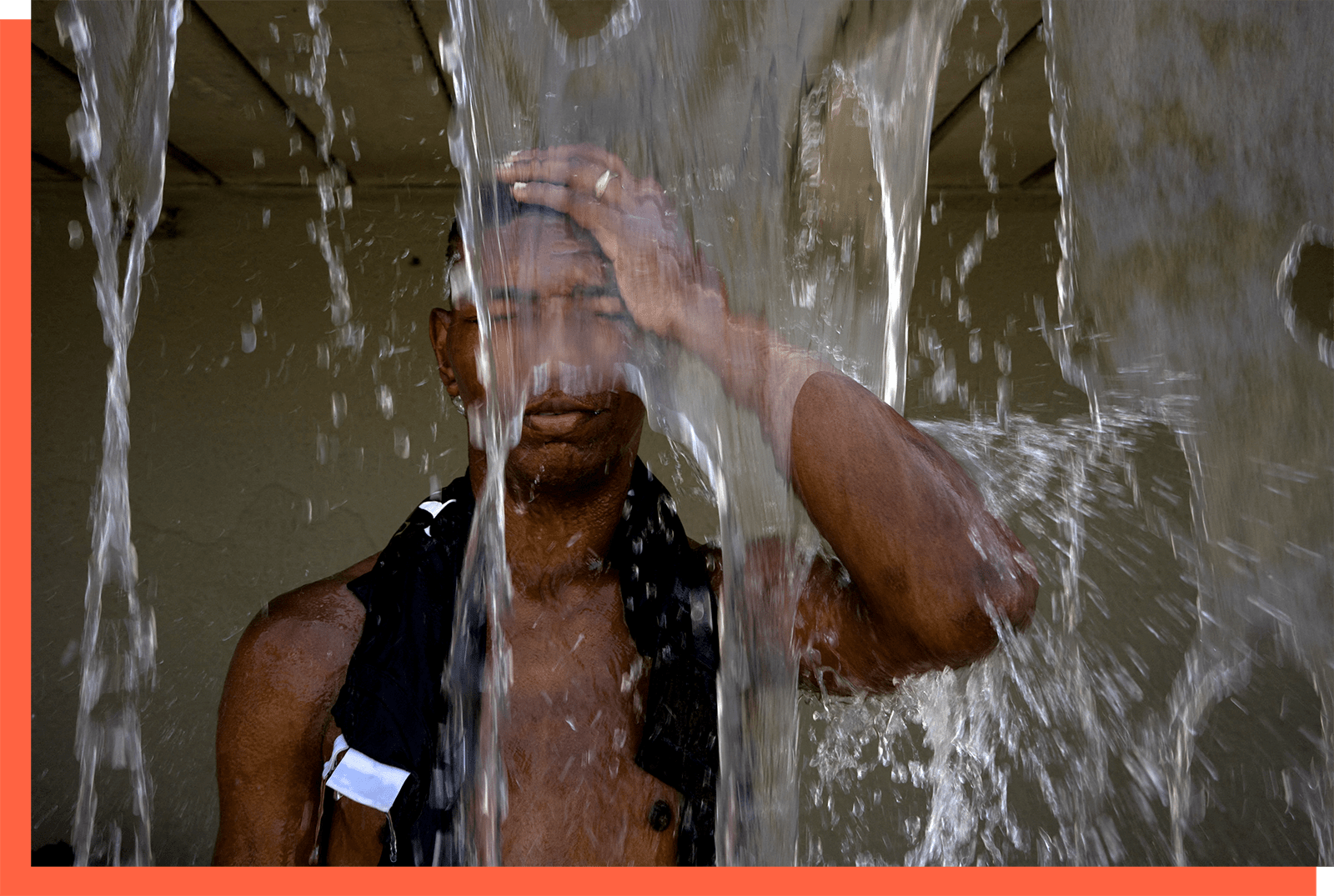

The two reports came as a heat wave swept through the western US, with 29 million Americans under heat warnings and advisories from Wednesday into the weekend. “If we choose to continue to add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, then 2023/4 will soon look like a cool year,” Samantha Burgess, director of the Copernicus Climate Change Service, said in a statement.

Much of this warming in recent years is well within the range of what scientists have long predicted would result from burning fossil fuels with abandon. The heat grew even greater when a recurring climate pattern known as El Niño took hold last summer. But scientists say these two factors alone cannot account for the rising temperatures the world has seen recently, especially in the second half of 2023. Was that extra warming a blip they can brush off, explained away by natural variability or random coincidence happenings? or was it a sign that climate change was beginning to deviate from predictable tracks?

“It’s not just an obscure quirk that nobody really cares about,” said Gavin Schmidt, the director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York. “I mean, it really matters, and it has implications for the future, how it’s resolved.” Schmidt and other scientists are exploring different theories that could explain the increased temperatures, from a reduction in global aerosol pollution to underwater volcanic explosions. “Everything is on the table,” he said.

Here’s what scientists know so far: Climate change has warmed the planet 1.3 degrees C compared to pre-industrial times. But the past 12 months have been around 1.6 degrees C warmer, according to the latest data. Some of that heat — about 0.1 or 0.2 degrees C — can be attributed to El Niño warming the Pacific Ocean. That leaves as much as 0.2C inexplicable.

Scientists have a solid explanation for perhaps 0.1 degree C of that extra heat: This could be a side effect of global efforts to reduce pollution. From January 2020, the International Maritime Organization began to a mandatory reduction of sulfur oxide emissions from marine fuel. These air particles can be harmful to human lungs, contributes to acid rain and inhibits plant growth. However, they also increase cloud cover and help reflect heat back into space. A paper published last week in Nature found that when some of these aerosol particles suddenly disappeared, the Earth began to absorb more heat.

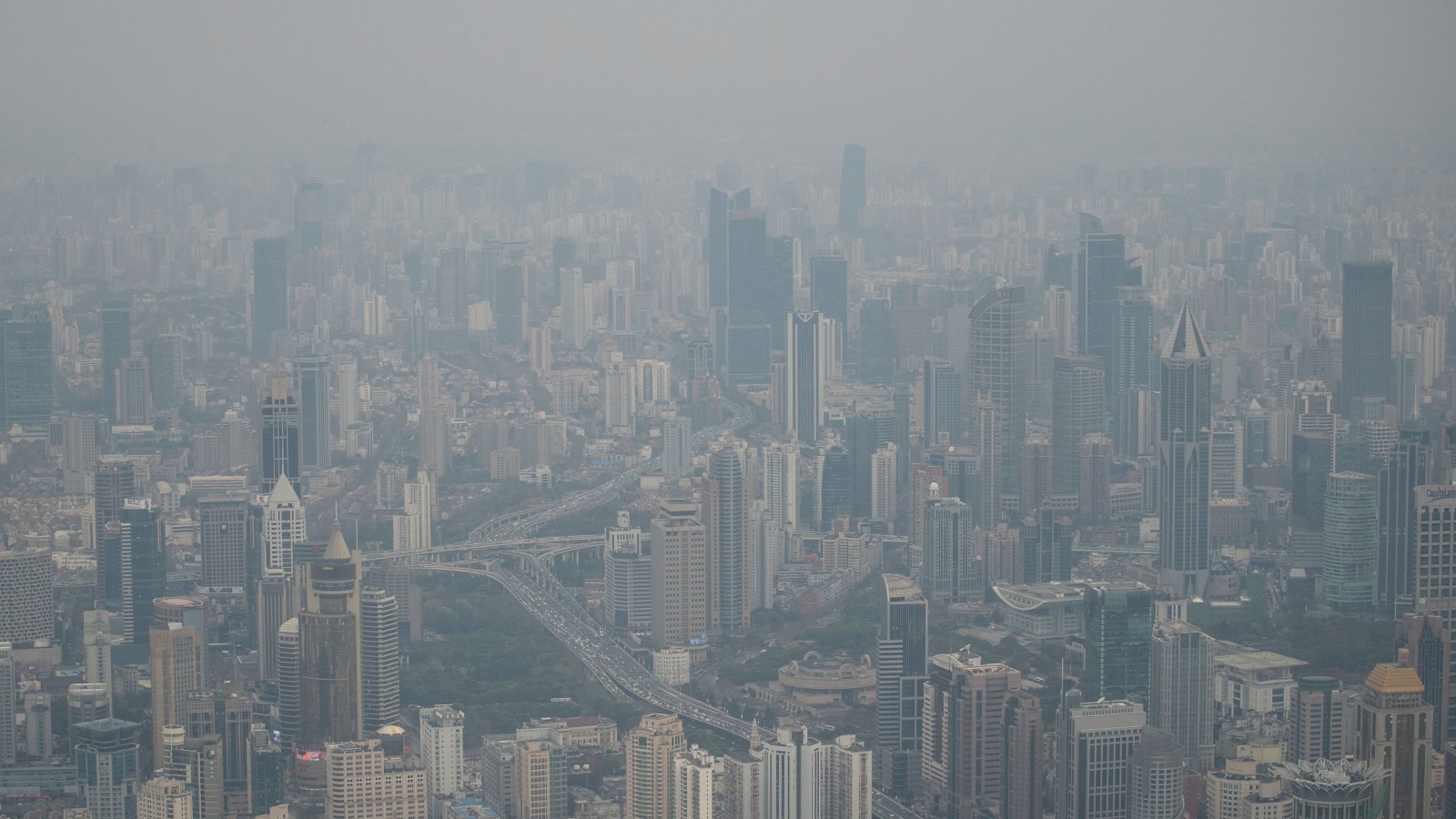

Other puzzle pieces are still being sought. A volcanic eruption in 2022 might added warmth by sending a large quantity heat traps water vapor the atmosphere inside. Changing weather patterns may have limited the Saharan sands that normally voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, allowing more sunlight to heat seawater. An upturn in solar activity may have begun sooner than expected, which traps radiation within the atmosphere. Or, maybe China was to clean up its air pollution faster than expectedand there are even fewer aerosols that reflect heat off the planet.

More ominously, some scientists argue that the planet is more sensitive to climate change than previously thought. “The climate system is an angry beast, and we poke it with sticks,” geochemist Wallace Broecker, who died in 2019, often said. Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, thinks it may be time to update that metaphor. “We’re getting closer to the beast, and we’re exacerbating it with ever greater frequency and magnitude,” he said. “So at some point there could be surprises out there.”

According to Swain, solar activity and other suspects are unlikely explanations for the “wild card” that caused so much warming in 2023. He wonders if it is even possible to solve the puzzle. Schmidt, on the other hand, hopes scientists will have solved the X factor by the end of this year.

Even as this year’s temperatures continue to shatter records, scientists were less surprised than they were in 2023. The last few months of heat align more closely with what they expected from El Niño. And this summer, El Niño’s twin, a cooling pattern called La Niña, is expected to take over. If temperatures don’t fall as predicted two or three months from now, Hausfather said, “I think that’s an indication that you know something is happening that we don’t expect and don’t really have a good explanation for.”